Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has declined to run for a second term as head of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party. The decision kicks off an exciting leadership race where Kishida has no clear successor yet. But talk of his controversial legacy is already in full swing.

In this article Ascolta analyses the domestic political situation in Japan against the backdrop of the incumbent prime minister’s refusal to run for a second term, as well as the country’s preparations for the next elections. In this context, the current trends and the main prospects for further development of the political crisis that has begun are studied.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

The scandalous party of the unpopular prime minister

After a week in which Japanese citizens prepared for a mega-earthquake, the biggest seismic jolt occurred in politics. At the end of next month, Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party will elect a new leader, and in recent weeks the mood in Tokyo had been swinging in one direction only: the unpopular but famously stubborn Kishida would run and win against all potential successors.

It all came crashing down suddenly, in the midst of the usually measured holiday season. Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida took the unexpected step of announcing last week that he will not run for the leadership of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in September. This means that the country will soon have a new prime minister. Kishida himself motivated his decision by the fact that the party, which has been shaken by high-profile scandals in recent months, is capable of renewal, the first step towards which will be his departure. Fumio Kishida’s decision to voluntarily withdraw from re-election for a second term as leader of the LDP, which he announced just a week before the party’s electoral committee was to name the exact date of the election for the head of this political force, came as a complete surprise to the general public.

The Liberal Democratic Party has indeed been plagued by scandal in recent years. The most sensational scandal in the political life of Japan remained the story about the links of many heavyweight politicians with an influential but highly suspicious religious group – the Unification Church. It was founded in South Korea in 1954 by preacher Moon Sung-myung (his followers are called munites after his name). Because of its questionable practices, including mass collective marriages between previously unknown sect members, many experts classify the Unification Church as a destructive and totalitarian sect. The church has changed its legal name several times, now registered as the Federation of Families for Unification and World Peace.

On 8 July 2022, Japan assassinated former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, the record holder for the longest time in office (nearly nine years in total). He had been forced to resign two years earlier due to worsening colitis, but continued his political activities and on the day of his death had travelled to the city of Nara to address a rally in support of the LDP candidate. Tetsuya Yamagami, 41, who fatally stabbed the former prime minister, told police that he wanted to take revenge on the Unification Church, which had inherited his family’s fortune. Yamagami claimed he targeted Abe because of his ties to the Unification Church. He did send congratulatory telegrams to the sect, and in September 2021, he recorded a video message to an event organised by the Federation of Families for Unification and World Peace.

The investigation launched after Yamagami’s testimony revealed the sect’s longstanding contacts not only with the family of the assassinated prime minister, but also with the entire political top brass of the country. It turned out that about half of LDP parliamentarians, including members of the government, were linked to the Munits. In an attempt to save the ruling party’s reputation, Kishida promised to sever all ties with the Unification Church and conducted a major cabinet reshuffle, resigning seven ministers suspected of collaboration with the sect, including Nobuo Kishi, the brother of the assassinated Abe, who headed the Defence Ministry. In October 2023, the Japanese government initiated a judicial procedure to dissolve the Unification Church, stripping it of its status as a religious organisation.

No sooner had the ruling Liberal Democratic Party recovered from this scandal than a new one broke out: several members of the largest faction within the LDP were found to have embezzled money while collecting political donations.

In Japan, collecting donations from individuals for party activities is quite legal, but there are, as they say, nuances. As a rule, money is raised by selling tickets to various party receptions, but each member of parliament has his or her own quota on how much proceeds from how many tickets sold (usually at 20,000 yen, or $138 each) can then go to his or her party – depending on his or her status and number of re-elections to parliament. And of course, it has happened many times that prominent members of both the LDP and other parties have ended up raising far more than the intra-party norm at fundraising events. In itself, this is not a violation of the law on control of political funds, but the most important thing was to declare the excess in time.

So for the whole year 2022 at eight fundraising events Fumio Kishida collected about 150 million yen (more than $1 million), spending about 19 million yen ($132 thousand) of them for his party needs. But he did not forget to account for the unused 87 per cent of the funds he received. Therefore, no questions were raised against him. But more than 80 LDP lawmakers somehow forgot about such reporting for several years. According to Japanese media reports, members of the two largest factions within the ruling party, the Abe and Nikai factions, defaulted on income from fundraising events totalling ¥676 million (nearly $4.5 million) and ¥265 million (more than $1.7 million) respectively between 2018 and 2022. The list of politicians implicated in the scandal includes former Japanese government secretary-general Hirokazu Matsuno, ex-economy minister Hiroshige Seko, ex-chairman of the parliamentary liaison committee Tsuyoshi Takagi and ex-LDP political council head Koichi Hagiuda.

One of the criminal cases involved Yoshitaka Ikeda, an LDP (Abe faction) lawmaker arrested by the Special Division of the Tokyo Prosecutor’s Office, who earned more than ¥48 million from kickbacks. As it became known during the investigation, upon learning of the criminal case against him, before his arrest, Mr Ikeda managed to instruct his subordinates to break an office computer with a screwdriver, which stored information about the money he received illegally.

As the corruption scandal was just beginning to unfold, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida ordered the suspension of all new party fundraising events, and announced he was resigning as head of his own Kochikai faction of the LDP to appear as a more neutral leader of the entire party. He was initially reluctant to initiate a high-profile government reshuffle, according to several media reports, deciding to wait for the verdict of the investigating authorities. But the public pressure growing day by day forced him to change his position. There has been a reshuffle in the government.

The prime minister replaced four ministers and 11 other LDP members in ministerial positions. Then the Party Discipline Commission of Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in decided to punish 39 members of parliament and other prominent LDP functionaries found guilty of financial fraud in receiving political donations. As expected, Ryu Shionoya, one of the leaders of the largest faction in the LDP, and Hiroshige Seko, former head of the LDP faction in the upper house of parliament, were subjected to the most severe punishment – deprivation of their party tickets.

Against other figures involved in the scandal, less harsh but sensitive measures were taken: suspension of party membership, revocation of party posts and withdrawal of support in elections. Kishida did not shrug off personal responsibility. The LDP leader admitted that he felt ‘a crisis of confidence in the government by the Japanese people’ and promised maximum openness in investigating all abuses. Fumio Kishida became the first sitting head of government in Japan to appear before the parliamentary ethics committee over a corruption scandal in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party.

The high-profile kickback case only added to the list of numerous scandals involving high-ranking figures of the ruling party. In mid-March, the Tokyo District Court sentenced former LDP lawmaker and former deputy justice minister Mito Kakizawa, who was found guilty of bribery and violation of election law, to two years in prison with a five-year suspended sentence. Tokyo prosecutors charged Mr Kakizawa in January this year after receiving information that he had bribed members of the local legislative assembly in last April’s elections with 200,000 yen ($1,300) each, under the guise of paying them to work on the campaign of the head of Tokyo’s Koto administrative district. After the story went public, Mito Kakizawa resigned as deputy justice minister and left the party, and last December he and four of his secretaries were arrested and prosecuted.

The conviction of Japan’s former deputy justice minister coincided with a scandal involving leaders of the LDP’s youth wing. A party event in Wakayama Prefecture resulted in a party with half-naked dancers who, after performing on stage, went down to the hall and wandered between the tables where young leaders of the ruling party were sitting, kissing them and receiving tips from them. The story took place back in November last year, but candid photos from the party only hit the press in March. As it became known to the Japanese media, the politicians and deputies who wanted a thrill passed tips to the girls in a very unusual way – from mouth to mouth.

After the disclosure of this story, the head of the LDP youth department Takashi Fujiwara was forced to leave his post, and Prime Minister Kishida, who heads the LDP, speaking at a hearing in the budget committee of the upper house of parliament, called the behaviour of the younger change of the ruling party ‘absolutely inappropriate and regrettable’.

Another scandal in Tokyo, but this time not related to financial fraud, was the deputy chairman of the ruling LDP, Taro Aso, who served as foreign minister and prime minister of Japan in different years. Speaking in Fukuoka Prefecture, Mr Aso called Japan’s current foreign minister Yoko Kamikawa a ‘new star’ for her high level of English language skills, but immediately dubbed her an ‘aunt’ and ‘not so pretty’.

‘I can’t say she is such a beauty, but she speaks boldly, and she speaks English without the help of diplomats. She made her own appointments. We used to look at her and think: ‘What an aunt!’,’ Taro Aso remarked. At the same time, he confused her name, calling her Kamikawa instead of Kamimura, and also stated that the woman had allegedly never held the post of Japan’s foreign minister before (in fact, the two women who headed the diplomatic department were Makiko Tanaka and Yoriko Kawaguchi). Against the backdrop of numerous scandals of various natures that have seriously undermined the reputation of the Japanese ruling party and the country’s government, Prime Minister Kishida received another blow in connection with plans to hold the Expo-2025 international exhibition next year in Osaka, Japan’s second largest city.

This time the head of government was opposed by Minister of Economic Security Affairs Sanae Takaichi, who late last week expressed the view that preparations for Expo-2025 were inappropriate due to the difficult situation in the country. ‘Expo-2025 should in no way affect the reconstruction of the earthquake-hit Noto district,’ Sanae Takaichi warned, recalling the rising prices of construction materials and labour shortages. However, Cabinet Secretary General Yoshimasa Hayashi said the government sees no connection between reconstruction work in the quake-hit areas and preparations for Expo-2025, which cannot be delayed.

Numerous scandals have directly affected Fumio Kishida’s credibility. A Kyodo poll conducted back in March showed that the level of trust in the Kishida government has dropped to a record low of 20.1 per cent. 64.4 per cent of respondents do not support the cabinet’s activities. The level of approval of the ruling LDP fell to 24%, the lowest level since December 2012. The main reason for the fall in the rating of the government and the LDP was the turmoil in the ruling party. More than 77 per cent of respondents thought that the party functionaries who had disgraced themselves should be severely punished. Although the latest NHK poll showed a slight increase in support for Fumio Kishida to 25 per cent in August, 74 per cent of respondents did not want him to remain in office after the LDP leadership election in September.

‘New Capitalism’

But not only scandals hit Prime Minister Fumio Kishido. One of the main reasons for Kishida’s and the ruling LDP’s falling approval ratings has been economic problems and the rising cost of living. According to Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, wage growth has not kept pace with inflation, forcing households to cut back on spending, including on food, for the seventh month. Upon coming to power in 2021, Kishida inscribed on his political banners his intention to make a U-turn from global capitalism, which leads to widening economic inequality, to a ‘new-formation capitalism.’

In Kishida’s statements in 2021, key to the ‘new capitalism’ was the creation of a ‘virtuous cycle of growth and distribution,’ a broad set of social support measures for all segments of the population.’ At the time, some economists met this idea of Kishida’s with hostility, considering it ‘socialist’. This increased the wariness of the right wing, which favoured ‘abenomics’. So the idea of a ‘new capitalism’ had to be adjusted, and in 2023, two aspects were emphasised. The first is comprehensive labour market reform, where ideally employees are in a constant process of upgrading their qualifications or acquiring additional skills in response to market demands, and companies allocate significant resources to continuously index employee wages.

The second aspect is the creation of dynamic start-ups in promising industries that will revitalise the market, attract investment and contribute to the development of peripheral areas. At the same time, special attention should be paid to stimulating the application of artificial intelligence capabilities, in particular chatbot ChatGPT, in financial, educational, industrial, medical and other spheres. Despite the optimism of the announced strategy, it seems that its practical implementation has encountered a number of problems, the main of which is the sources of funding.

Kishida pulled Japan out of the COVID-19 pandemic with massive stimulus spending. To revive the economy, the government approved a package of measures to revive the economy totalling 17 trillion yen ($113 billion), including a single 40,000 yen ($266.5) per person income and residence tax cut and 70,000 yen subsidies for low-income households. However, 62.5 per cent of respondents disapproved of the campaign, according to the Kyodo poll. 40.4% of respondents explained their decision by saying that the government still plans to raise taxes in the future to cover the doubled defence spending. The income tax cut was generally perceived by the public as a ‘cynical attempt at bribery’ and did not win Kishida’s cabinet any political points.

The economic situation continued to be critical. Japan fell into recession and lost third place to Germany in the ranking of countries with the highest GDP. In the last three months of 2023, Japan’s GDP fell by 0.4 per cent. compared to the same period in 2022.

The cause of economic problems most economists cite the weakness of Japan’s national currency, the yen. Over the past two years, the Japanese yen has fallen in value against the dollar by almost 23%. The main reason for the weakening of the currency was the divergence between the ultra-soft monetary policy of the Bank of Japan and expectations of further tightening of the U.S. Federal Reserve policy in order to stop the growth of inflation, which has reached a maximum for four decades. To get the economy out of the radical monetary stimulus he appointed scholar Kazuo Ueda to head the Bank of Japan.

In July, the Bank of Japan unexpectedly raised interest rates amid rising inflation, contributing to stock market volatility and a sharp rise in the yen. In early August, Japan’s Nikkei 225 index fell 5.8 per cent. This was the index’s strongest one-day decline since March 2020, when stocks fell due to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Japan’s other index, the TOPIX, fell more than 6 per cent. Analysts attributed the decline to a key rate hike by the Bank of Japan, a dump in semiconductor maker stocks and the release of data showing a slowdown in the U.S. economy.

Despite the fact that Kishida’s ‘new capitalism’ did not bring the expected results in a strategic sense, certain tactical successes still took place. During his rule, wage growth has reached levels not seen in decades, but skyrocketing prices in the country continue to restrain consumer spending. In addition, in the eyes of the public, the prime minister’s own actions were constantly perceived as ‘reacting to the situation’ and did not appear to follow a clear policy course. In addition, the sharp fluctuations in the stock market and the yen have negatively affected his image as a cautious economic manager, preventing him from fully shedding his unpopularity label.

Security policy

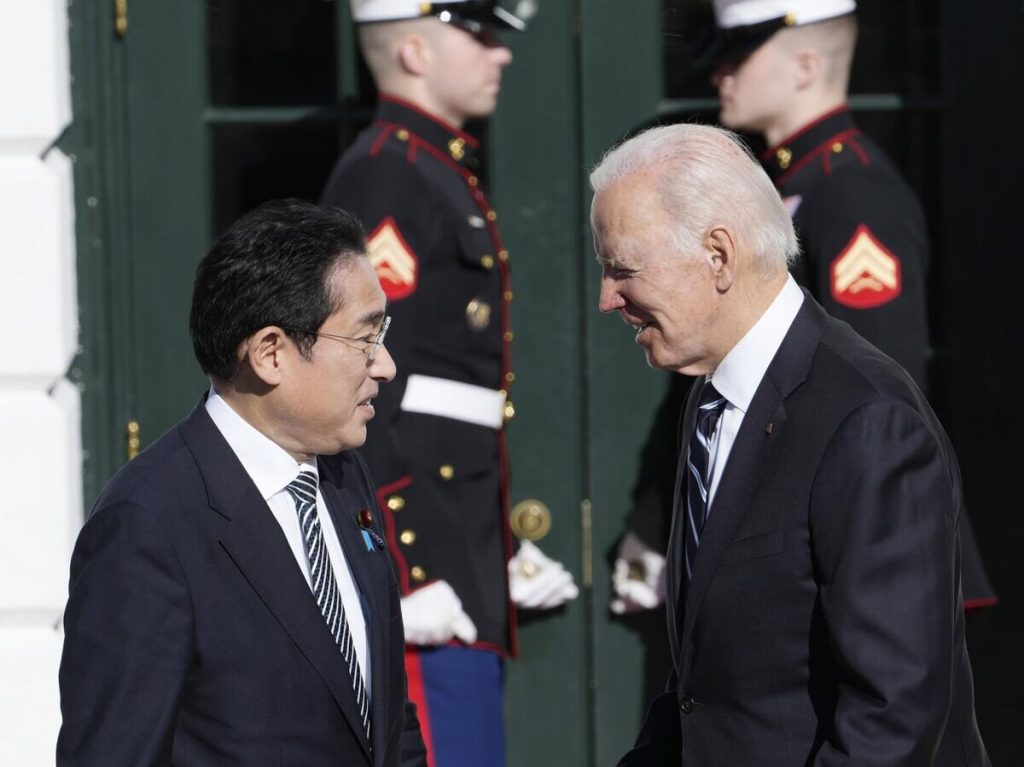

Kishida’s position looked most advantageous in foreign policy and defence matters. Japan’s main foreign policy partner was and remains the United States. This is evidenced by the fact that one of the first to express his gratitude to him, after Kishida’s statement not to run for LDP leader, was US Ambassador and his main admirer Emmanuel Rahm. He hailed the ‘new era of relations’ over the past three years. And noted that Kishida and President Biden had laid a solid foundation for the alliance to continue. Biden himself also praised Kishida, saying in a statement that his leadership has been historic.

During Fumio Kishida’s state visit to the US, Tokyo and Washington signed about 70 defence cooperation agreements. ‘This is the most significant renewal of our alliance since its inception,’ White House chief Joe Biden told reporters after two hours of talks with Prime Minister Kishida. In particular, the two sides agreed that the U.S. military will establish a joint command structure with its Japanese counterparts to ensure ‘seamless and effective’ teamwork, especially in crisis situations, which Tokyo and Washington have long understood by default to mean, most notably, a possible Chinese invasion of Taiwan. In addition, the two allies decided to develop a joint air and missile defence network in the region together with Australia, as well as to hold trilateral military exercises together with the British armed forces.

A kind of ‘cherry on the cake’ for Tokyo was the US decision to allow two Japanese astronauts to participate in the American lunar exploration programme Artemis, and in the foreseeable future to allow one of them to become the first non-American to land on the Moon. In April this year, he became only the second Japanese prime minister to address a joint session of the US Congress – before him, only Shinzo Abe did so in 2015.

In addition, the US, UK and Australia have attempted to bring Japan into the AUKUS alliance. However, Japan has so far refrained from this proposal. In addition, Japan has been actively engaged in building up its defence capabilities, motivated by the growing threats from China, DPRK and Russia. One of the most important milestones on this path was the creation last summer of a trilateral alliance with another American ally in Asia, South Korea. Kishida has significantly improved relations with Seoul by establishing contacts with South Korean President Yun Seok-yeol.

In July of this year, just in time for the NATO anniversary summit, the Japanese government published the Defence White Paper, an annual report on the threats facing the country and ways to counter them. Presenting it, Japanese Defence Minister Minoru Kihara noted that the existing order is seriously challenged. And according to the White Paper, this challenge for Japan is posed by a trio of neighbours: China, Russia and North Korea. The authors of the White Paper pointed to the possibility of a ‘serious situation’ in East Asia, similar to what happened in Ukraine. China’s aggressive behaviour is to blame, in particular its series of military exercises off Taiwan, which ‘demonstrate part of Beijing’s invasion strategy’. Japan is also concerned about the closer ties between Beijing and Moscow, which are reflected in the increasing frequency of joint military manoeuvres between the two countries around Japan and their coordinated actions at sea and in the air, ‘with warships entering Japanese waters and bombers flying along the Japanese archipelago’.

Russian-Japanese relations have not been the easiest during Fumio Kishida’s nearly three years in office either. After the beginning of Russia’s large-scale aggression against Ukraine, Japan, unlike a number of other Asian countries that tried to distance themselves from these events as much as possible, was at the forefront of anti-Russian actions. Tokyo not only supported sanctions against Moscow, but also began to persuade other countries in the region to take a tough anti-Russian stance. In mid-June this year, Tokyo even more specifically pledged its support as part of a 10-year, $4.5 billion security agreement signed by Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on the sidelines of the G7. From Tokyo’s perspective, the war in Ukraine has called into question Asia’s security architecture. As a result, not only Japan but also countries such as South Korea, Taiwan and the Philippines are strengthening their alliances with each other and with the US. And in return for its commitment to Europe, Tokyo now wants the support of the free world in the event of a Chinese attack on democratic Taiwan.

Another country that has traditionally been a source of concern for Japan is North Korea, which as recently as 2017 threatened to ‘drown four small islands in the Japanese archipelago in the sea with Juchei nuclear bombs’. The DPRK’s military buildup over the past year ‘has been marked by enhanced nuclear and missile capabilities, including diversification of missile platforms and improved intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance’ and now ‘North Korea’s military activities pose an even more serious and immediate threat to Japan’s security than ever before.’ And then there is the predictable concern about deepening military ties between Pyongyang and Moscow.

Back in 2022, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida pledged to raise defence spending to 2% of national GDP by 2027 with a five-year plan worth ¥43.5 trillion ($273 billion). However, according to the current document, 42% of that amount has already been used. Most of the money has gone to building new warships equipped with the Aegis system, reinforcing facilities and bases, and strengthening ‘counterattack capabilities’ with improved missiles (both domestic and US Tomahawk). This year, Japan’s defence ministry is requesting a record budget of more than 8 trillion yen ($54 billion) for fiscal year 2025 (beginning next April). Such a request would exceed the record 7.9 trillion yen initial budget for fiscal 2024, which runs through next March. The expected request would include spending to purchase attack drones to protect the security of the southwestern Nansei island chain, which is strategically important because it is close to Taiwan.

Regarding the sources of funding for the increased defence spending, Kishida showed willingness to partially cover it through tax increases, noting that ‘the responsibility for this lies with us who are alive today’. The Japanese government intends to raise tobacco tax, corporate tax and disaster recovery tax. Incidentally, there is a desperate debate within Japanese politics, including within the ranks of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party of Japan, on how to finance defence spending. Some members of the LDP are in favour of covering, at least partially, the costs by issuing special government bonds. However, Prime Minister Kishida would like to avoid issuing new bonds, as this would increase the country’s public debt (analysts estimate that by the end of the current fiscal year, public debt will exceed 1 quadrillion yen, or 262.5 per cent of GDP, the highest among the G-7 countries ). Therefore, other factions are in favour of imposing additional defence taxes in the country. However, such steps are now unpopular in the country: a poll conducted last year showed that 53.6% of the Japanese population opposes the introduction of a new defence tax, while 39% support the government’s move.

Legacy and heirs

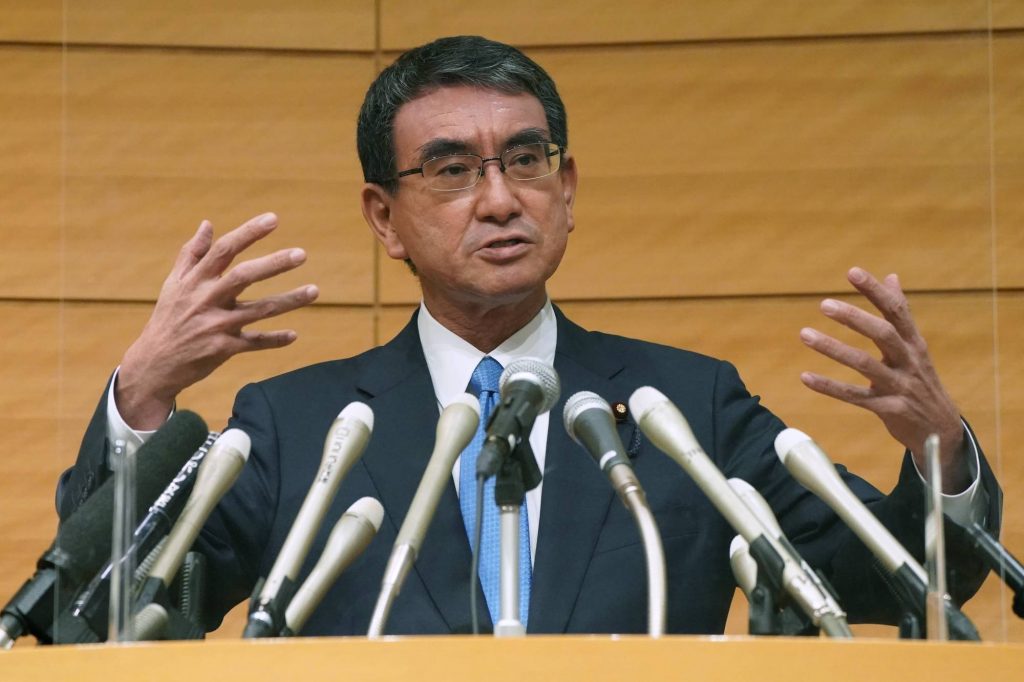

Fumio Kishida took over the leadership of the Liberal Democratic Party in September 2021 largely due to the strong support of party heavyweights, who in Japanese political life have always been more important than the sympathies of ordinary Japanese voters. Otherwise, he would not have been able to beat his main rival – former Foreign Minister and Defence Minister Taro Kono, who is much more popular among ordinary party members and Japanese voters, but is considered by the party top brass to be too unpredictable and insufficiently conservative.

According to some reports, notably by Kyodo news agency, the party’s political heavyweights are not so favourable to Kishida this time around. Although in June, despite his falling rating, Kishida cheerfully declared that he was ready to compete for the post of party leader. Speaking in the Japanese parliament, he unexpectedly proposed new policy measures clearly aimed at winning the party leadership: as a response to rising consumer prices, he proposed to return benefits for paying electricity and gas bills, as well as lump-sum payments to pensioners and some other categories of citizens.

If all this was undertaken with the aim of his re-election as party leader, it becomes necessary to explain what has happened recently, breaking the all-out will to be re-elected. At a press conference on 14 August, he evaded a direct answer to the question of when he made his decision, limiting himself to explaining that he made the decision because leaving was necessary to restore confidence in the Liberal Democratic Party by showing his strength of will as a politician. However, as Japanese political analysts point out, Kishida’s decision could have been influenced by the refusal to support him by party vice president Taro Aso, head of one of the influential factions within the party. As the incumbent prime minister, he cannot run unless he is guaranteed victory and he needed Aso’s support as well. It is considered unseemly for a sitting LDP chief to run for office and be defeated. So without sufficient support, it was preferable for him to drop out and try to maintain his influence in another capacity in the future.

Fumio Kishida, like US President Joe Biden, was therefore forced to come to terms with the harsh reality. However, unlike the US President’s quick endorsement of Kamala Harris, there is no clear successor in Japan. True to his immediate statement of refusal to run for party leader, he urged his cabinet ministers mulling their nomination to not hesitate to stand for election, an unprecedented move for a sitting prime minister. Ministers should ‘participate in the debate openly, without hesitation, to the extent that it does not interfere with the performance of duties,’ he said.

Now the country is facing the most interesting leadership vote since the late Shinzo Abe shocked everyone with his comeback 12 years ago while the LDP was still in opposition. Abe faced little real competition during his years in power, and in 2020, after he resigned for health reasons, the party quickly rallied around his right-hand man, Yoshihide Suga. The following year, when Suga relinquished power, Kishida became the logical choice.

Today, most analysts believe that predictions about who will win the party elections are meaningless. Among the most frequently mentioned contenders are former Defence Ministry chief Shigeru Ishiba and Taro Kono, the current head of the digital technology ministry.

Ishiba, 67, regularly tops the list of politicians voters would like to see as the next prime minister. His record includes serving as party secretary-general from 2012-2014 and the fact that he has already run for LDP chief four times. He will have little trouble gaining the support of the 20 lawmakers needed for candidates to enter the race, which will be decided among the party’s 1.1 million members.

Taro Kono is also popular with the electorate. He lost to Kishida in the last party leadership election due to a lack of support from his parliamentary colleagues. However, the fact that he is seen as an outsider may play to his advantage. Kono has extensive experience in the Cabinet, having served as foreign minister and defence minister. Current Foreign Minister Yoko Kamikawa is also among the contenders. The 71-year-old Harvard graduate, if selected, could become the first female prime minister.

Another possible contender is Toshimitsu Motegi, 68, the current LDP secretary general, who was foreign minister from 2019-2021. He is considered a political heavyweight. He is also a Harvard graduate. Some Japanese analysts believe that Motegi could develop a good personal relationship with Donald Trump if he wins, if he in turn wins the presidential election in November.

Shinjiro Koizumi may well decide that his hour has come. The son of former Prime Minister Junichiro has attracted attention for surfing off the coast of Fokushima in an attempt to calm the public following the release of sewage from a destroyed nuclear power plant nearby. A 43-year-old former environment minister and renewable energy advocate, he has criticised government support for coal-fired generation. He was the first sitting cabinet minister to take parental leave. He is also remembered for saying at a press conference in 2019 that he wanted to make the fight against climate change ‘sexy’, a remark that many in Japan took as a gaffe.

Of all the possible candidates so far, only Economic Security Minister Sanae Takaichi, 63, has unequivocally declared her prime ministerial ambitions. She has held her post since 2022, entered politics in 1993 after being elected to the House of Representatives, and has held a number of ministerial posts in the Abe government. She has already run for the LDP chairmanship – in 2021, Takaichi competed against Kishida, but was eliminated in the second round. Japanese media describe her as a politician ‘with the stance of a staunch conservative’. He is a favourite of the party’s ‘right wing’. But the choice of Takaichi, a frequent visitor to the Yasukuni Shrine, considered a symbol of Japan’s past militarism, could jeopardise the recent rapprochement with South Korea and further worsen relations with China.

With just over a month to go until the election, it is possible that rather than trash the party will unite around a core candidate, one who is young and least associated with the activities of the ‘old party guard.’ For him, the main priority will be to restore confidence in the party before the next parliamentary elections, which will not take place before October next year. Kishida’s successor will also have to pay the greatest attention to the domestic political situation. Kishida’s ‘New Capitalism’ economic course has failed, spooking the markets and earning him the derisive (and undeserved) nickname ‘The Four-Eyed Tax Speculator.’ So the successor will need to emphasise the domestic economy, but naturally he cannot ignore the rising tensions with Taiwan and North Korea, as well as Trump’s possible return to the US presidency.

According to many observers, despite the scandals and economic problems, there is no alternative to the Liberal Democrats in the current political situation. The opposition in the country is fragmented and there is no talk of it coming to power in the foreseeable future.