On 15 July, 9.7 million Rwandans went to the polls to vote in the general elections: for the president of the country, as well as 53 of the 80 members of the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of parliament, and the following day the remaining 27 deputies, with quotas for women, youth and people with disabilities.

However, Parliament is not the main actor in the country. Rwanda is a presidential republic and its policies are determined by the head of state, so the key question here is who will be the head of state. However, for this African country it is a rhetorical question. As it was known to almost everyone that 66-year-old Paul Kagame, a native of the Tutsi people and the eighth president of Rwanda since 2000, would become the president of Rwanda for the fourth time.

And all the intrigue was just about the percentage he would gain. In 2003, 2010, 2017 respectively, Kagame scored 95.05%, 93.08%, 98.63%.

In this piece Ascolta analyses the results of elections in Rwanda – a small, but extremely important African country, which has a tangible influence on political processes on almost the entire African continent. The piece also analyses the possible prospects and consequences for the country against the background of another re-election of Robert Kagame.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

The elections almost coincided with a round date – the 30th anniversary of the coming to power of the ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front, to which Kugame is directly related. He was at the origin of this politico-military organisation, which was founded in 1988 in Uganda by Rwandan emigrants and comprised Tutsis and moderate Hutus. In 1990, the RPF, then effectively led by Kagame, crossed into Rwanda and launched an offensive against the Rwandan government. The Arusha Agreement signed in 1993 suspended hostilities.

However, in April 1994, Rwanda witnessed one of the bloodiest episodes in twentieth-century human history, the genocide of the Tutsi people and moderate Hutus. Human Rights Watch estimates that between 6 April and mid-July 1994, at least 500,000 people were systematically massacred (with firearms, machetes and sticks with nails) in Rwanda over a period of about one hundred days. However, estimates of the number of victims have increased and reached figures of around 800,000 or even a million.

It is worth recalling that the genocide began after a plane carrying Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu who was the president of Rwanda at the time, was shot down over the country’s capital. Within the first 24 hours, Colonel Theoneste Bagosora, who seized power, with the help of the Presidential Guard, massacred all Hutu opposition in the government. The RPF, led by Paul Kagame, resumed its offensive and in a short time was able to completely seize power in the country. After the RPF entered the capital Kigali in July, the genocide was brought to an end. A coalition government comprising Tutsis and Hutus was formed, with moderate Hutu Pasteur Bizimungu as president and Kagame as vice-president and defence minister. Many Hutus fled to neighbouring Zaire (DRC), prompting a shift in fighting outside Rwanda. Kugame supported the military rebellion in Zaire led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, which led to the overthrow of the dictatorial regime of Mobutu Sese Seko and the assumption of power in Zaire by Laurent-Désiré Kabila. At the same time, Zaire was renamed the Democratic Republic of Congo. We will talk more about how relations between the countries developed and why they are so important for Rwanda.

For now, let’s focus on the presidential elections and their results and try to answer the question: why Paul Kugame became for the fourth time the president of Rwanda and gained a record 99.15% (!!!) of the electoral support.

Non-alternative elections

It should be said that today’s election of Paul Kugame, purely procedurally was possible thanks to the referendum of 2015, which amended the Constitution: the document stipulated that the head of state can be re-elected only once. At the same time, the decision of the 2015 referendum nullified the two terms of his presidency, and now he can remain in power until 2034. Well, it is quite a working scheme for autocrats. In Russia, the Constitutional Court also nullified Putin’s presidential term in 2020, and now he can be re-elected until 2036.

The election campaign itself was not much different from previous ones, except for the decision to hold parliamentary and presidential elections on the same day, which had absolutely no effect on the actual balance of power. It was also the first election in which people born during Kagame’s presidency reached voting age. The same three politicians contested the election as in the previous one seven years ago. Besides Kagame – Philip Mpayimana, 54 – an independent candidate, a journalist by profession. Fled Rwanda for Europe during the genocide, returned just before the 2017 elections – in which he got 0.73 per cent of the vote. Says that after spending 18 years in exile, he “witnessed Rwanda’s journey towards transformation and wanted to be part of that development.” Mpayimana attributed his repeated participation in the election to “seeing Rwanda’s potential”.

“When you look at Rwanda’s progress, you see that the country is on the way to a better transformation. Those who look at it differently only see the lack of democracy and the worst side of Rwanda, but I want to make sure that Rwanda continues on this positive path and does not deviate from it because I know that I can and want to make sure that it stays on this path,” he told a press conference on 9 July. The politician accused Belgium, Germany and France of distorting history and influencing the morale of Rwandans since 1894, which eventually led to genocide, and announced that he would file a lawsuit against them at the International Court of Justice in The Hague.

Frank Habineza, 47, is the leader of the Democratic Green Party, founded in 2009. In 2010, after his deputy was assassinated, fled to Sweden; obtained Swedish citizenship but renounced it before the 2017 elections. At that time he got 0.48 per cent of the vote. In the 2018 elections, he and his associates won seats in parliament, becoming the first opposition force to get there. In an interview, he said his party had learnt from past experience and strengthened itself. “In the last elections, for example, we lacked women and youth structures at the constituency level. However, this year we have managed to create them. In addition, our party now has three parliamentarians – two in the lower house and one in the senate. We also have people in the local administrative councils. We as a party have become stronger than we were before,” he assured.

Analysts, however, gave these candidates little chance of winning, noting that both Habineza and Mpayimana are unrecognisable and have limited financial and organisational resources to seriously challenge Kagame. In fact, their main objective appears to have been to show that Kagame has competitors and that the elections are being held on a democratic alternative basis.

But those who would have posed even the slightest threat to Kagave did not get on the ballot papers. For example, the National Electoral Commission did not allow Kagame’s long-time critic Diana Rwigara of the Movement for the Salvation of the People to participate in the elections, saying she had not properly completed the paperwork. In 2017, she too was barred from the election because of allegations that she forged signatures of her supporters. She was arrested on charges of forging documents and inciting subversion of state power and kept behind bars for over a year.

Rwigara is the daughter of Assinapola Rwigara, an industrialist and former major donor to Kagame’s ruling Rwanda Patriotic Front party before he fell out with its leaders. Incidentally, Assinapola Rwigara is not Kagame’s first “friend” with whom he has fallen out. This includes Kayumba Nyamwasa, a close friend of Kagame with whom they were founding members of the Rwanda Patriotic Front. Today, the politician lives in exile in South Africa, having fled the country due to persecution by the regime. His disillusionment with Kagame began in the late 90s when he and his allies marginalised the first president, the moderate Hutu Pasteur Bizimungu, to come to power, and later also jailed him.

Nyemwasu witnessed Kagame earlier beating up his counsellors demanding blind obedience. According to him, Kagame is a boss from hell who rules through fear, trying to control not only all branches of government but also private businesses. Kagame’s intensifying dictatorship, his intolerance of dissent and competition has been growing the list of his former comrades-in-arms who have died and fled the country. In 2014, the year of the third attempt on Nyamwasa’s life, Patrick Keregeya, another former comrade of Kagame’s and former head of intelligence, was found strangled in a Johannesburg hotel.

During Kagame’s rule, some dissidents and critics were imprisoned, others died or suspiciously disappeared. Naturally Rwandan officials have long denied the allegations of wrongdoing, only noting that Rwandan politics are still shaped by the tragic legacy of the 1994 genocide, and so it is not yet time for policies that “tend to create divisions.”

“It is worrying that the ruling party has taken increasingly harsh measures over the years and that the threshold for criticising it is getting lower and lower,” said Clementine de Monjoy, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch, who was prevented by authorities from entering Rwanda earlier this year. The country is also labelled “unfree” in the latest Freedom in the World report, which tracks global trends in political rights and civil liberties, with a score of 23 out of 100. The report by the non-profit organisation Freedom House said key problems in the country include a lack of free and fair elections, a lack of opportunities for the political opposition to campaign, a lack of free media and an independent judiciary.

Domestically, Kagame has outlawed the opposition. Two other opposition members Victoire Ingabire and Bernard Ntaganda were also rejected by the National Electoral Commission because of past, unexpunged criminal records, which they incidentally received for their opposition views. Ingabire challenged Kagame back in 2010 and spent eight years in prison. Kagame released her early and banned her from leaving Rwanda. Thus, the removal of opposition leaders from the presidential race has made them virtually unopposed and uncompetitive.

But it is not only the mopping up of the political field that allows Kagame to win elections with record results. Recall that in the July 15 elections, Paul Kagame garnered 99.15 per cent support from the electorate. While his opponents Frank Habineza of the Democratic Green Party got only 0.53 per cent of the vote while independent candidate Philip Mpayimana got 0.32 per cent. “The results presented show a very high appreciation, these are not just numbers; even if it was 100 per cent,” Kagame said in a statement from the headquarters of his ruling Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) party. “These figures show confidence and that is the most important thing.” There are probably plenty of reasons for the opposition to believe that Kagave’s high results are a consequence of electoral fraud. But still, these figures also reflect another side of the coin – Kagame is popular.

The best man in the country

During this election campaign, however, as in previous years, Kagame’s rallies attracted tens of thousands of people, while his opponents tried to gather participants for their events on crumbs. Kagame’s supporters deify him, believing him to be the best administrator this East African country has ever had. He is credited with uniting the country and providing security for Rwandans. Kagame’s government rebuilt institutions that had been destroyed or even never existed: ministries, police, civil service and most importantly, held a national dialogue that created the basis for modern Rwanda.

One of Kagame’s major achievements is economic progress, although some critics say the government manipulates statistics to embellish the president’s image. Between 2000 and 2017, the country’s GDP almost quintupled (from $1.7bn to $8.4bn) and economic growth has consistently stayed below 6%. Rwanda is known as Africa’s first smartphone manufacturer and even as Africa’s space industry leader. Over the past few years, Rwanda has positioned itself as a “test lab” for companies interested in introducing products and services developed for Africa.

For example, Volkswagen has opened a small assembly plant; BioNTech is building a vaccine manufacturing facility; Qatar Airways Group is in talks to acquire a 49% stake in national carrier RwandAir as Kugame seeks to turn Kigali into Africa’s tourism hub. Apart from tourism, which has grown significantly, much attention is being paid to marketing and promotion of the country. The Visit Rwanda campaign, for instance, has sponsorship contracts with football clubs Arsenal and Paris Saint-Germain worth $30 million each. Kigali is second only to Cape Town in Africa in terms of conference and meeting venues.

Rwanda has also made some progress in the social sphere. Life expectancy has risen from 47.1 to 66.4 years, and child mortality has fallen sixfold. However, despite economic progress and visible brilliance, the country is still quite poor. Two-thirds of Rwandans still work in agriculture, nearly 40 per cent of the population lives below the poverty line, a fifth are food insecure and nearly a third of children under 5 are chronically undernourished.

But it cannot be overlooked that petty crime is non-existent in the country. On the last Saturday of every month, people all over the country go out for Umugande, a compulsory cleaning exercise in their communities. Therefore, Rwanda is a clean, well-maintained country where no one demands bribes from either tourists or businessmen, which is confirmed by world rankings on the Corruption Perception Index. Foreign investors claim that asphalted roads and reliable power grids testify that the allocated capital investments are spent for their intended purpose and not in the pockets of ministers.

Strict control and outward signs of progress have led to another cliché: Rwanda is the “Singapore of Africa”, which fits Kagame’s vision of the country’s economic model. The president’s immediate goal is to turn Rwanda into a middle-income country with a per capita income of at least $1,035 according to the World Bank’s classification. Today it is already about $1,000. As experts note, Kagame’s policy is market-friendly, which distinguishes Rwanda from the policies of its neighbours. The emphasis is not on soliciting aid, but on creating an attractive investment climate to attract foreign investment. Kagame therefore needs internal stability and clarity in the functioning of all state institutions. The Rwandan president demands that officials strictly fulfil their tasks and personally supervises them.

Once a year Paul Kagame hosts a national television programme -Umushykirano, which translates as the National Dialogue Council. This unique spectacle, which attracts millions of viewers, resembles the ritual opening of a box of people’s complaints. Kagame gathers politicians, high-ranking civil servants in a conference room in Kigali and then gives them a “public flogging” on their areas of work based on complaints sent through social media or from conference rooms across the country by the people of the country. It must be said that Kagame criticises real shortcomings in the work of the authorities, not invented for show. And he does so in an emphatically harsh and insulting manner. Umushykirano serves as an annual reminder to officials of Kagame’s power and the two sides of the same coin that helped him retain that power: a ruthless focus on efficiency, laced with a hefty dose of fear.

It is worth noting that Kagame’s power rests on another powerful pillar – the Rwandan Patriotic Front, which is not just a political party but Rwanda’s largest taxpayer and employer. The fact is that the RPF runs the country’s economy through its own holding company, Crystal Ventures LtD (CVL), which was set up in 1995 as a relief and reconstruction fund for the devastated country. Over the years, it has grown into an extensive investment conglomerate controlling the food and beverage industry as well as businesses such as telecoms, logistics, banking and the security services market. Thus, it directly or indirectly controls a significant portion of the most profitable assets in the economy, including the NDP’s largest engineering and construction company, and serves as a market entry point for foreign businesses that are offered partners with its subsidiaries.

In addition, the holding company finances party work and election campaigns, and is also a kind of “incubator” for future political and business managers. In 2021, Crystal Ventures LtD has a foreign division – Macefield Ventures, which has branches or stakes in companies in at least 5 African countries (Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Republic of Congo and CAR). CVL is often accused of unfair competition, winning the majority of government contracts and monopolising. Its main competitor, Horizon, a company controlled by the Ministry of Defence, often acts in tandem with CVL.

Turning chaos into order and money

It is not only economic success or mopping up the political field that pays electoral dividends for Kagame. Rwanda’s foreign policy is the most important tool for consolidating his political authority. It can be divided into three directions – relations with Western countries, the African track and the Eastern vector, primarily China and Russia.

Over the last decade, Paul Kagame has become the West’s most important ally in Africa, and as some experts and journalists ironically say – its favourite autocrat.

Rwanda’s army is the UN’s chief peacekeeper and protects both foreign energy projects and African presidents. France is indebted to Kagame for the contribution that his armed forces, as a peacekeeping contingent, played in bringing order to the Central African Republic and Mali, former French colonies. The Rwandan peacekeepers based in Mozambique are playing an important role in the fight against the Islamic State jihadists who, through their actions, have delayed for several years the realisation of the $20 billion TotalEnergies French project.

The project is a liquefied natural gas plant that was frozen in 2021 after jihadists raided the town of Palma, killing more than 800 people. Since Rwandan peacekeepers began operations in Mozambique they have returned about 90 per cent of the country’s territory to government control. The TotalEnergies project is seen as a future source of fuel for the EU and has become even more important after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine paralysed the supply of blue fuel to Europe. The EU has therefore, for the first time in its history, directly financed not only the presence of the Rwandan Defence Force in Mozambique, but also the additional deployment of 2,000 more Rwandan troops and the associated supply and logistics costs.

The UK, another influential Rwandan ally, owes Kagame a debt of gratitude for a variety of reasons. When the Conservative Party was still in power, one of its domestic policy priorities was to tackle irregular migration. In 2022, Kigali signed an agreement with London to bring all asylum seekers to Rwanda. This agreement provoked a lot of negativity from human rights activists and opposition politicians. However, not a single migrant has yet to be deported to Rwanda, but London has already paid Kigali £140 million for his co-operation.

In March this year, British Home Secretary Suella Braverman travelled to Kigali to visit two housing estates for migrants and told reporters that deportations could begin by the summer. Kagame had another staunch friend in the Conservative government in the person of Sunak Minister of State for Development and Africa Andrew Mitchell, who has made no secret of his admiration for the Rwandan leader. Britain’s new Prime Minister Keir Starmer will have no such admiration for Kagame. A few days before the election, he said the disgusting deal with Rwanda on “money for asylum seekers” was “dead and buried”.

Russia’s active penetration of the “black continent”, especially the activities of PMC Wagner, has awakened Washington’s interest in cooperation with the Rwandan Defence Force. However, despite this, unlike France and Britain, which turn a blind eye to Kagame’s authoritarianism, the U.S. is more harsh in its criticism of the Rwandan regime. Washington is particularly concerned about the state of human rights in the African country, in part because of the treatment of human rights activist Paul Rusesabagina, a US resident who was sentenced to 25 years in prison in Rwanda in 2020. Thanks to U.S. pressure, Rusesabagina was released, removing a key bone of contention between Washington and Kigali and raising again the question of whether the Biden administration will continue to push Kagame to withdraw troops from Congo.

Underlying the West’s concern over Rwanda’s destabilisation of Congo is the realisation that Russia – whose Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov visited Africa twice within ten days in early 2023 – is aggressively forging new friendships on the continent. Of the 39 nations that either abstained or voted against the UN General Assembly resolution condemning Russia’s aggression against Ukraine – 17 were African. So the US, like other Western countries, wants to encourage African countries threatened by Islamist insurgencies to turn to Rwanda and its disciplined peacekeepers for help, rather than to Russia and its infamous Wagner Group mercenaries. To this end, they spare no “perks”. Last year, Kagame became chairman of the Commonwealth of Nations, which is made up of former British colonies, although Rwanda never was. And his foreign minister is head of the International Organisation of La Francophonie, the French equivalent of the Commonwealth.

As for Rwanda’s relations with African countries, Paul Kagame is the continent’s chief pan-Africanist. He has become the personification of the slogan “African solutions to African problems”. However, in some cases he does not solve them, but only creates them. I am referring first and foremost to relations with the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The roots of the conflict are rooted in long-standing grievances, and unclosed gestalts are becoming more and more fatal with each passing year.

In order to understand the causes of the conflict, it is necessary to go back to 2012, which turned out to be a fateful year for the region, because it was then that a group emerged that became one of the main actors in the conflict: M23, or the 23 March Movement. Former soldiers of the Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, a political movement created in eastern Congo in 2006, composed mainly of Congolese Tutsis, with the support of Rwanda and Uganda, rebelled against the DRC government and President Joseph Kabila, accusing him of discriminating against Tutsis.

In November, M23 fighters reached and occupied Goma, the largest city in eastern Congo. In just a few weeks of armed conflict, more than 140,000 people were internally displaced. The death toll was rising, and resolving the conflict required international intervention. Thanks to regional diplomacy, particularly mediation by the Southern African Development Community (SADC), as well as military pressure from the UN contingent, the Rapid Intervention Brigade, specifically created to combat armed groups, the rebels were defeated by the end of 2013. Most M23 members retreated to Rwanda and Uganda. The remainder either voluntarily demobilised or dissolved into the armed forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), but these were few in number. In early 2017, several hundred Ugandan M23 fighters fled to Congo, where there were a series of clashes with Congolese armed forces – which, however, were sporadic and did not appear to be dangerous to local authorities.

Kagame was then “cooled” by the U.S. and other Western countries, which responded by cutting financial aid to Kigali and threatening to sanction Rwandan officials for aiding and abetting war crimes. This unified international response forced Rwanda to stop supporting the rebels and played a key role in the rebels’ defeat.

Congo-Rwanda relations then experienced something of a honeymoon period, with leaders from both countries exchanging words of mutual respect and the Rwandan army conducting operations against the FDLR in eastern Congo with the blessing of DRC President Tshisekedi. Kagame even attended the funeral of Tshisekedi’s father, Etienne, a seasoned politician known for his longstanding opposition to Mobutu. However, the nascent friendship soured. The occasion appears to have been the signing in May 2021 of a surprise agreement between Tshisekedi and Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni that allowed Uganda to move heavy mechanised equipment into northeastern Congo to clear sections of equatorial forest and repair some 140 miles of road, An infrastructural upgrade that was expected to boost cross-border trade, both legal and illegal, eliminating the need to transport goods through Rwanda.

Six months later, Ugandan troops entered Congo to neutralise another rebel group, known as the Alliance of Democratic Forces, which was using the region as a base. The two initiatives appear to have both frightened and infuriated Kagame, who saw them as part of a joint attempt by Tshisekedi and Museveni to push him back economically and strategically. In April 2022, Congo joined the East African Community, reinforcing the impression that Tshisekedi, who once seemed intent on earning Kagame’s favour, was now acting over Rwanda’s head to engage directly with other East African leaders.

Kagame’s response was not long in coming. On 12 November 2021, after years in dormant mode, M23 launched another offensive – around the villages of Chanzu and Runyonyi in North Kivu. In just a few weeks, the rebel army reaches the foot of the Nyiragongo volcano – less than 30 kilometres from Goma – and by March 2022, M23 rebels had captured most of Rutshuru, bordering Uganda and Rwanda. In May, they occupied Rumangabo military base, the largest military installation in North Kivu. The main M23 force then moved south towards the provincial capital of Goma. In June, another M23 unit marched north and occupied the border town of Bunagane, forcing Congolese soldiers to flee to Uganda.

All of this came as a surprise, given the decade-long absence of M23 activity. The rapid advance of M23, which made headlines around the world, puzzled even international observers. There were theories that it was not without someone’s help. A report by a group of UN security experts notes that the rebels are as well armed and equipped as a good regular army. Someone is supplying them with night vision devices, modern assault rifles and machine guns. DRC President Felix Tshisekedi himself echoed the report and directly named the “sponsor” – Rwanda.

Experts noted that the revival of the M23 in eastern DR Congo in November 2021 occurred at the same time as Uganda’s armed forces appeared in the region. Ugandan soldiers entered North Kivu province with the authorisation of Felix Tshisekedi to pursue the Islamist group Alliance of Democratic Forces (ADF). At the same time, Ugandans were authorised to secure roads in eastern DR Congo, the construction of which Uganda began in December 2021.

On 8 February 2022, Paul Kagame delivered an angry 50-minute speech to the Rwandan parliament denouncing the threat to national security posed by the Congolese provinces of North and South Kivu. Paul Kagame flatly denied that Rwanda had armed the group that had emerged near its borders. The M23 themselves claim to have found the weapons in mines, where they were stored when they retreated in 2013. The Rwandan leader emphasises that all M23 members are citizens of DR Congo and that the reason for their rebellion is DR Congo’s internal problems, including violations of the rights of the Kinyarwanda-speaking population. While denying his involvement in supporting M23, Paul Kagame has sought to shift the attention of his critics to another rebel group, the Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda, known by its French acronym FDLR. It was founded more than two decades ago by soldiers and militiamen from the Hutu ethnic group that fled to Congo and was responsible for the 1994 genocide.

According to Kagame, the group remains an existential threat to Rwanda. The FDLR has long become a bogeyman whenever Rwanda’s interference in Congo’s affairs has been criticised by the world community. On the eve of the events of the 2021 conflict, Rwandan officials played the FDLR card incessantly, refrain being that a second genocide was imminent, this time targeting not only the Tutsis living inside Rwanda, but also those living across the border in Congo.

According to Kagame, the danger emanating from them is so high that he is considering deploying troops in DR Congo’s eastern region without the approval of Felix Tshisekedi. “Because we are a very small country, our current doctrine is to go where there is fire and put out the fire. We will fight the war where it started and where there is enough space to fight the war… We are doing what we have to do, whether or not there is consent from others,” Paul Kagame said.

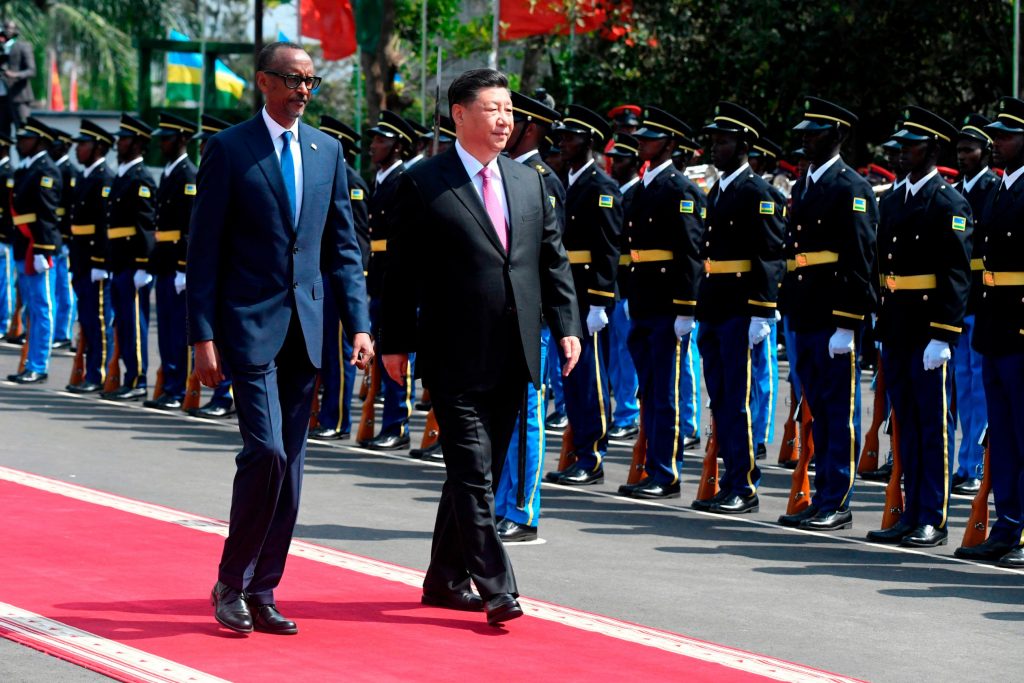

Photo 7

It must be said that no one but Kagame’s supporters believed in Kagame’s pathos-laden words. Rwanda’s unrecognised exploits in Congo have long since ceased to be self-defence or even revenge. A key driver of the latest crisis was Rwanda’s rivalry with Uganda over control of resource extraction in DR Congo. This country, comparable in area to Western Europe, has the world’s largest reserves of cobalt, germanium, tantalum and coltan, as well as significant deposits of coal, iron, tungsten, copper, zinc, tin, beryllium, lithium, manganese, oil, diamonds and gold.

Up to 90% of Congo’s gold production is smuggled into neighbouring countries, with the lion’s share arriving in Rwanda and Uganda. Both countries declare gold as one of their largest sources of foreign exchange, although neither country produces the precious metal in large quantities. As both Uganda and Rwanda need access to the eastern DRC to fuel their economies. Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi is faced with the difficult task of finding a balance. Experts say Ugandan authorities expressed irritation after Felix Tshisekedi signed an agreement with Paul Kagame in June 2021, giving the Rwandan company rights to refine gold mined in DR Congo. In turn, Kagame was angered by Uganda’s massive road-building project in DR Congo.

However, the thirst for minerals alone does not explain what is happening in North Kivu today. The area now controlled by the M23 contains several important mines, and the fighting has disrupted smuggling activities if anything. The real reason Kagame revived M23 – and risked both his carefully cultivated image as an African statesman and Rwanda’s reputation as a business-friendly, development-oriented state – is his thirst for recognition as the region’s most important player. By renewing his support for M23, Kagame is reminding the leaders of neighbouring countries of his willingness and ability to destabilise the entire region if any attempt is made to leave him out. “Ignore me at your peril” is the subtext of the mutiny.

The M23 mutiny has certainly put the brakes on Uganda’s plans in eastern Congo. After the M23 captured the Congolese border town of Bunagana last June, Ugandan authorities were forced to withdraw road-building equipment and suspend plans to upgrade 55 miles of road linking the border outpost to Goma. The impact of the rebellion is even more devastating in Congo. Backed by the Congolese army, dozens of disparate Congolese militias that once had little in common are putting aside their differences to fight what they see as an invading force backed by Rwanda. And with so many African countries embroiled in the conflict and so many fighters with guns hoping to profit, the balkanisation of Kivu and the destabilisation of the wider Great Lakes region became real possibilities. Subsequent events have shown that the DRC has become a powder keg that could explode at any moment. And Kagame has enough will and perseverance to put a burning match to the fuse when necessary.

It must be said that Belgium, France, Germany, Spain and the US, as well as the UN and the EU, have called on Rwanda to stop supporting M23. However, personal interests have so far prevented many of them from using the economic leverage that worked in 2012. During a trip to Kinshasa, French President Emmanuel Macron pledged 34 million euros in humanitarian aid to eastern Congo, but seemed determined not to blame Rwanda for the violence there and emphasised that any sanctions would have to be postponed until peace talks were concluded.

“Appeasement” of the aggressor by the West is increasingly unleashed on Kagame. He likes to repeat that his main ally is the Rwanda Defence Force, which has become the third largest peacekeeping force in the UNPO. And because they are arguably the best-trained army in Africa it is often invited to intervene in crises across the continent. This innovative strategy by Kagame firstly protects Rwanda from criticism from Western states as it defends their interests in places where they themselves will not go, and secondly, and of particular importance to Kigali, to ensure the economic expansion of Rwandan campaigns in neighbouring countries.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the mineral-rich Central African Republic. Kagame’s troops are not only protecting the CAR president, keeping him in power and fighting local rebels. Rwanda’s military presence protects its commercial interests. The fact is that 100 miles southwest of the CAR capital, Bangui, are mines where dozens of Rwandan miners in open pits under the protection of Rwandan soldiers extract gold and diamonds.

Rwanda’s economic presence in CAR has extended far beyond the mining complex. According to the CAR’s Ministry of Commerce, there are 119 Rwandan-owned businesses in natural resource extraction, food production, construction, transport, and banking. Rwanda’s military presence has opened the door in CAR for the well-known party holding company Crystal Ventures LtD (CVL). Its subsidiary mining company has five gold and diamond concessions in CAR, and more recently CVL management has been in discussions with government officials about possible projects in agribusiness and food processing.

Kagame’s “guns then profits” model is working in Mozambique as well. We have already highlighted how Kagame sent 1,000 Rwandan soldiers to the Kabu Delgadui region in 2021 to save a $20bn gas project run by French giant Total. But there is another side to this coin. By being credited for saving the costly project it has ensured the penetration of Rwandan businesses into the region. So subsidiary Crystal Ventures LtD campaigns there in mining, construction, security services, opens shops and is involved in tenders related to the Total plant. “Wherever his soldiers go now, the business follows them – it’s as simple as that,” David Himbara, who was Kagame’s private secretary and then head of strategy before becoming his critic and fleeing the country for Canada, notes in an interview with Bloomberg. “Soldiers make money, and he enhances his reputation as a world leader.” – adds Khimbara. By relentlessly raising the stakes, Kagame makes it impossible for his fellow African heads of state or his Western allies to ignore him. Moreover, by occasionally looking in the direction of Beijing or Moscow, he makes them even more accommodating.

His 99.15 per cent victory in the presidential election is unrivalled even among the most undemocratic countries. Russian President Vladimir Puti won 88.4 per cent in the March elections. Naib Bukele of El Salvador, who is called “the world’s coolest dictator”, scored 85 per cent in the February elections. And Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev secured his fifth consecutive term with 92 per cent.

But behind Kagame’s electoral record, many analysts in Africa and the West saw a frightening march of repression and increasing authoritarianism. Only a short time ago, he was receiving nothing but praise from abroad and claimed to be Africa’s most successful and inspirational leader of the 21st century. And for good reason: Kagame led the country out of civil war and the horrific genocide of 1994. More than two decades of economic growth followed, making Rwanda Africa’s most dynamic country. Its social stability has become the envy of many African countries.

Now the West faces a dilemma: accept the Rwandan model of “democracy” with all its consequences and allow Kagame to continue, using its army, to protect their business interests on the “black” continent. Or condemn Kagame’s authoritarianism, human rights violations and all his repression, and thus perhaps push him into the even tighter embrace of China and Russia, who already control Africa much more successfully than, for example, the US and France.

Paul Kagame himself seems unlikely to want to change his system of governance, especially with such enormous popular support. Will the West be able to influence this and steady the tilting Rwandan ship of democracy? This is hard to believe, although in our tough world we know how to make offers that are hard to refuse.