This year Alexander Lukashenko celebrated his 30th anniversary in power. On 10 July 1994, he won his first presidential election in Belarus. Taking into account the referendums of 1995 and 1996, which actually cancelled the separation of powers, Belarus has been under the leadership of a permanent president for thirty years.

It is noteworthy that it was in the year of his thirtieth anniversary that Lukashenko said that he was preparing the population for his departure from the post of the head of state: ‘Everybody thinks so: 30 years is a lot, it’s crazy. There are only a few people who have been working for 30 years. And people have got used to it: here he is and no one else. This is wrong. I am preparing people for this (leaving the post of president): I don’t want there to be any disappointment or failure’.

It should be said that it’s not the first time Alexander Lukashenko talks about the possibility of his resignation from the presidency. For example, back in 2019, he mentioned that he would not hold on to power with ‘blue fingers.’ In April this year, he said that he would leave his post only if the people asked him to do so, and there would be a worthy successor who would not betray him. This time his words, uttered in a recent interview, where he once again touched upon the topic of his possible resignation from the post of the head of state, raised many questions and heated discussion.

Of course, only time will show how seriously he takes the topic of his resignation and how it will affect the future of Belarus. But the fact remains that Lukashenko’s words have once again apalled not only the public of Belarus and caused a lot of versions about the prospects of his political regime.

In this piece Ascolta analyses the current domestic political situation in Belarus, especially against the background of gradual preparations for the upcoming presidential elections, which, according to our information, may take place in February-March 2025.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

Leave to stay

Back in February 2024, after voting for local authorities and the lower house of parliament, Alexander Lukashenko firmly stated that he would run for the 2025 presidential election.

‘I will go, I will go, I will go. Tell them I will go!’ – Lukashenko said, addressing the words to representatives of the Belarusian opposition. ‘And the more difficult the situation will be, the more active they will stir up our society and you among others, the more they will stress you, me and the society more, the faster I will go to these elections. Don’t worry, we’ll do it the way it’s necessary for Belarus,’ he said. Lukashenko stressed that ‘no man, a responsible president, will not abandon his people, who followed him into battle.’

In April, he said that he would leave his post only if the people asked him to do so, while there would be a worthy successor, who would not betray him. Actually, the topic of Lukashenko’s ‘worthy successor’ has surfaced earlier. In May 2023, when the number one topic was the health of the Belarusian leader, it was even discussed that in case of his death the speaker of the upper house of parliament – the Council of the Republic Natalia Kochanova would perform his duties until the new elections. However, no one seriously discussed her candidacy.

In countries where the succession of power is not envisaged by definition, the only way to ensure continuity is to appoint a successor in advance. In this sense, remembering the Turkmen transit of power, where Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov actually handed over power to his son Serdar, but then played it back, the ideal option would be Lukashenko’s eldest son Viktor, who is now a member of the Security Council of the Republic of Belarus. But Lukashenko is unlikely to go for such an option. The figure of acting Prime Minister Roman Golovchenko, who has a good reputation in Moscow, previously headed the Military-Industrial Committee, so he is not a stranger to the security forces, and also has connections in the East – he was ambassador to the UAE, was mentioned as a protégé of Moscow. Local experts were also talking about the candidacy of someone from the security forces.

In general, Lukashenko’s relations with the elite (mostly civil servants) were based on personal loyalty of officials, heads of state enterprises and law enforcers. In return, they were provided with a relatively stable and rich life. Personnel policy and social lifts for the elite were entirely in the hands of the president – he regularly reshuffled and reappointed officials to various positions, down to the district level. In general, this policy has ensured the loyalty of the elites. A recent Ascolta piece offers a more detailed analysis of Alexander Lukashenko’s inner circle and the formed main groups of influence.

But it is difficult to predict how these elites will behave in case Alexander Lukashenko appoints a successor. Perhaps, such a statement may become a reason for them to reduce their loyalty to him and look for a new patron to whom they can swear allegiance. If a successor is publicly announced, Lukashenko himself turns into what is called in American political slang a ‘lame duck’ – a president who is finishing his term. After the U.S. presidential election in November, President Biden will become such a ‘lame duck’, he will be extracting the last months, because in January the power will have to change. Lukashenko may find himself in this position, if he publicly announces: ‘I will not go to the elections. Now someone else will take my place. Lukashenko understands this very well and therefore tries not to name any specific names.

In August, as mentioned above, he started the ‘old record’ again, hinting that he might not go to the presidential election. While communicating with the residents of Gorodishche agro-township he reminded that he is not eternal, one day there will be a new leader in the country. And noted that he spoilt the citizens, but they need to get used to the idea of a change of president. However, he quickly calmed the population, promising not to abandon him ‘tomorrow, the day after tomorrow’, although ‘everything happens in life. And after his career is over, he will start a new life in some village among the people.

Another speculation about his possible departure is the bill, which Lukashenko introduced in Parliament. He proposes to add a new article to the Criminal Code. It provides punishment for violence, threat of violence, destruction or damage to property against the president, former president or members of his family. The punishment under this article is up to eight years in prison. It also provides for the introduction of liability for slander and insulting the former president.

Similar laws have been introduced before. For example, amendments to the Constitution, adopted in March 2022, included guarantees for the former president: immunity and a ban on prosecution ‘for actions committed in connection with the exercise of presidential powers’. The new initiative only added to the practice. It is clear that Lukashenko wants to secure himself for all cases of life and wants to insure himself when he will not be president but will be alive and relatively healthy. However, he understands perfectly well that it is most likely impossible to create a system that would guarantee him complete security. At one time, Kazakhstan also guaranteed the security of former President Nursultan Nazarbayev at the legislative level. But as we saw later, it did not work. The first president of Kazakhstan was stripped not only of all political influence, but even the honourable title of Yelbasy.

Lukashenko looks at all this and realises that the only guarantee of his security is to retain power for life. He hardly believes in all other guarantees: neither legislative, nor in guarantees from some successor whom he himself will appoint. Kazakhstan’s experience shows that this is very unreliable. That is why few people believe in Lukashenko’s voluntary resignation from the post of the head of state. All his life he has been showing and proving to everybody that he is of that breed of people who will hold on to the most precious thing he has – power – until the last day of his life. Therefore, there may be several subtexts in all his statements, where he hints at his possible departure.

One of them is the state of his health. No one knows his actual state of health. Ascolta sources say that recently the Belarusian president has aggravated diabetes mellitus, which, in turn, leads to exacerbation of other chronic diseases. It seems that Lukashenko’s noticeable weight gain, puffiness and permanent fatigue are associated with it. However, there is no confirmation of this information. Certainly, in this context it may happen that purely for physical reasons he will have to step aside. Or, for example, to leave halfway, remaining chairman of the All-Belarusian People’s Assembly (ANA). Recall that in April Lukashenko was elected chairman of the All-Belarusian People’s Assembly, a body of power that determines strategic directions of development of society and the state and ensures ‘inviolability of the constitutional system, continuity of generations and civil accord.

Following the referendum on constitutional amendments held in February 2022, the SNC became a constitutional body and its rights were expanded. The chairmanship of the All-Union National Tax Service can be considered as a scenario of Lukashenko’s ‘soft exit’, who, even if he ceases to be president, will retain some of his powers and control over the political situation in the country. Some experts see Lukashenko’s words as a game of coquetry. On the one hand, he hints that he may leave and one should get used to a new president. On the other hand, he would like the people and his inner circle to start asking him to stay.

As DW notes, referring to Pavel Matsukevich, senior researcher at the Centre for New Ideas, ex-diplomat: ‘Autocrats like Lukashenko often make statements in the style of such false coquetry, saying, I don’t know, I haven’t decided yet. I think that a more pleasant form for Lukashenko to announce his participation in the elections would be if he was conditionally ‘asked by the people’. It is possible that Lukashenko’s uncertainty about participating in the presidential campaign may be an attempt to attract attention and a tactical ploy. ‘The first thing that comes to my mind is that he is just trying to draw attention to himself. It would be boring if he said everything right away. Perhaps it’s being done to maintain the intrigue. Besides, then everyone would start preparing for it – so delaying the announcement could be such a tactical trick,’ says Roza Turarbekova, an Honorary Fellow at the Institute for Global Sustainable Development at the University of Warwick.

There is another ‘trick. Perhaps by making such statements, Lukashenko wants to see how his entourage reacts. In this way, he can identify the disloyal, as they say, with all the ensuing consequences. Especially since he has recently carried out personnel purges. His recent succession of personnel decisions has affected key positions in the government and the presidential administration. It combines two seemingly opposite trends – the appointment of young and active but unconditionally loyal technocrats to key positions and the return of proven but forgotten heavyweights from the past.

One of the most notable appointments is the change of the foreign minister. Lukashenko was not satisfied with the style and results of Sergei Aleinik’s work. The quiet, soft and passive diplomat was sent to an honourable retirement as a senator less than two years after his appointment. This is an atypically short period of time for the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Belarus. The previous foreign ministers – Sergei Martynov and Vladimir Makei, who died at the end of 2022 – held the post for ten years each. Aleinik was replaced by Maxim Ryzhenkov, who was already a diplomat in the 2000s, but for the last eight years worked as first deputy head of the AP. According to reviews, he is more active, willful, not too compromising and undoubtedly loyal to Lukashenko. The new foreign minister, like anyone else in the post now, is unlikely to be able to squeeze anything more out of the situation Minsk finds itself in. However, Lukashenko would still like to see a person closer to himself in temperament and style at the head of the Foreign Ministry – ready to boor foreign enemies without sentimentality and dismiss all diplomats suspected of disloyalty who have been left there by oversight since 2020.

Another high-profile appointment is the transfer of the Belarusian ambassador to Russia, Dmitri Krutoy, to the post of head of the AP. Dmitri Krutoy is a bureaucratic prodigy in terms of speed of movement up the nomenclature ladder.

As noted by the well-known Belarusian political expert Artem Shreibman, the official is only 43 years old. In 2018, he became the youngest Minister of Economy in the history of Belarus, one of the brightest representatives of the liberal wing of the government. A year later, he was promoted to deputy prime minister, making him responsible for the economy and negotiations on integration with Russia. In mid-2020, Krutoy became deputy head of the AP. And two years later – ambassador to Moscow with the powers of Deputy Prime Minister, which reflects the real role of this position in the Belarusian system.

In his post in Russia, Krutoy demonstrated bureaucratic activism, atypical for Belarus. He constantly travelled to Russian regions, threatened to punish marketers of major exporters for passivity in the market of the main ally, demanded Russian media to take off the air those artists who condemned repression in Belarus, and initiated the unification of extremist lists of the two countries.

Many Belarusian officials after 2020 went from a young reformer to a reactionary statesman. But in Krutoi’s performance, this act of swearing an oath to the new course apparently seemed particularly convincing to Lukashenko, since he decided to entrust Krutoi with the management of the country’s main civil body.

Another of the most unexpected appointments was the return of Natalia Petkevich to the leadership of the country. She became Dmitri Krutoy’s first deputy in the AP. Having held various positions in Lukashenko’s administration in the 2000s, Petkevich was a real grey cardinal in the then Belarus. She is remembered as a reactionary in her views, tough and impulsive boss, in other words, a person similar in management style to Lukashenko himself. For the last 10 years she was in the shadow, not holding public office, but she was decided to return to the ranks. It is clear that Lukashenko has a short bench and has to turn to proven personnel from the past.

Another veteran of the Belarusian official politics – Alexander Kosinets – has recently made a similar kambek. The 65-year-old former head of the presidential administration was brought back from retirement in April to be appointed Lukashenko’s deputy in the new constitutional body – the All-Belarusian People’s Assembly. Such personnel reshuffles rather indicate that Lukashenko is more likely to go to the polls, refreshing his regime’s cadre.

In any case, whether Lukashenko will run himself or will suddenly risk a scenario with a successor, he needs to maintain a complex political image, which includes allied relations with Russia and peacemaking. However, there is also a point of view that Lukashenko is only broadcasting signals sent from Moscow. It is difficult to agree with this version. Probably, we should not deny Lukashenko’s subjectivity: as experts note, he has vast experience of foreign policy manoeuvring, which became complicated after the West’s non-recognition of the 2020 election results, but has not stopped completely. Yes, after 2020 Lukashenko became very close to Russia, which unambiguously supports him, but on occasion he does not miss an opportunity to make it clear that despite his friendship with the Kremlin, he has his own political interests. By the way, the promise to leave was accompanied by parallel statements that only Lukashenko can preserve peace and stability in Belarus.

Peacemaker

One of the key arguments of Alexander Lukashenko in favour of preserving his political regime is that it ensures peaceful development of the country and prevents it from being dragged into war. That is why Lukashenko’s statements today about the need for peace talks between Moscow and Kiev, after the raid of the Ukrainian Armed Forces in Kursk region, are in sharp contrast to the position of the Kremlin, which says that there will be no negotiations with Ukraine. If Lukashenko says: ‘Let’s sit down at the negotiating table and put an end to this fight. “Neither the Ukrainian people, nor the Russians, nor the Belarusians need this,” he continued in the interview. At the same time, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that Putin ‘clearly said that negotiations with Kiev after the invasion of Kursk region are out of the question.’ Then how should Lukashenko’s words be understood? Are they a challenge to the Kremlin, following the Chinese ‘methodology’ about the need to hold peace talks as soon as possible, or peaceful rhetoric for domestic consumption?

Firstly, as we have already noted, Lukashenko has retained a certain degree of subjectivity in his relations with Moscow and can broadcast things that may even seem oppositional to the Kremlin. Negotiations from Russia’s point of view is a surrender of Ukraine, but from Lukashenko’s point of view it is something that would stop the processes that threaten him personally. Lukashenko remains a loyal ally of Russia and will not go anywhere from its influence. However, he does not want to lose his power. This could happen if Russia absorbs Belarus, or if Putin is defeated in the war with Ukraine. Therefore, the best type is the image of a peacemaker.

On 17 August, at the summit ‘Voice of the Global South’, to which he was invited by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, he once again confirmed that Belarus is ready to make peace initiatives and provide a platform for negotiations on conflict resolution. Lukashenka’s peace initiatives came against the backdrop of a series of military and political events. In June, the Belarusian authorities deployed army units to the border with Ukraine to strengthen its protection. At that time, Minsk officials said about the possibility of an attack from Ukraine. However, on 13 July, the Belarusian leadership ordered to withdraw the troops. According to Lukashenko, the situation has normalised, the Ukrainians are withdrawing their troops, so we can do the same – return soldiers and equipment to the places of permanent deployment. He even noted the positive role of the Ukrainian military in defusing tension.

But August came and there was a Ukrainian invasion of the Kursk region. There were outraged voices in Russia that our ally had in some way contributed to this and had ‘played along’ with Ukraine. In particular, thanks to its peacekeeping actions, the enemy was able to release certain forces and direct them towards the Kursk area. Against the background of all this, Alexander Lukashenko convened another meeting, where he announced that some drones had invaded the territory of Belarus, all of them were shot down. However, the conclusion is as follows: Kiev does not want peace, has again gone for aggravation. So the troops will have to go back to the border, which was done. Although Minsk still intends to sort out what happened there in reality.

In turn, Ukraine reported that the situation in the area is calm and there is nothing to fear. This apparently means that Kiev does not believe in an attack from Belarus. Or, at least, they say so publicly, as if hinting that Lukashenko is unlikely to go for a serious escalation. And all these relatively threatening statements of his are a reaction to reproaches from Moscow. In addition, there were various versions that the current Belarusian leader is trying to establish relations with the West to some extent on the eve of the next presidential election. By the way, Belarus’ strategic partner and friend China is worried about the prospect of blocking the transit of its goods to Europe. Poland has hinted at this many times in response to the so-called migration attacks from the Belarusian side. Besides, there are big doubts that comrade Xi Jinping will be very happy if Belarus enters the war. At least because in this case it will be very difficult to carry out uninterrupted supplies of goods.

So Alexander Grigorievich has to manoeuvre. It is not so easy for him. And no matter how strange it may sound for Moscow, Belarus also has its own interests, which do not always overlap with the aspirations and objectives of its older brother. And Lukashenko’s peacekeeping initiatives speak eloquently about it. Although the space for peace initiatives still exists, but even compared to July it has narrowed considerably when Lukashenko once again spoke about peacekeeping and Viktor Orban came to Moscow. By the way, before that, in late May, Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto visited Minsk.

An unsuccessful attempt

Some of the experts perceived Lukashenko’s peaceful gestures, among other things, as an attempt to flirt with the West. Back in 2022, when Russia’s military successes were, to put it mildly, not brilliant, Minsk could not help but think about the consequences of Russia’s defeat. Lukashenko began to look for a saving ‘straw’. These were probably the reasons for the intensification of attempts to establish a dialogue with the West. The problem in the relationship between the West and Belarus was political prisoners.

In early September 2022, Lukashenka started talking about a large-scale amnesty and possible pardon of some prisoners. Two weeks later, Lukashenka unexpectedly pardoned three political prisoners, including the well-known journalist of Radio Liberty Oleg Gruzdilovich (according to unofficial information, his release was the result of secret negotiations between Minsk and Washington). At the same time, the authorities made it clear that this would not be the end of the matter and the release of some of the political prisoners remains on the agenda. There were rumours that the now deceased Foreign Minister of Belarus Uladzimir Makei held a series of behind-the-scenes meetings with Western diplomats on the margins of the UN General Assembly session in New York.

According to Sviatlana Tihanouskaya’s senior adviser Franak Viachorka, during these meetings the Belarusian minister suggested the West to ‘turn the page’. Makei seemed to hint that Lukashenka should be saved from Russia now, otherwise Belarus could hold the same ‘referendums’ as in the occupied territories of Ukraine. He asked to lift sanctions on the potash industry and promised to gradually release political prisoners if Minsk was not pressurised. Western diplomats and politicians did not comment on the information about the behind-the-scenes talks. While official Minsk made timid attempts to negotiate with the West, the Kremlin sharply raised the stakes in its war with Ukraine. Russia announced mobilisation, held pseudo-referendums in the occupied territories and formalised their annexation. Such escalation, according to experts, put Belarus in danger of directly entering the war. Lukashenka again began to have ‘political convulsions’ and in the end he was forced to demonstrate his loyalty to Lukashenko’s ‘big brother’ by directly stating that ‘Belarus is participating in a “special military operation in Ukraine”. But at the same time he emphasised that ‘we are not killing anyone’ and ‘we are not sending our military anywhere’. And the role of Belarus in the ‘special operation’ is allegedly to ensure that no one shoots ‘in the back of the Russians’.

On the one hand, Lukashenko would like to reduce his dependence on Moscow. However, a separate agreement with the West required serious concessions: the release of political prisoners (if not all, then most of them) and a complete withdrawal from Putin’s ‘special operation’. Lukashenko realises that Russia’s defeat in this war is not in his interests. If military defeat leads to a serious weakening or even collapse of Putin’s system, then in that case his own regime will be left without any support, alone with both the West and the Belarusian people. In fact, Lukashenko found himself in a classic zugzwang: any move now worsens his position. But supporting the Kremlin’s escalation course seems to be a more acceptable option for him than an open conflict with Putin.

In the West, Belarus is often perceived as a satellite deliberately chained to Russia. And the reasons for this are understandable. Vladimir Putin meets with Alexander Lukashenko more often than most top Russian officials. The Russian army freely uses the Belarusian territory and military infrastructure for its needs. Russian tactical nuclear weapons (or at least their components) have been stationed in Belarus since the summer of 2023. Two-thirds of Belarusian merchandise exports go to Russia, and a significant part of the remaining one-third depends on Russian logistics. Minsk is a member of all post-Soviet integration alliances. Russia pays for loyalty through cheap energy resources, new loans, instalments and refinancing of old debts and other forms of support.

However, a gap between the strategic interests of Minsk and Moscow still exists. The basic need of any authoritarian regime, including the Belarusian one, is the preservation of sovereignty. And the Russian authorities clearly consider the independence of Belarus and Ukraine a historical mistake. The distance between the interests of Minsk and Moscow may change depending on the regional context and the economic situation in both countries. The ground for new contradictions may become, for example, a decrease in Moscow’s ability or willingness to financially provide Belarus with the same volumes as it does now. This mismatch of ‘supply and demand’ in this pair has been the cause of many conflicts since the early 2000s.

Minsk’s close dependence on Moscow obviously reduces the potential for the West’s direct influence on the Belarusian authorities. However, Lukashenko himself has recently tried to signal the West with the necessary force. The Belarusian authorities introduced a temporary visa-free regime for citizens of 35 European countries from 19 July to the end of 2024. The list includes more than twenty member states of the European Union, which has imposed a very extensive list of sanctions against Minsk. Experts believe that by doing so, the Belarusian side is trying to force its opponents to at least think about replacing the current confrontation with dialogue.

The list of countries, published on the website of the Foreign Ministry, includes members of the European Union – from France and Germany to Estonia and Romania – as well as such European countries as Great Britain, Switzerland and Iceland. The Foreign Ministry website says that the decision was taken ‘to further demonstrate openness and peacefulness, commitment to the principles of good neighbourliness, as well as to facilitate inter-human contacts and improve freedom of movement,’ while it was supported by President Alexander Lukashenko. Earlier – back in 2022 – the Belarusian authorities introduced a visa-free entry procedure for citizens of the neighbouring republics – Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. It is also valid until 31 December this year and remains unchanged. Thus, the simplified entry procedure now applies to 38 European countries. The states on the list can’t be called friendly to Belarus.

It’s worth noting that the relationship deteriorated sharply in 2020, when the presidential elections were held in the republic, causing unprecedented protests. They were harshly suppressed, and opposition leaders such as Maria Kolesnikova, Viktor Babariko and Sergei Tikhanovsky were arrested and then sentenced to prison terms of varying lengths, but not less than ten years. After the protest wave subsided, Belarusian law enforcers began to methodically and scrupulously search for, find and punish political activists and protesters in general, which provoked the departure of hundreds of thousands of Belarusians from the country. Emigration continues even now.

The European Union did not recognise the results of the 2020 presidential election and began to gradually impose sanctions. After the Russian troops entered the territory of Ukraine in 2022 – the Russian military came in, including from Belarus – the number of various restrictive measures exceeded 1 thousand. In fact, Minsk’s relations with the EU are in the confrontation mode. Recently, the Baltic States – Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia – decided not to allow cars with Belarusian licence plates to enter their territory. Against this background, the visa relaxation looks like an unexpected step. It is noteworthy that this is not the first step of the Belarusian authorities, which is addressed to the West and looks like a conciliatory gesture. On 2 July, Alexander Lukashenko announced that soon ‘very seriously ill people, who did not manage to escape and are in places not so remote, who broke and ruined the country in 2020,’ would be released from Belarusian prisons.

A few days later, about a dozen prisoners were indeed free. Among those whose names were mentioned was a veteran of Belarusian politics, cancer patient Grigory Kastusev, sentenced to ten years in prison in 2022. Of course, these steps are unlikely to lead to any solutions, but at least for some EU countries it is a clue to start talking about the possibility of adjusting relations. However, the EU did not appreciate the Belarusian goodwill gestures. The EU Council announced about adding 28 more citizens of Belarus to the EU sanctions list. The decision was taken in connection with ‘ongoing internal repression and human rights violations in Belarus.

Director General of the news agency BelTA Irina Akulovich, head of the press service of the President of Belarus Dmitri Zhuk, head of the Main Department for Combating Organised Crime and Corruption Andrei Ananenko, as well as his deputies Mikhail Bedunkevich and Dmitri Kovach were put on the sanctions list. Two prosecutors, three judges, several journalists and heads of colonies also fell under the restrictions. Then, the U.S. Treasury Department expanded sanctions against Belarus, including 19 individuals and 14 entities. Among the sanctioned are Belcanto Airlines and Rada Airlines, the plant ‘Legmash’ and the manufacturer of drones ‘KB Unmanned Helicopters. Shortly before that, the sanctions list was expanded by the UK to include three legal entities and four individuals.

Canada did not lag behind its partners. It imposed restrictions against six more Belarusian companies and ten individuals. Among them – the youngest son of Belarusian President Nikolai Lukashenko and Chief of the General Staff of the Belarusian Army Pavel Muraveiko. So, the West responded to Lukashenko in its own way. The German Foreign Ministry, for example, commented on Minsk’s introduction of visa-free regime as follows: ‘Not every country, where you don’t need a visa, is a good place to visit.

Probably, Lukashenko really has a desire to improve relations with the West and achieve the cancellation of sanctions or at least part of the restrictions. But without distancing himself from the Kremlin’s policy, without releasing political prisoners and curtailing mass repressions, this is impossible. Pardon or exchange of 5-10 or even several dozens of political prisoners, visa-free regime will not fundamentally change anything. Unless Lukashenko decides to take more decisive steps, the current symbolic signals and gestures will end the same way as in 2022, i.e. with nothing.

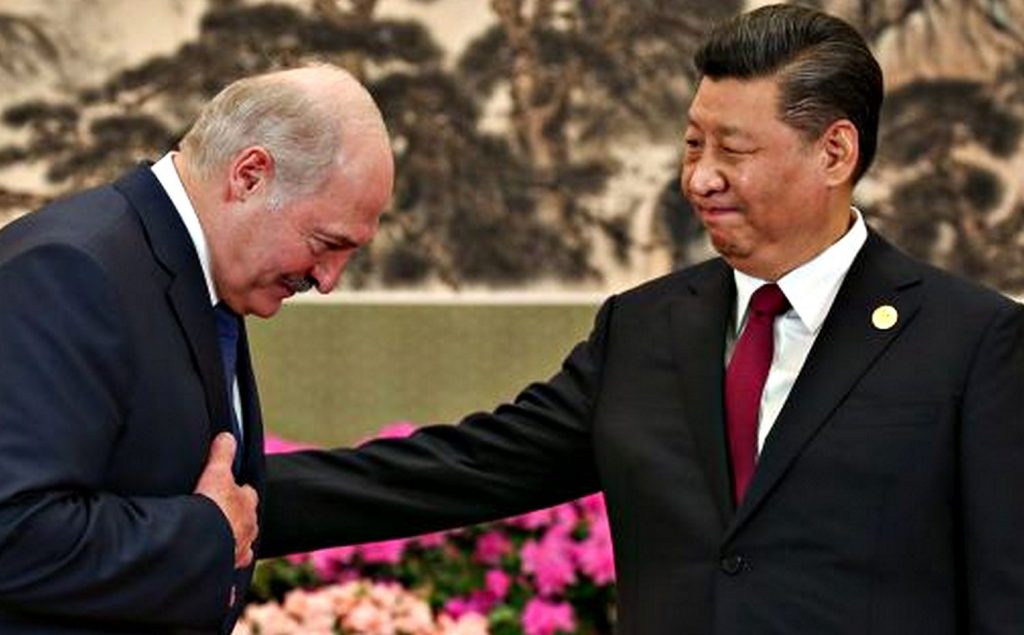

Minsk and Beijing

And if Lukashenko has no changes on the western front, as they say, things are going quite well in the eastern direction. We are talking, first of all, about the People’s Republic of China. According to the Belarusian state media, thanks to joint efforts, China and Belarus have already reached the level of all-weather strategic partnership, and mutually beneficial cooperation is steadily deepening. ‘China has been Belarus’ second largest partner for many years in a row. Last year, mutual trade grew by 67.3 per cent year-on-year. This is a great growth and a new record,’ said Li Qiang, Premier of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, who arrived in Belarus on an official visit.

The parties have signed a number of joint documents, including 17 protocols. The head of the Council of Ministers of Belarus and the head of the State Council of China signed a joint communiqué of the two governments. This document defines the key areas of cooperation, namely: increase and optimisation of trade, industrial cooperation (especially in pharmaceuticals, energy, trade in intermediate goods), technical, economic and credit assistance, scientific and technical cooperation, as well as in agriculture, culture, education and sports. In the communiqué, Minsk and Beijing condemn unilateral sanctions as a way to interfere in the internal affairs of the states.

During the meeting between Alexander Lukashenko and Li Qiang, the Belarusian leader called the visit of the Chinese premier historic and a continuation of the agreement between Lukashenko and Xi Jinping during their meeting in Astana. The deep interest in bilateral relations is evidenced by the fact that Lukashenko visited China twice in 2023. In July 20224, Belarus became a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). And just a few days after Belarus became the tenth member of the SCO, Beijing and Minsk held joint military exercises. The 11-day manoeuvres started on the eve of the NATO summit in Washington and took place five kilometres from the NATO borders.

The special nature of the relationship between Belarus and China is emphasised by the fact that Lukashenko’s youngest son Nikolai is studying in China. He is studying biotechnology at Peking University. Biotechnology is a very promising area of the Belarusian economy. It is believed to catch up with the IT-industry in terms of investment appeal. They are in demand literally everywhere: in the energy sector (various types of biofuels), in medicine (raw materials for innovative drugs and medicines of the future, production of vitamins), in agriculture (plant and animal protection, microbial fertilizers, feed additives). Earlier, Alexander Lukashenko, assessing Minsk’s interest in co-operation with Beijing in the field of biotechnology, said: ‘Here it is both personal and state.’

But the personal for Alexander Lukashenko in relations with China is not only his son. First of all, strengthening relations with Beijing is also an insurance against Russia, which can at any moment absorb Belarusian sovereignty due to the presence of a military component on the territory of Belarus or Minsk’s dependence on Moscow in economic terms. Moscow can wait for the weakening of Lukashenko’s position among the elite or otherwise ‘accelerate’ the Belarusian ruler’s departure from the political scene. Therefore, after Lukashenko lost the opportunity to build relations with the West, China remains the only guarantor of preserving Belarusian sovereignty, or, to be more precise, of preserving the sovereignty of Alexander Lukashenko personally.

Li Qiang’s visit is of course very important from the economic point of view. After the breakdown of economic ties with the West, complete dependence on Moscow is also a ruinous path for Belarus. However, Li Qiang’s visit is more political than economic. The visit of such a high-ranking Chinese official to Minsk is a mirror image of Alexander Lukashenko’s trips to China and a demonstration to the Russian leadership that Beijing is interested in the preservation of Belarusian statehood, albeit in the form of a Russian satellite. It is worth noting that Lukashenko feels quite comfortable in this model of double subordination. When on the one hand he has special relations with the Kremlin, which allow him to provide the Russian Federation with his territory as a springboard for attacking Ukraine, and on the other hand he has special relations with China, which will not allow Russia to ‘swallow’ Belarus. This demonstrates the simple manoeuvring of Alexander Grigorievich Lukashenko.