For 25 years, the real power in Venezuela has been in the hands of the “Chavistas” – the political force to which Hugo Chavez gave life. It is very symbolic that on his birthday, 28 July, Venezuela held presidential elections. It is worth noting that these elections, originally planned for 2025, were the result of a compromise between Venezuelan President Nicols Maduro and the United States.

Following the negotiations between the government and the opposition, which took place in Barbados in October 2023 under the patronage of Washington, it was agreed that the presidential elections will be held in 2024, not 2025. The government also guaranteed that the elections would be free and fair, international observers would be allowed to attend, and opposition candidates would be allowed to appeal court rulings barring them from the electoral process. The deal also paved the way for the easing of a series of US restrictions on Venezuela’s oil and gas sector, which has reportedly lost more than $232bn from US sanctions since 2019.

In this piece Ascolta analyses the socio-political situation in Venezuela, as well as the prospects for further escalation of the internal political situation amid the turmoil caused by the presidential elections in the country. The piece also explores possible prospects for the state’s foreign policy, as well as the risks and threats facing the whole of Latin America.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

After reaching such agreements both in the ranks of the Venezuelan opposition and in the United States, not everyone was not happy about Washington’s steps towards the official Caracas, fearing that the easing of sanctions will increase the authority of President Maduro before the elections in 2024. Formally, Maduro has fulfilled the agreements with Washington. Another thing is that the result was not in favour of the opposition.

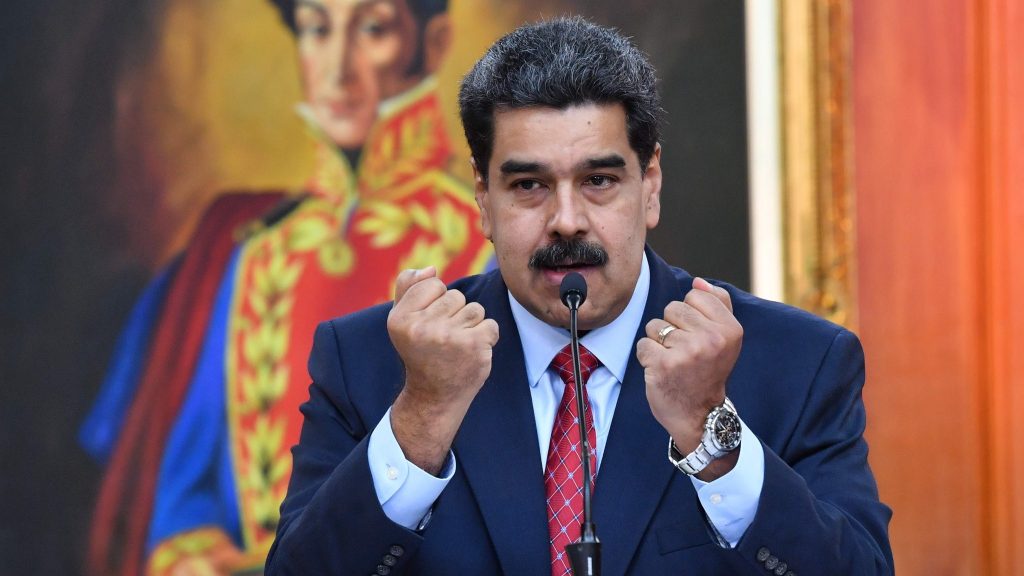

The announced election results, according to which Nicolas Maduro was re-elected for a third term with 51 per cent of voters’ support and his opponent, former diplomat Edmundo Gonzalez, got 44.2 per cent of the votes, sparked protests from the opposition, which claims to have evidence of electoral fraud and the “undeniable victory” of its candidate, Edmundo Gonzalez. It claims it was the opposition candidate who won 70 per cent of the vote.

Opposition representatives said that their observers were given access to less than a third of the ballots. It should be noted that voting in Venezuela is electronic: voters press a button for any of their preferred candidates on the voting machine and the results are instantly sent to the headquarters of the National Electoral Council. The machines also print out paper ballots, which by law all observers have access to count. But, allegedly, in most cases, opposition members were simply kicked out of polling stations without being allowed to participate in the counting process.

After the announcement of the election results, riots broke out in the country, accompanied by the demolition of monuments to Hugo Chavez, the burning of portraits of the official winner of the election and clashes with the police. As many observers note, the political crisis in Venezuela is unlikely to end quickly, and domestic and international pressure on the country’s authorities will only grow. Let’s try to understand the causes and consequences of what is happening in Venezuela.

Chavez’s heir

Nicolas Maduro, 61, who was once a bus driver and had no higher education, but reached the post of vice-president under the popular Hugo Chavez, became head of state in April 2013 – in fact, by the will of his predecessor. But even with the patronage of Mr Chavez, who before his death from cancer bequeathed Venezuelans to bet on Nicolas Maduro, he beat his then rival Henrique Capriles by just 1.5 per cent of the vote.

Opposition members of parliament labelled the winner illegitimate and ignored his inauguration. This created tensions in Venezuelan society that persist to this day.

The legacy of Hugo Chavez, which Maluro inherited, came with a host of problems that have only worsened under the new president. Venezuela’s public debt by the time Maduro took office was about 70 per cent of GDP, with a budget deficit of 13 per cent. Simply put, the country was living in debt and was saved only by high oil prices.

It should be understood that the governments of both Chavez and Maduro, “leftist” in their political orientation, paid a lot of attention to social problems. High oil prices allowed the governments to invest a lot of money in “social welfare”, thus creating a social base of “Chavista” supporters. However, the fall in oil prices led to the end of the “social paradise” and the government was forced to look for other tools to replenish the budget. Thus, under the slogan of fighting corruption, having decided that the reason for exorbitant prices for the population was the greed of businessmen who charged hundreds of per cent on purchase prices, it initiated a series of arrests of owners of household goods shops and nationalised the Daka retail chain. However, confiscating goods and selling them at a reduced price did not help tackle shortages and inflation, which stood at 56 per cent in the first year of Maduro’s presidency.

The situation did not improve in 2015. The global drop in oil prices and the global economic crisis led to a new round of price increases in consumer goods. Inflation in the country was already 181%. And the national currency, the bolivar, even had to be devalued by 37% in 2016. Hyperinflation and total shortage of essential goods provoked a large-scale humanitarian crisis in the country. People complained about the lack of food, exorbitant prices rising day by day and the collapse of the medical system. Between 2016 and the first half of 2018, between 1.6 million and 4 million people (3.5-10 per cent of the population) left the country, according to various estimates, of whom 90 per cent arrived in various South American countries. After this wave, migration slowed down but continues to this day. In total, more than 7.3 million people emigrated from Venezuela between 2014 and 2023.

In December 2015, the Venezuelan opposition gained a majority in parliament and began to promote the idea of a referendum on President Maduro’s resignation. And this against the backdrop of the intensification of all the previous problems, to which was added a severe energy crisis. Since March 2017, a new phase of dual power began. The Supreme Court announced that it was stripping the deputies of the National Assembly of their immunity and taking over the functions of parliament. The MPs, of course, were not satisfied with this arrangement. They set up a special commission to replace the judges of the Supreme Court. And once again, the country was in turmoil, which was not without casualties. By May, Maduro came up with a scheme to strengthen his power, while trying to calm the public: he initiated the creation of the Constitutional Assembly, the purpose of which was to prepare a new basic law of the country. According to the authorities’ plan, the elections to the assembly were supposed to reconcile the conflicting parties, but the result was the opposite. The opposition ignored the vote and most Latin American countries refused to recognise the results. President Maduro was not embarrassed by this: very soon the Assembly gave itself the powers of parliament, including the adoption of laws.

On 20 May 2018, Nicolás Maduro was safely re-elected with 67.84% of the vote. This time, the united opposition, represented by the Round Table of Democratic Unity (MUD) coalition, deemed their participation in the election pointless, calling for a boycott of all their supporters. “We have not chosen a presidential candidate as many are in detention, under house arrest or have been forced to flee abroad. The election is a farce, a simulacrum that will result in Nicolas Maduro declaring himself president,” Juan Guaido, then head of the MUD faction in the opposition-controlled parliament, declared unequivocally on the eve of polling day. He predicted that after the election, “Venezuela will have a very difficult period.” “The authorities will plunder the people even more. And this will be accompanied by the non-recognition of Nicolas Maduro and the so-called Constitutional Assembly by most of the democratic world.” Western countries did not recognise Maduro’s victory. The day after the election, then US President Donald Trump signed an executive order that banned Americans from any transactions with Venezuelan government debt.

In January 2019, Mr Guaidó, as speaker of parliament, went wah-wah, declaring himself acting president. He justified his actions by the article of the Constitution, according to which, in case the president is unable to fulfil his duties (for health reasons or in case of recognition of incapacity by members of parliament), power is transferred to the head of the National Assembly. The powers of the politician were immediately recognised by US President Donald Trump, followed by a total of more than 50 states.

At the same time, Washington imposed sanctions that implied, among other things, a complete halt to oil supplies to the US. This was a serious blow to a key industry for Caracas, especially given that Washington threatened secondary sanctions to all those countries and companies that would not refuse further co-operation with Caracas in this area. Meanwhile, Russia, China, Cuba, Mexico, Iran, South Africa and a number of other countries continued to recognise Nicolas Maduro as head of state and to criticise the US with varying degrees of severity for its policy in Venezuela.

Meanwhile, the recognised opposition wasted no time. An interim government was established and embassies were quickly opened in countries that recognised Mr Guaido’s leadership. Diplomats of the new Venezuela were also accredited to international organisations. One of their key tasks was to obtain the right to dispose of the blocked assets of the Bolivarian government. The progress towards the goal was variable. But what was definitely not achieved was a change in the situation in Venezuela itself: Nicolás Maduro has not only not lost power, but has gradually consolidated it. In December 2022, the “Juan Guaido for President” project was closed: the parliament (the one still controlled by the opposition) voted to dissolve the interim government. On 5 January 2023, the Venezuelan embassy in the US, controlled by Guaidó’s supporters, ceased operations.

Maduro’s stronghold

Why did Nicolas Maduro manage to endure and strengthen his position for so long? By the way, these reasons will give a key to understanding the current situation in Venezuela.

The stability of the Maduro regime is influenced by a number of factors. Firstly, the legacy of Hugo Chavez, who 11 years after his death is much more popular in the country than the current president. Nicolás Maduro himself recalls his mentor in almost every speech he makes. “I am not Chavez, if you judge strictly on intelligence, charisma, historical power… I am Chavez’s son, that’s how I feel. And I never thought that he would entrust me with such a responsibility,” he said, in particular. And even in his victory speech in 2013, as soon as he got up on stage, he said: “Mission accomplished, Commander Chavez! You left behind a son, and your son is now the president of Venezuela”.

Secondly, support for the poor. Despite the fall in oil prices, Nicolas Maduro has tried to preserve as much as possible the social course of his predecessor, aimed at supporting the poorest segments of the population. Third, support for the military. For all authoritarian regimes, support for the military is a key factor of stability. Venezuela is no exception. Law enforcers: police officers and officers of special services remain loyal to the Chavistas.

The unconditional support of the latter was seen during the coup attempt in 2017. Then former police officer Oscar Perez hijacked a helicopter, fired on and threw grenades at the Supreme Court building. In a video that went viral on the internet, he called for an uprising against “the impunity of the current government, against tyranny”. But the law enforcers did not heed the call. The loyalty of the security forces is clearly demonstrated by the mass protests that have repeatedly engulfed Caracas and many other cities in the country during the ten years of Nicolas Maduro’s rule. In total, at least 276 people have died in them and more than 18,000 have been injured.

Another factor in cementing the Maduro regime is mass emigration. The Venezuelan authorities immediately realised that it was pointless and dangerous to keep all dissenters inside the country, thus increasing the pressure level in the cauldron. As we have already noted, more than 7.2 million Venezuelans have left the country in a decade, according to the UN. And this is the largest migration crisis in South American history. All those who left are Venezuelans who are sceptical of the government. But the Chavistas stayed – and helped strengthen the regime.

The arch-important condition for “unsinkability” is tight control of elections. The opposition recognises that Chavism is popular among certain sections of society. But at the same time it claims that none of the recent elections is without fraud. There were talks about this as far back as 2013 (when, as we recall, Henrique Capriles lost to Nicolás Maduro by 1.49 per cent). Mr Capriles’ team recorded more than 3,500 violations and demanded a recount of all 100% of ballots. The demand was not fulfilled, and mass protests began in the country. But they had no effect on the decision of the National Electoral Council (CNE) of Venezuela.

After that, the algorithm was repeated many times: elections – non-recognition of the results by the opposition and its associates abroad because of “numerous violations” – no positive reaction from the authorities. The opposition’s claims were never limited to what happened on election day. It was always about the inadmission of candidates to the election races for various reasons, about unequal conditions during the campaigns, and about bribery of voters (for example, with the help of food packages).

It must be said that the opposition itself has had a hand in the survival of the Maduro regime. Its mistakes and not always effective actions only strengthened the regime. In 2019, Juan Guaido received unprecedented support from the international community, his associates disposed of Venezuelan diplomatic property in the United States and money from the Central Bank of Venezuela – but they have not developed a clear plan on how to get their hands on real power. Before that, back in 2015, the opponents of the authorities overestimated their strength after their triumph in the parliamentary elections: they then took control of the country’s main legislative body, but failed to reach out to the other half of their fellow citizens. The Venezuelan opposition clearly lacked unity. About this, by the way, in one of the interviews Juan Gaido.

There are several explanations for this. And first of all, the fact that as soon as one of the opposition leaders in Venezuela starts to gain popularity and becomes really potentially dangerous for the regime, Maduro starts to put pressure on him. Some kind of criminal prosecution is organised, or the person simply disappears for a while. In general, something is invented and done to get rid of a competitor. What is happening to oppositionists in this country, among other reasons and squabbles that prevent them from being in solidarity, is a tragicomedy that has to do with the way politics is organised and works in Venezuela.

Despite all previous failures, the Chavistas’ opponents were determined to defeat Maduro in the 2024 presidential election and to present a united front to do so.

The Iron Lady of the Venezuelan opposition

For the 2024 presidential election, the Venezuelan opposition was preparing very seriously. In July last year, Maduro’s opponents held a debate, as they say, in the best traditions of American election campaigns, and in August, the participants of the future opposition primaries in writing recorded that they would support the winner of the presidential election in 2024.

The primaries were held on 22 October 2023. Initially it was planned that 13 candidates would take part in them. Among the famous names was Henrique Capriles, who lost 1.5 per cent to Maduro in the 2013 elections. But in the end, three candidates one after another abandoned their ambitions in favour of one person – 55-year-old Maria Corina Machado, who was considered the favourite from the start. 92.35% of the votes in favour of Maria Corina Machado – this was the final result of the Venezuelan opposition primaries.

Machado has become a living symbol of Venezuelan discontent with the regime, completely eclipsing all her predecessors and other leaders of the anti-socialist camp – from the failed “alternative president” Juan Guaido, who last year ignominiously fled to the U.S., to passionaries of the old days like Leopoldo Lopez or Enrique Capriles (the former, after a prison term and torture, also emigrated to Spain, and the latter still remains in Caracas). Her associates and supporters have long called this lady “Venezuela’s Margaret Thatcher” and “our Iron Lady” – and she herself explicitly says that it is Thatcher who she considers her idol.

Maria Corina Machado was not initially at the forefront of the opposition, but she has been known in the country for a long time. Back in 1992, she founded the Athena Foundation, which collected donations for poor Venezuelan children. In 2005, she represented Venezuelan civil society at a meeting with U.S. President George W. Bush Junior, for which she was immediately labelled a “CIA puppet” in her home country. In 2011, she became a member of parliament, and in November 2012, Maria Corina Machado founded the opposition liberal movement Vente Venezuela (Come on, Venezuela), from which she is still running.

In March 2014, the fate of the oppositionist made a sharp turn. She spoke at a meeting of the Organisation of American States with a report on the situation in Venezuela, and did so as a “representative of Panama”. The Chavistas immediately accused Mrs Machado of betraying her homeland. As a result, she was stripped of her mandate as a member of the National Assembly. This was followed by a new trial, this time linked to the large-scale protests provoked by the detention of one of the opposition leaders, Leopoldo Lopez. In 2014, Mrs Machado was formally charged with public calls for mass riots and then with involvement in a plan to assassinate Nicolas Maduro. As part of the investigation into the second case, she was banned from leaving the country.

In 2015, the oppositionist was banned from holding public office for 12 months after being accused of providing incomplete information about her income in her declaration. This thwarted her plans to run in parliamentary elections that year. But, as it later became clear, Maria Corina Machado’s political ambitions were not affected by the ban.

Maria Corina Machado did not overcome the barrier of primaries at the first attempt. Thus, she tried to take part in the 2012 elections, but then gained only 3 per cent in the opposition race. And the first place went to Henrique Capriles, who then lost to Hugo Chavez with less than 1% of the votes. In those years, Ms Machado was largely a marginal figure, scaring off a large part of the electorate with her radicalism.

Machado does represent the most radical wing of Maduro’s opponents. They believe negotiations with the regime are pointless and that the only way to destroy it is through civil disobedience. The oppositionist is often labelled as far-right. Her ideals are free market, non-interference of the state and “society without crutches”, i.e. excessive state care for the poor. Machado, however, shrugs off any labelling, saying there is no left or right in the modern world. “Ideologically, I am a liberal. I believe in democracy, the rule of law, private property and the market,” the politician said in an interview.

Machado is sure that her victory will turn the situation not only in Venezuela – it will be “the final blow to leftist regimes, as in Nicaragua and Cuba.” Naturally, relations with Russia will also change dramatically. After the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russian troops, Maria Corina Machado said, “The regime’s representatives say that Venezuela is with Putin. This is a lie. We Venezuelans are with the citizens of Ukraine.”

She also spoke about the importance of fighting “organised crime, drug trafficking, international terrorism, guerrilla actions, with Cuba, Iran, China and Russia”. And speaking at a conference with the title “America’s Countries and Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” the politician listed what she strongly disagrees with: “Russia controls Venezuela’s oil” and “most of the finances” of the country, as well as having “enormous influence over the armed forces.” Venezuela, she said, has become “a platform for the spread of Russian influence in Latin America.” After the elections, the oppositionist claims, all of this will be over.

However, Machado was not allowed to participate in the presidential elections. Just days after the opposition primaries were held, Venezuela’s Supreme Court declared them illegal, and in late January this year confirmed a 15-year ban on Ms Machado and two other opposition figures “for participating in a corruption scheme organised by Juan Guaido”. In response, the US renewed sanctions against Venezuela from April 2024.

The oppositionist herself has long maintained her bid to run for office, but has also not explained her strategy for overcoming the injunction. Pressure was therefore mounting in the opposition camp for Mrs Machado to identify a replacement. In the end, she found a man among her friends who has run as a presidential candidate virtually in her name and who represents her programme and her fight against Maduro and “Bolivarian socialism”. His name is Edmundo González Urrutia. He is already an elderly former diplomat (he is 74 years old), according to his entourage – fundamentally always polite and quiet, very well educated intellectual with a soft voice, fond of birds and raising grandchildren.

The new candidate built his career in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He worked in El Salvador and Belgium, and in 1978 he became first secretary to the Ambassador of the Bolivarian Republic to the United States. In addition, from 1991 to 1993, Gonzalez was Venezuela’s ambassador to Algeria, after which he headed the main department of international policy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and in 1999 arrived in Argentina, where he became ambassador. In this position, he promoted the republic’s accession to Mercosur, the common market of South American countries. Despite González’s efforts, Venezuela’s membership in the organisation was suspended in 2017.

Together with Maria Corina Machado, they made quite a powerful pair. All Venezuelans unhappy with the regime understand that by voting for González, they will in effect be giving votes to Machado and her programme. In the last election week, the duo held very successful rallies in several provincial capitals, attended by tens of thousands of people. In her speeches, Maria Corina Machalo promised, if her friend and representative Edmundo González Urrutia wins the election, to rebuild the economy, end repression, strip the intelligence services of their omnipotence and permissiveness, and restore dignity to Venezuelans, many of whom have seen meat or writing paper and toilet paper only a few times in their lives – or not at all. “I will forever bury such ‘socialism’ and build a state where criminals and corrupt officials in uniform will be in prison,” Machado declared.

The result at any cost

There was no special intrigue as to whether Nicolas Maduro, who has been in power in Venezuela since 2013, intends to “extend” for another term. It was obvious to both the local population and the international community that Mr Maduro would not want to limit himself to two presidential terms and would run for a third consecutive six-year term in 2024. It is true that initially Mr Maduro was vague about his participation in the elections. However, in March 2024, the story was finally put to rest. The congress of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela officially nominated Maduro as a presidential candidate. “There is only one outcome – the victory of the people on 28 July,” the newly minted candidate himself solemnly promised, addressing his supporters at a rally in Caracas on Saturday, “They couldn’t stop us and they won’t be able to. President Maduro did not specify who they were, but it is clear that he meant primarily opposition forces. Maduro outlined his electoral strategy by declaring that he intended to win “not by sleight of hand, but by carnage,” and a few days before the vote he warned that in case of his defeat the country would face a “bloodbath”.

Despite the opposition’s claims that Maduro will 100% falsify the elections, many experts agreed that he will first try to bet on victory, so to speak, on “legal grounds”, though using technologies related to administrative resources. Purely technologically, he had to solve one main task – to mobilise his supporters as much as possible and bring them to the polling stations. It is no secret that many Chavistas were disappointed with Maduro. And there were objective reasons for this.

These included electoral fatigue from eleven years of Maduro’s rule, and the deterioration of the socio-economic situation, accompanied by falling GDP, hyperinflation, hunger and flight from the country. As local experts have pointed out, half of the roughly five million votes Maduro probably needs to win are votes from people who may simply stay home because they are not excited about voting for him. To meet this challenge, he has gone off the beaten track by exploiting the image of the enemy. During the current election campaign, Maduro, as usual, has been lashing out at his opponents, labelling them as “fascists manipulated by the enemies of the homeland and world imperialism led by the United States”, who, he says, “dream of seizing Venezuela’s natural wealth”, especially oil and mining, and “imposing Western values on Venezuelans that are alien to them”.

The second challenge Maduro faced was to reduce opposition voter turnout. The authorities, for example, deliberately created confusion on the eve of polling day by renaming some 6,000 schools that normally serve as polling stations and whose addresses locals, many of them illiterate, have long known by heart. Another trick designed to reduce turnout was the insurmountable bureaucratic procedures many overseas voters faced in trying to register. Only about 69,000 Venezuelans successfully did so out of millions of eligible overseas voters. П

he election campaign in Venezuela has been accompanied by a series of arrests. In March, Venezuelan authorities detained members of Machado’s team, accusing them of plotting against the government. A few days before candidate registration was finalised, the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service arrested Machado’s closest associates Henry Alviares and Dianora Hernandez. Then Vente Venezuela regional coordinator Emil Brandt Ulloa was detained and allegedly confessed. to the intention to “attack the barracks, raise the streets and drown the country in blood.” During the same period, Maduro claimed that an assassination attempt was being prepared against him, and those detained in this connection seemed to have already admitted to belonging to Machado’s Vente Venezuela movement.

The opposition was really concerned that the Maduro-controlled Supreme Court could at the last moment withdraw the candidacy of Edmundo Gonzalez, or even refuse to hold the election at all, provoking a national security crisis with Guyana over a territorial dispute over the rich oil region of Essequibo. Recall that Venezuela held a referendum in December 2023 to annex Essequibo. The dispute over this territory with neighbouring Guyana has been going on for 200 years. At the end of the plebiscite, more than 95% of Venezuelans were in favour of the oil-rich region becoming part of the Bolivarian Republic. Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro then declared Guyana-Essekibo the country’s 24th state.

The opposition’s concerns proved unfounded. The elections were held at exactly the scheduled time, and voting will also be organised in the disputed Essequibo territory, according to the authorities. As for Edmundo González Urrutia, he was allowed to participate in the elections, as were nine other candidates, including Maduro himself, who were intended to show the alternativeness of the electoral process. Another opposition candidate, Manuel Rosales, of the opposition New Era (UNT), part of the Democratic Unitarian Platform (PUD), also made the list of candidates. The 71-year-old is the governor of the state of Sulia.

In the 2006 elections, he won 36% against Chávez’s 63%. In 2008 he was forced to leave Venezuela because of the legal proceedings against him – the authorities accused him of conspiracy. Rosales sought political asylum in Peru and returned to Venezuela only in 2015, two years after the death of Hugo Chavez. The charges against him were dropped and he won the election for governor of Sulia in 2021. Rosales is considered acceptable to the authorities as a candidate because he does not have the same support among the population as Machado.

A number of other very colourful characters can be identified. For example, Javier Bertucci. He is a 54-year-old Venezuelan businessman and evangelical pastor, candidate of the Hope for Change party. He was implicated in the Panama Papers leak scandal and in 2010 was charged with aggravated smuggling and conspiracy. He was arrested while trying to move a 5,000-tonne tanker from Venezuela to the Dominican Republic. It was believed to be carrying diesel fuel disguised as paint thinner. The court eventually ordered him to be placed under house arrest. Or Claudio Firmin, a professional “candidate” for president. The 74-year-old politician is running in the presidential race for the Solutions for Venezuela party. In the 1980s he served as deputy youth minister and in the 1990s he was mayor of Caracas’ Libertador municipality. This is not the first time Fermín is vying for the post of head of state. His first attempt was in 1993, at which time he came second with 24 per cent. Another attempt was in 1998, but then the politician withdrew his candidacy, and in 2000 he got less than 3%.

Sociological polls on the eve of the elections said that the main struggle would be between Maduro and Gonzalez. And many of them were clearly at odds with each other, often based on proximity to the government or the opposition. Most polls favoured the opposition candidate to win. According to ORC Consultores, Gonzalez was predicted to win 59.6 per cent of the vote to Maduro’s 12 per cent, and Poder y Estrategia 62 per cent to 28 per cent. The only sociological company that gave Maduro’s victory to Hinterlaces has periodically published data in favour of the government before. According to its data, 55.4 per cent of voters supported the incumbent, while Gonzalez-21.1 per cent. Support for the other eight candidates ranged from less than 1 per cent to 4.5 per cent.

Post-election war

The results of the first exit polls showed the opposition candidate González winning. However, just hours after the polls closed, Elvis Amoroso, head of the National Electoral Council (CNE), announced Maduro’s victory. After processing 80 per cent of the protocols, the incumbent won 51.2 per cent of the vote, while Gonzalez won 44.2 per cent.

The official result of 51% is “bad news” for the Chavistas in terms of eroding the social base. And for Maduro, getting 44% of the vote for the opposition candidate is a wake-up call, because if a more famous person had been in his place, he would have received even more votes. So, in this respect, the opposition can be congratulated on its victory, which essentially nullified Maduro’s political future, demonstrating a unity never seen before. However, it appears that the opposition does not need a hypothetical victory in the future, but a victory in the here and now. Therefore, as expected, it did not recognise the election results. Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado was the first to announce this. “Venezuela has a new elected president – and it’s Edmundo Gonzalez Urrutia, and everyone knows it. I want you to know that it was something so overwhelming, so wonderful that we won in all the states of the country,” Machado said, noting that according to the PUD headquarters, Maduro received 30 per cent of the vote while Gonzalez received 70 per cent.

The opposition leader called on all observers at the vote counting centres to remain in place because the platform will try to overturn the official results. Gonzalez said all possible norms of the electoral process were violated on 28 July. “Our message of reconciliation and change in the world is still relevant, and we are convinced that the vast majority of Venezuelans seek it. Our struggle continues and we will not rest until the will of the Venezuelan people is respected,” the presidential candidate said.

Meanwhile, Maduro celebrated his re-election for a third term with his associates with dances and songs at the Miraflores Palace, the official presidential residence. In his address to the nation, broadcast by local television stations, the president of the republic described the victory as a “triumph of peace and stability” and “ideas of equality.” At the same time, he said CNE’s electronic voting system had been attacked to accuse the ruling party of fraud.

As a result, the verbal altercation spilled into the streets. Thousands of opposition supporters took to the streets to protest in Caracas and other Venezuelan cities. According to the Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflicts, a total of 187 protests were registered in 20 states. The actions began on the evening of 29 July.

At first, so-called “caserolaso” demonstrations (march of empty pots and pans) began across the country, with participants banging pots and pans to protest President Maduro declaring himself the winner. The street protests then escalated into clashes with police. In the capital, security forces used tear gas and rubber bullets against protesters. In response, some protesters threw stones, flammable bottles and other objects at them. Colectivos, members of paramilitary organisations that support Maduro’s rule, helped disperse the protesters.

The opposition said Venezuelan security forces twice tried to break into the Argentine embassy in Caracas, where six of Maduro’s opponents have been living since March, after authorities decided to arrest them. Machado addressed the army and called for the overthrow of Maduro: “The people of Venezuela have spoken their word: they don’t want Maduro. It’s time to stand on the right side of history. You have the chance to do it right now,” the politician stated. However, the army has not turned its back on Maduro.

The number of law enforcement officers injured in protests after Venezuela’s presidential election has reached 77, one was killed, the country’s attorney general Tarek William Saab said. 1,062 people have been detained for taking part in the unrest. The number of protesters killed in clashes with security forces rose to 11 people.

The intensified internal escalation was accompanied by an international parade of recognition or not of the results of the vote in Venezuela. Washington was among the first to react to the official announcement of Nicolas Maduro’s victory. As U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken stated, the U.S. government is “gravely concerned that the announced results do not reflect the will or votes of the Venezuelan people.” A number of European countries, including Britain and Spain, joined the US in similar language. The EU and Brazil have demanded transparency in the counting of votes in Venezuela’s presidential election.

Leaders of several Latin American countries were even harsher in their assessments. “The Maduro regime must realise that the results are hard to believe …. Chile will not recognise any results that are not verifiable,” the country’s president Gabriel Borich wrote on social network X. “Argentina is not going to recognise another fraud and hopes that this time the armed forces will defend democracy and the will of the people,” Argentine leader Javier Milay said in the same social network, openly recognising Edmundo Gonzalez as the winner of the election. Similar formulations were heard from politicians of different levels in Peru, Costa Rica and Uruguay.

Argentina, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Guatemala called for an emergency meeting of the Organisation of American States (OAS) and a complete review of the Venezuelan election results. In addition, Peruvian authorities recalled the ambassador from Caracas and Panama suspended diplomatic relations with Venezuela. In response, Caracas decided to recall its diplomats from seven countries – Argentina, Peru, Panama, Chile, Costa Rica, Uruguay and the Dominican Republic. In addition, the country’s foreign minister, Iván Gil Pinto, demanded that these states remove their diplomats from Venezuela. According to him, these states, “subordinate to Washington”, are taking “interventionist actions” to which “Venezuela expresses its strongest rejection”.

The assessments of the representatives of the socialist states of the region, traditionally friendly to Caracas, were diametrically opposed, as if they were referring to completely different elections. In the interpretation of Bolivian President Luis Arce, the voting process in Venezuela was a real “democratic celebration” and Bolivians can only welcome the manifestation of “the will of the Venezuelan people at the polling stations”. Honduras, through its leader Ciomara Castro, sent its “special congratulations and democratic, socialist and revolutionary greetings to President Nicolás Maduro and the brave people of Venezuela for their undeniable triumph, which confirms their sovereignty and the historical legacy of Commander Hugo Chávez”.

Nicaraguan leader Daniel Ortega considered the outcome of the Venezuelan elections a “great victory.” Of course, on this occasion, warm words for President Maduro were not spared in Cuba. “Nicolas Maduro, my brother, your victory, which has become the victory of the Bolivarian and Chavista people, purely and unambiguously defeated the pro-imperialist opposition… The people have spoken, and the Revolution has won,” Cuban President Miguel Diaz-Canel addressed his Venezuelan colleague. Naturally, Moscow was not left out. Russian President Vladimir Putin congratulated Maduro on his re-election. In addition to Russia, China and Iran congratulated Maduro on his victory.

However, international pressure on Caracas after the first days of protests began to grow. It is noteworthy that even such a supporter of Nicolas Maduro as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban seems to have questioned his judgement. According to Politico, earlier this week Hungary blocked a joint statement from EU countries that questioned Mr Maduro’s re-election. However, Budapest then made it clear that it now supports the EU statement there: we were, they say, only “waiting to receive messages from Venezuela”.

Moreover, some individual representatives of Hungary went even further. In particular, Enikő Győri, a MEP from the ruling Fidesz party, announced the other day that she and her fellow MEPs in the European Parliament had signed a joint letter drafted by the far-right Spanish Vox party accusing Nicolás Maduro of a “huge fraud”. Even the left-wing president of neighbouring Colombia, Gustavo Petro, who has always had good relations with his Venezuelan counterpart, admitted that the election results were “seriously questionable” and called on the government in Caracas to “allow a transparent audit of the vote count and protocols with the participation of representatives of all political forces and international professional observers.”

The US also stepped up its pressure. Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Brian Nichols called on the Venezuelan president himself, as well as foreign governments, to recognise Edmundo Gonzalez as the winner. Later, Anthony Blinken, head of extra-political affairs, issued a similar statement, saying that the Venezuelan opposition’s vote counts show that Gonzalez “received the most votes in this election by an insurmountable margin.” Blinken’s statement did not threaten new sanctions on Venezuela, but he did hint at possible “punitive measures.” At least Reuters reported that Washington is considering new sanctions after the disputed election.

The US decision to recognise rival Maduro’s victory came at a time of comparative downturn in tensions between the two countries. In building a dialogue with Caracas between 2022 and 2023, the administration of US President Joe Biden was trying to solve several problems. One of them was to increase oil supply on the world markets. Against the backdrop of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, fuel prices in the United States were rising, and the historical peak of $5 per gallon of petrol was reached by June 2022 (in July 2024 prices fell to $3.5 per gallon).

The second goal is to reduce the rate of illegal migration from South America to the U.S., as Venezuela has become one of the countries in the region with the largest outflow of people in recent years. According to rough figures from the American Federation for Migration Policy Reform, U.S. Customs and Border Protection recorded 334,914 Venezuelan nationals entering the U.S. illegally in FY 2023, a 77% increase from 2022. However, the current U.S. stance on Venezuela is likely dictated by the domestic political interests of the Democratic Party. The move will be pitched by the Biden administration as a defence of democratic values and a show of force. This could give the party’s likely candidate for the November presidential election, US Vice President Kamala Harris, additional political points.

Under external and internal pressure, Maduro has asked Venezuela’s highest court to evaluate the election results. It was Nicolas Maduro’s first concession to opposition leaders, who have been claiming for the past few days that candidate Edmundo Gonzalez’s victory was stolen. “I surrender to justice,” the president announced outside the Supreme Court in Caracas, adding that he himself was “ready to be summoned, questioned and investigated” and that electoral authorities were ready to show all the vote-counting protocols.

Meanwhile, the president’s opponents are convinced that the demonstrative appeal to the Supreme Court was nothing more than a ploy that will ultimately make no difference. The Supreme Court is closely tied to the government, as all judicial nominations are made by federal officials and approved by the National Assembly, which is dominated by Mr Maduro’s supporters.

But the president has also found something to blame the opposition for. “We are now facing perhaps the most criminal attempt to seize power we have ever seen,” Mr Maduro, who in more than a decade in power has faced an attempt to challenge his rule not for the first time, told foreign journalists on Wednesday. Moreover, he openly said he hoped to see Edmundo Gonzalez and Maria Corina Machado in jail. “If you ask me … what should happen to the cowardly and criminal Gonzalez and a fascist from the criminal far right … named Machado, I will answer as head of state that there must be justice,” the Venezuelan president already told his supporters.

In addition, one of the narratives in Nicolas Maduro’s addresses to the public was the assertion that the attempt to remove him from power is part of a global far-right conspiracy, which involves such politicians and public figures as Argentine President Javier Milay, Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, the Spanish party Vox and the owner of the company X Ilon Musk (in short, all those who did not recognise the official election results).

The verbal altercation between Nicolas Maduro and Ilon Musk, who supported the Venezuelan protesters, was perhaps the most colourful. Following the first critical post on social network X of the American billionaire, the Venezuelan leader accused him of wanting to invade the territory of the republic and offered him to come to Venezuela to fight with him. Ilon Musk accepted the challenge, but with a condition: if he wins, Maduro will leave office, if he loses, the businessman will organise a free flight to Mars for him. “If I defeat you, Ilon Musk, I will accept your trip to Mars. But you will come with me,” the Venezuelan leader responded. However, the verbal pique of both did not end there. The last episode of this epistolary bickering was a new address of Ilon Musk to Nicolas Maduro in social network X, in which he promised to take the Venezuelan leader to Guantanamo prison on a donkey.

Washington’s recognition of Edmundo Gonzalez as the winner of the election spurred the opposition to new protests. Its leader Maria Corina Machado called for protests “in all cities” in the country to denounce Maduro’s controversial re-election. “We must remain firm, organised and mobilised, proud that we won a historic victory on July 28 and aware that for the sake of victory we will go all the way,” Machado wrote on social media. Machado is currently in hiding, fearing for his life.

Amid Machado’s calls, the heads of the US Congressional Foreign Affairs Committees and the chairmen of the foreign affairs committees of several European countries threatened Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro with liability if he did not leave office. According to a joint statement by the officials, Venezuelan authorities must stop “the brutal repression of Venezuelans and the persecution of opposition leaders.” Negotiations between Messrs Maduro and Gonzalez should be held to “ensure a peaceful and democratic transition of power”, the statement said. “Our governments are closely monitoring the situation in Venezuela and will work together to hold Maduro accountable if he continues to ignore the democratic will of Venezuelan voters to steal another election,” the document said. It was signed by Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Ben Cardin, House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Michael McCaul and the chairmen of the Foreign Affairs Committees of Armenia, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Poland, Romania and Ukraine.

After several days of anxiety that left the streets virtually deserted, normal life has begun to resume in the capital, Caracas, with shops opening and public transport running. Of course, the future course of events will largely depend on the strength of the protest movement inside the country, on the one hand, and on Maduro’s actions, on the other. If he manages to “calm” the society without a “bloodbath” and the appearance of a large number of political prisoners, it is possible that he will have a chance to stay in power. In case he follows the path of repression and fails to keep the situation under control, his regime will most likely be swept away.

Either way, much is in Moduro’s hands at the moment. During Venezuela’s last presidential election in 2018, protests lasted for months, but the power of Maduro and his United Socialist Party held firm. How it will be this time and in what scenario the situation will develop we will know, probably in the near future.