As the election campaign in Europe drew to a close, three parts of the world – Africa, North America and Asia – were already taking stock of their elections. More than 800 million people went to the polls in India, Mexico and South Africa. This factor and the role of the countries themselves in global politics determined their importance for the whole world, and the results recorded the emergence of new political trends that will be taken into account by the main geopolitical players. Let us focus on the features and the most important political lessons of the campaigns.

In this material Ascolta analyzes the results of election campaigns in three countries at once – South Africa, Mexico and India, where a total of one seventh of the world’s population was involved. The article studies not only internal political processes in these countries, but also possible trends and forecasts affecting geopolitical processes.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

A bloody Mexican soap opera

On June 2, general elections were held in Mexico, the largest in the country’s history. About 100 million voters chose not only the president of the country, but also 500 deputies of Congress, 128 members of the Senate and almost 20 thousand officials in various positions in the regions, including the mayor of Mexico City and nine state governors.

A large-scale election campaign has become the bloodiest in the country’s history. Between September 2023 and April 2024, nearly 400 Mexican politicians and journalists were targeted by criminal organizations, according to local consulting firm Integralia, including threats, kidnappings and even murders. The country’s Minister of Security and Citizen Protection, Rosa Isela Rodriguez, reported that 22 candidates in local elections were killed during the campaign. The Mexican publication El Universal cited an even higher figure of 37 people.

Cartels and other criminal groups see elections, especially local elections, as an opportunity to seize power. Violence was particularly high in states where cartels are fighting over territory – Chiapas and Guerrero in the south and Michoacán in central Mexico. On May 29, mayoral candidate Jose Alfredo Cabrera Barrientos of Coyuca de Benitez (Guerrero state) was shot and killed during his final campaign meeting with voters. The New York Times notes, however, that a sharp rise in election violence is not unusual in Mexico. According to security consulting firm Integralia, 36 candidates have been killed during the 2021 midterm elections. Current President Obrador has also claimed that the ongoing violence during the campaign was the result of links between previous authorities and criminal gangs. However, many Mexican analysts note that the surge in violence was the result of López Obrador’s policies, characterized by the slogan “Abrazos, no balazos” (Spanish for “hugs, not bullets”) and emphasizing addressing the social causes of violence. In the end, however, cartels and other criminal groups only expanded their influence.

Mexico is moving away from political tradition

It is clear that against the background of the general elections, the main attention was focused on the presidential elections. And it must be said that Mexico surprised and even set several records. Even during the election campaign it became clear that the country, where only men have been ruling since the XIX century, would change the gender of the president. At the time, Mexican media wrote that electing a female president would be a big step forward for a country with high levels of gender violence and deep inequality between men and women. As the media noted, machismo, which has created economic and social inequality, is still relevant in Mexico. Women’s representation in government remains low, and misogyny in its most extreme form is manifested in the high number of murders and acid attacks against women.

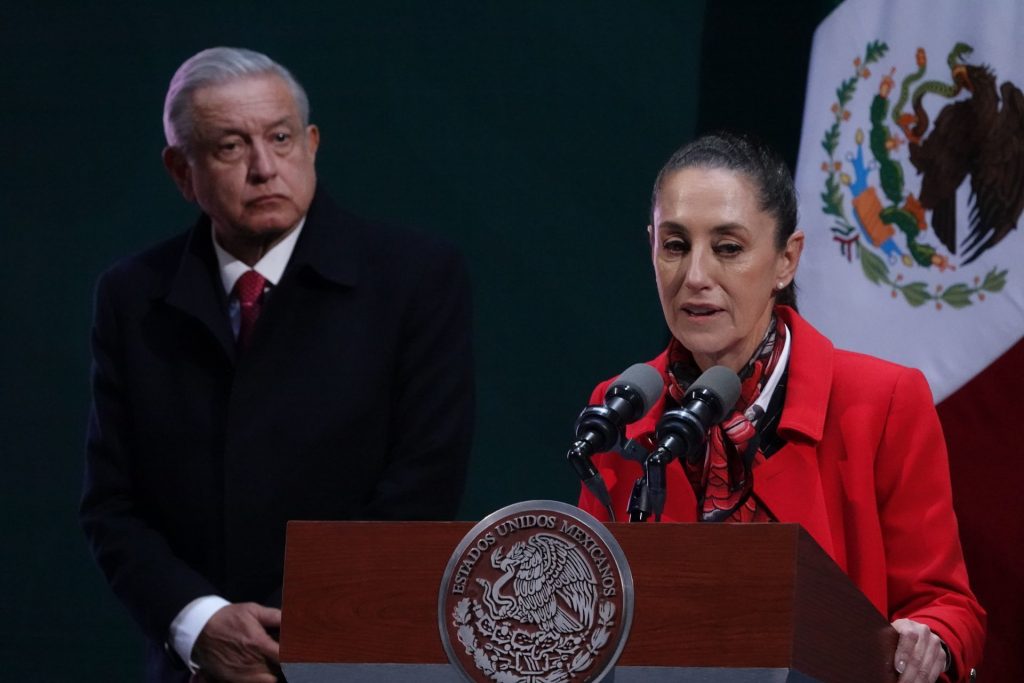

The election resulted in the presidency of Claudia Sheinbaum, 61, a former Mexico City mayor and climate scientist who went to the polls from the pro-government National Revival Movement (Morena) party of the center-left Sigamos Haciendo Historia (“Let’s keep making history”) bloc. She broke several records. First, by becoming Mexico’s first female president. And also becoming the first Mexican president of Jewish descent and the first woman to win the general election for the highest office in North America. Mexico thus surpassed the United States and Canada in this component of gender diversity.

Sheinbaum is described as a protégé of current Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador. She is often criticized for her “absolute loyalty” to her boss: according to The New York Times, many believe that she will not be able to make decisions independently and will “call him every day”. Sheinbaum herself, however, calls such claims “sexist and misogynistic.” Lopez Obrador, 70, who has led the country since 2018 has won the support of a broad cross-section of the population, including the working class as well as voters from low-income villages who felt forgotten in the political system. Socialist Obrador initiated many social programs. Although many of them remained on paper, the people of Mexico saw that he was trying to do something.

However, as the Associated Press notes, Lopez Obrador’s attacks on the judiciary and the expansion of military rights he initiated have drawn widespread criticism from human rights activists. With a 60% approval rating, Obrador did not run for office. The country’s constitution prohibits the president from running for a second term.

Sheinbaum – no alternative

Claudia Sheinbaum is the granddaughter of Jewish immigrants who fled Europe. She grew up in Mexico City. While studying at the National Autonomous University, she led a movement protesting tuition increases and changes in admission conditions. Sheinbaum first gained fame as a physicist. In 2000, López Obrador, then mayor of the capital, appointed her in charge of environmental protection. In 2007, Sheinbaum became one of the collective winners of the Nobel Peace Prize as a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Sheinbaum has a doctorate in energy and has authored more than 100 articles and two books on environmental topics. For a long time, she has combined academia and politics. “I grew up believing that politics can change the world along with academic and scientific approaches,” she stated.

“In 2014, when López Obrador founded his Morena party, he asked her to run on the party ticket for mayor of Tlalpan, a Mexico City neighborhood. It was also thanks to his support that she won,” The New York Times wrote. She was elected mayor of Mexico City in July 2018.

Claudia Sheinbaumna’s victory in the presidential election was generally predictable. From the first days, opinion polls showed her dominance over her main challenger and peer, Xochitl Gálvez, running for the opposition center-right coalition Fuerza y Corazón por México (Strength and Heart for Mexico). Galvez has positioned herself as a “grassroots” candidate, serving as a harsh critic of the incumbent and sometimes using atypical campaigning methods. For example, in March, at a campaign rally in the city of Irapuato (Guanajuato state), she swore on blood to lower the retirement age to 60.

At the end of the presidential election, Claudia Sheinbaum won with 58.3% of the vote and surpassed the result of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who received 54.7% in 2018 . The candidate of the opposition alliance “Strength and Heart for Mexico”, Senator Socitl Galvez, who earned about 30% of the vote, conceded defeat and congratulated Ms. Sheinbaum on her success.

In the footsteps of Lopez Obrador?

Claudia Sheinbaum and the incumbent president of Mexico share many similarities, including campaigning together and similar views. Both are modern leftists who speak of the need to reform the current economic and political system, redistribute to the needy and raise taxes on the rich. And while she insists she will govern independently of Obrador, Sheinbaum is more likely to continue his policies. Why “more likely?” – Because Latin American history shows that even the most loyal supporters, once in power, often turn their backs on their political predecessors. Such was the case in Colombia with Jaún Manuel Santos, who turned his back on Álvaro Uribe. In Ecuador, it was with Lenin Moreno, who abruptly changed the government’s course, surprising the previous president, Rafael Correa.

Meanwhile, experts believe that Claudia Steinbaum will have a harder time than her predecessor, despite her impressive election result. First of all, the new president cannot boast the same unconditional support of the people that Obrador enjoyed. Secondly, it is enough to look at the state of the economy, the social sphere and the crime situation to realize “the scale of the catastrophe”.

In 2024, Mexico will face the largest budget deficit in 24 years. The fiscal gap is approaching 6% of GDP, and by the end of the year the country’s debt will be almost 50%, and this in an economy where 17% of GDP comes from collecting taxes from citizens. In addition to fiscal problems, there are socio-economic problems peculiar to Latin American countries. As of 2022, the country’s poverty rate stood at 36.3%. But not only the economy became part of the candidates’ election program. Worst of all is security. During Obrador Lopez’s 6-year term alone, the country recorded 200,000 murders – double the number recorded during President Felipe Calderon’s previous administration (2006-2012). Mexico spends less than 1% of GDP on public security, but the world associates the country with drug cartels and street gangs. Obrador’s policy of addressing the social causes of crime has not worked; instead, the cartels have waited for elections to redistribute territory.

Political monopolism: a boon or a tragedy

As we have already noted, on June 2, Mexico held not only presidential elections, but also elections to Congress, the Senate, governors and the mayor of Mexico City. According to their results, the pro-government “National Revival Movement” (“Morena”), together with its partners in the government coalition “Let’s Keep Making History”, secured a qualified majority in the Chamber of Deputies and an absolute majority in the Chamber of Senators. Of the 500 deputies in Congress, Morena and its coalition satellites won 365 seats. The qualified majority, as Interior Minister Luis Maria Alcalde Luhan said at the summing up, allows Morena to carry out constitutional changes. In the Senate, the failed coalition won 82 out of 128 seats. At a briefing on the results of the past general elections, the minister also showed the final map of the distribution of gubernatorial positions after Sunday’s regional elections in eight states and Mexico City. In the end, Morena and her partners retain 23 of the 31 states and Mexico City, the right-wing controls 6 states, and the Citizens’ Movement has 2 states.

Mexico is now a democracy with a peaceful transfer of power between parties and generally successful elections. But this is a fairly recent phenomenon. For most of the 20th century, the country was ruled by a single political party, the PRI, in a unique form of autocracy, for which it was nicknamed “the perfect dictatorship” by Peruvian Nobel Prize-winning writer Mario Vargas Llosa.

Morena’s resounding victory, and the concentration of power in the hands of one political force, brought back unpleasant memories for Mexicans more than two decades ago. In the election, many Mexican citizens frankly admitted that while they voted for Claudia Sheinbaum, they also tried to support opposition candidates for other offices. In the United States, the election results of the ruling Morena party were seen as a potentially dangerous trend toward monopolizing political life. As Politico notes, this trend began with Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey and his neo-Islamist Justice and Development Party in 2000. Viktor Orban in Hungary and his right-wing populism gained popularity in 2010, and Narendra Modi in India and his Hindu nationalism in 2014. The common thread is a charismatic leader, a well-run party machine and the inevitable weakening of democratic institutions.

And now, 24 years after the one-party federal state led by the “Institutional Revolutionary Party of Mexico” lost the presidential palace for the first time, a new movement resembling the “PRI” but under a different name – “Morena” – has emerged in Mexico. It is worth noting that the markets did not like the one-party rule of “Morena” at all: both the peso and stocks fell sharply. Monopoly is a bad story for everyone but the monopolist, both in politics and business.

Of course, Claudia Sheinbaum and “Morena” have “ironclad” arguments: a qualified majority in both chambers will make it possible to carry out the reforms so necessary for the country and make the necessary changes to the Constitution. In this sense, the heiress of López Obrador has a good “political appetite.” Sheinbaum plans changes to the Supreme Court and the pension system. She has also promised to continue investing in major infrastructure projects in historically poor regions of Mexico. The main task of the new president will be to fight mass crime, which, despite all the efforts of the outgoing head of state, remains a real curse of the country.

Among other things, Claudia Sheinbaum intends to create a new system of criminal investigations to somehow correct the dismal statistics, according to which more than 98% of crimes in Mexico remain either unsolved or unpunished. For example, the winner of the election is going to expand the list of crimes for which suspects can be sent to jail indefinitely before trial. In addition, the population has questions about the ruling party “Morena” because the army and the National Guard are too active in the fight against crime, while the police are given a secondary role. Given that Ms. Steinbaum intends to toughen the fight against crime, she will probably have to brace herself for criticism. Mexicans do not like “militarization,” but they cannot ignore progress either. Another thing is that it can hardly be considered sufficient.

As far as foreign policy is concerned, a fundamental issue for Mexico City is relations with the United States, which today leave much to be desired. More than 2,000,000 people have crossed the Mexican border between 2020 and 2024. The country is between two fires – the US and other Latin American countries. The U.S. is demanding Mexico increase border control, internal reforms to curb illegal migration. Meanwhile, from countries like El Salvador, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Venezuela, there is an endless stream of migrants who pass through all of Mexico and go after the American dream. In March 2024, Obrador said that if the U.S. wants to solve this problem, it has to pay. Literally.

There is a second problem in relations with the United States – the flow of fentanyl. It is coming just through Mexico directly to the United States. In 2022, more than 100,000 people in the U.S. will die from this drug. During the Republican primaries in the U.S., there were proposals from politicians to build a wall with Mexico, use drones to destroy cartels in Mexico (like they killed Bin Laden in Pakistan), and deploy a U.S. military contingent along the border. The situation in a Democratic Biden administration is so critical that the Democratic mayor of New York City is demanding that Biden address the issue of illegal immigrants. And Biden has agreed to continue building a wall on the border with Mexico. This is and will be a key issue in U.S.-Mexico relations. Mexican politicians do not seek to limit the flow of migrants, moreover, they shift the problem of fentanyl to the U.S.: they say that the “moral character” of Americans is such. Biden promised that as the problem grows, the measures will become tougher.

During her election campaign, Sheinbaum proposed the introduction of work visas to control migration to the United States and Canada. She is sure that “northern countries need labor”, “walls will not solve the problem”. In her opinion, the U.S. should increase its investment in poor countries because “people leave out of necessity.” At the same time, Sheinbaum says that if she wins, she wants to build relations with the U.S. on an equal footing, not on the principle of subordination.

In general, Mexico’s foreign policy is unlikely to change globally after the election, and domestic policy is unlikely to change either. Although Sheinbaum will be the first woman president of Mexico and thus will make a revolution, one should not expect global reforms from her. It is not for nothing that election campaigns are often called a ride of unprecedented generosity and a fair of hopes. Voters shift the responsibility for the existing reality to politicians and parties, expecting that the new electoral cycle will bring changes. Sometimes they do; more often they do not. In systems with real democracy, elections can have a significant impact on people’s lives and change the vector of development of the country. In systems with electoral “democracy,” elections do not affect anything. But there is a third kind – Mexico. A country where elections are competitive, politicians and coalitions change from year to year, and problems are still not solved.

NEW MODIFICATION

Unlike in Mexico, where the victory of Morena and Claudia Sheinbaum may cement the trend of one-party rule, voters in India taught the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Prime Minister Narendro Modi a real lesson in democracy. For the first time since 2014, the BJP was able to win a parliamentary majority not on its own, but only in coalition with parties belonging to the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). While the BJP had promised to expand its majority in parliament, even assuming it would win up to 400 of the 543 seats, the vote came as a shock. While the party needs to secure 272 out of 543 seats to form a government, the BJP won 240 seats and the NDA 293. These results are in stark contrast to the 2014 and 2019 results, when the BJP single-handedly won 282 and 303 seats respectively and formed single-party cabinets.

The opposition managed to improve its position significantly in the current elections: the Indian National Congress, which leads the opposition alliance INDIA, which included 28 parties, increased the number of seats from 52 to 99, and the entire bloc won 234 seats. Either way, the election results allowed Modi, who has ruled the country for a decade, to lead the government for the third time. Modi’s victory was only the second time an Indian leader has retained power for a third term after Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first prime minister. However, the BJP’s freedom of maneuver will now be restricted by a stronger opposition and coalition allies, key among them the regional Janata Dal (United) parties from Bihar state and the Telugu Desam Party from Andhra Pradesh. So, for the leader of the “world’s largest democracy”, the new term of his government will clearly not be strewn with rose petals.

A festival of “democracy”

As festivals in India, the Indian “festival of democracy” lasted long: this year’s elections lasted 44 days – from April 19 to June 1. It was the second longest election in history – the first parliamentary elections of independent India in 1951-1952 lasted more than four months. Such a long electoral process is due to the complexity of its organization because of the enormous population. This year, a world record was set: 642 million voters took part in the elections. The turnout was 62 percent.

Voting took place in seven phases – seven days, with certain states and union territories voting in each phase, and some voting in multiple phases. Active campaigning continued throughout the election (except for the 48 hours of silence before polling days). Counting of all votes was done in one day on June 4. The completion of India’s largest election campaign in world history has shown that Indians remain undeterred by the institution of elections and believe in the democratic process as a way to improve their daily lives. Another important feature of the campaign, unlike in Mexico, was that it was completely free of violence. There was fierce polemics, there was an irreconcilable struggle between alternative strategies of different political forces, but no blood was shed.

“Modi’s Guarantee.”

The success of the BJP in the last decade is inseparable from the charismatic figure of its leader. The image cultivated by Modi and his associates of a wise, ascetic “father of the nation” is extremely popular among different sections of the population. The prime minister’s approval rating is around 75 percent. In effect, Modi turned the parliamentary elections into a campaign more akin to a presidential campaign where the BJP relied on the leader’s brand. In his 10 years in power, Modi has changed India’s political landscape, making Hindu nationalism, once a fringe ideology in India, mainstream while leaving the country deeply divided. His supporters see him as a strong leader who has succeeded on his own, improving India’s standing in the world. His critics and opponents say his Hindu-centered policies have created intolerance, while his economy, has become one of the fastest growing in the world. The GDP growth rate for the fiscal year 2023-2024 is 8.2 percent. Over the decade, the government has implemented a range of structural reforms, including in the social sector, implemented large-scale infrastructure projects, and strengthened the position of national industry and business. Many of these projects emphasize the personal role of the Prime Minister.Under Modi, New Delhi’s international position has been strengthened. In 2023, India became the world’s fourth lunar power by successfully landing the Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft on the Moon’s south pole.

However, it is also true that with economic growth has come increased inequality: the 1-2% of the richest people are doing much better than the vast majority of the population. In some ways, it is this gap that has helped large corporations, business owners in the stock market, thrive. The growth of the economy has occurred without providing jobs. With a growing population in today’s India, unemployment has become a real problem. So have increased prices.

The values of Hindu nationalism promoted by the Prime Minister resonate with many Indians. To understand the reasons for this we must know that the political party to which he belongs is a right-wing Hindu nationalist party rooted in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS, a paramilitary nationalist Indian organization with six million members). It is the equivalent of the Communist Party in terms of its influence on society. The ideology of this organization is that India is a country for Hindus and Muslims along with Christians should not have the same rights.

Modi went to RSS trainings from the age of eight and later became a member and worked there for 10 years. He was then transferred from the RSS to the BJP where he became a politician. He encouraged anti-Muslim rhetoric, under him the threat of Islam and Islamic terrorism was constantly invoked. And this has been key to his decisions in power. He took away special status from Kashmir (a disputed region in northern India with Pakistan, where the religious majority is Muslim) and sent troops there. Media freedom and the ability of Kashmiris to express their opinions are severely restricted. Modi has used the crackdown on Muslims for political purposes, showing the rest of the country what fate may await them if they disobey. Some of his most controversial speeches in this election have focused on how opposition parties favor Muslims. And Modi has inculcated hatred of Muslims, even though they make up 15% of India’s population.

His management style can be safely called authoritarian. He has built a centralized system around him, where all decisions must go through him. Modi is intolerant of dissent and dissidents in the media. Despite his position as prime minister, he does not give interviews and is afraid of confronting journalists because he might lose his temper People who criticized him have been sidelined. Political opponents in his own party – weakened. Modi does not hesitate to use security services and financial tools to fight his opponents. Modi deliberately demonstrates his religiosity: he prays, fasts, participates in religious ceremonies and calls himself a “messenger of God”. At the height of the election, he said, “Some may call me crazy, but I am convinced that Paramatma (God, the Supersoul in Hinduism) has sent me for a specific purpose”. Significantly, when Modi went to Swami Vivekananda’s island for a two-day meditation after the election campaign ended, the opposition accused him of breaking the “silence” before the last day of polling, thus recognizing the prime minister’s religiosity as a factor in the electoral battle.

The BJP’s election program was built around the slogan “Modi Guarantee”, which means that the party fulfills all of its commitments. The BJP’s rhetoric emphasized economic growth, success in poverty eradication, infrastructure projects implemented by the government, structural reforms and social programs, promising to build on its achievements.

I.N.D.I.A.

The BJP’s main rival for over two decades has been the Indian National Congress. In the run-up to the general elections, the Congress-led opposition merged in July 2023 into a new coalition, the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance, or I.N.D.I.A. for short, comprising more than 20 parties. By rebranding itself, the opposition hoped to attract votes by eloquently hinting at who really represented the country’s interests. The I.N.D.I.A. bloc presented itself as the guardians of Indian democracy, fighting the authoritarian tendencies of the incumbent government and its nationalist rhetoric. A grand coalition is nothing new for India.

The tradition of Indian politics has always been that the ruling party fights against a large national party with the support of many regional parties: the BJP too came to power in 2014 as part of a grand alliance. Because India is a huge and diverse country, there are many regional parties that often come into opposition. Modi uses this to show how weak his opponents are, but in reality the BJP has acted in the same way. Modi’s nationalist rhetoric makes it easier to win in Hindi-speaking areas. The BJP fares worst in the south, where Hindu nationalism is not as strong. Thus, local parties are proving to be much more seriously resisted than anyone would have guessed even three months ago.

Many experts noted that the BJP’s most significant losses were in poor rural areas, where farmers, lower caste communities and Dalits (one of India’s marginalized groups, formerly known as untouchables) turned their backs on Modi. The BJP was particularly hurt by its failure in the most populous state, which together yields 80 seats, Uttar Pradesh, where the ruling party lost 29 seats.

The BJP had high hopes for the opening of a temple in the city of Ayodhya at the place where Hindus believe the god Rama was born. The temple was built on the ruins of a mosque destroyed two decades ago. Modi’s visit to inaugurate the temple was the crowning achievement of his Hindu nationalist agenda and ticket to a third term in office. But religious polarization and pride in the Ram Temple ultimately did not trump anger over rampant unemployment, stagnant wages and intolerable inflation. Another state where the opposition managed to give Narendra Modi’s party a fight was Maharashtra, home to India’s business capital, Mumbai, with the country’s oldest stock exchange, the Bombay Stock Exchange. The confirmation of the fact that the election results were a surprise for everyone was the dynamics of the stock market, which was thrown from hot to cold. On the eve of the voting day, the Indian market demonstrated record growth on the wave of expectations of a convincing victory of Narendra Modi’s party. However, when real-time data on the results of vote counting in the states and union territories, which were not so rosy for the ruling alliance, began to arrive, the indices of India’s stock exchanges collapsed by more than 6%.

Moreover, the party’s position has also deteriorated in Haryana, Rajasthan, Maharashtra and West Bengal. Moreover, the share of votes cast for the BJP in rural areas has also declined compared to the 2019 elections. Resistance in the regions from local parties was an important factor in the elections. That said, the BJP’s key opponent, the Indian National Congress, was weak. Part of the family of Rahul Gandhi, the central figure and leader of the INC, heads the Congress, and this heredity is corroding the party from within. The party is poorly represented “on the ground” and the surname “Gandhi” alone is no longer enough to win. Though attempts have been made by the party to rebuild itself. One of the “chips” of the INC in the elections was the so-called Bharat Jodo Yatra, a mass procession during which leading politicians of the largest opposition party led by Rahul Gandhi marched across India, accompanied by thousands of people, where they directly interacted with voters and people of different backgrounds from all corners. This kind of “direct democracy” diversified the election campaign and contributed to a decent result for the opposition.

In semantic terms, the opposition focused on criticizing the ruling party, accusing it of undermining the secular structure of the state, authoritarianism, infringing on the rights of national minorities, high unemployment in the country, and merging with big capital. The INDIA alliance’s election promises included a nationwide socio-economic and caste survey, increased quotas for Scheduled Castes, Tribes and other backward classes, return of statehood to Jammu and Kashmir, guarantees of minimum support prices for the purchase of agricultural products from farmers, abolition of the controversial reform of recruitment in the country’s Armed Forces (when only a quarter of those who have served on a short-term four-year contract are selected for a long-term contract). In short, the bloc tried to ensure the support of the poorest strata of the population, i.e. the electorate of Narendra Modi, who traditionally acts as a leader of the common people, a man from the grassroots, the poorest castes. On the whole, the opposition I.N.D.I.A. alliance managed to refute the forecasts that promised it another humiliation.

Third term

When it was a crucial day of voting in Europe for the European Parliament elections, in India Narendra Modi was sworn in as Prime Minister, ushering in a new, coalition era of his rule. However, to become Prime Minister for the third time Modi suddenly becomes indebted to his coalition partners – a number of regional parties with very different ideologies. Earlier, the BJP’s alliance partners had played minor roles. Now, following the political logic, the situation has to change and the government will have to listen to the voice of its colleagues. Thus, the Janata Dal party from Bihar will quite reasonably demand from Modi, in exchange for its 12 seats in the coalition, to focus on the development of India’s poorest state. And Narendra Modi will be forced to negotiate compromises, something he has not done so far. And that outcome could be a win-win for the country.

Greater regional development, tackling unemployment, more equitable distribution and attention to poorer regions are the right policies that will appeal to voters. So the main focus today is on how Modi will govern after decades of political leadership where he has never had to engage in consensus politics. After the election, by the way, Modi talked a lot about consensus and that the Cabinet should be “of the people, not Modi”. However, all expectations of consensus “crumbled” after the first appointments to the government. Modi and the BJP refused to cede any important seats to coalition colleagues. All of them are still held by the prime minister’s closest associates, including Amit Shah as home minister, while the coalition parties got the ministries of heavy industries and food processing.

For the first time in India’s history, not only in Modi’s Cabinet, but also at the state level, there will be no Muslims. Therefore, Modi’s first personnel moves indicate that he is unlikely to change his authoritarian approach to governing the country, and instead of a coalition consensus, India may get increased repressive measures against dissenters. Although it is possible that, like any autocrat, Modi does not realize that this election has changed India. And ruling as before won’t work. The BJP’s Hindu-oriented cultural and social program may necessarily clash with the stance of its coalition partners and the opposition, which campaigned on the slogan of preserving India’s secular constitution. The leader of the Telugu Desam Party, one of the BJP’s alliance partners, has already said that decisions on the most contentious issues “will not be taken unilaterally”. These include the BJP’s desire to introduce a uniform civil code, instead of the various cultural customs and laws followed by different religious groups across India.

There are fears that legal uniformity will be used as a tool to marginalize minorities. Another resistance from the opposition and coalition partners may be the National Register of Citizens bill, where people will have to prove their citizenship through documents. Opponents of the draft say it is designed to portray Indian Muslims as illegal migrants. Another Modi project that is certain to face resistance from regional parties in his alliance is One Nation, One Election. Its essence is that all elections in the 28 states should be held simultaneously, rather than staggered as they are now. Many saw this as another attempt by the BJP to impose uniformity on the various states of India. Therefore, it remains unknown how the coalition arrangement will affect Modi’s ability to implement his third term government program.

However, Modi has another trump card up his sleeve – the support of the US, which is literally “strangling” him in its embrace. Why? The answer is simple. India acts as a counterweight to China in the region. In the face of China’s demographic crisis and economic slowdown, India continues to grow relative to its northern neighbor. But despite all the accolades Washington is bestowing on Modi – he is the first Indian leader to address Congress twice – there are concerns that having gained economic and political weight, India may have its own ambitions to become a great power. And that could pose a bigger challenge to the US than China. Washington is almost certain that the lesson Modi learned in the elections will serve him well and encourage him to make reforms that will make India more stable and democratic. Otherwise, the alternative of increasing Modi’s authoritarianism and nationalism is guaranteed to bring India into a different camp, ideologically different from the United States.

South Africa: Ramaphosa’s deep disappointment

On May 29, the Republic of South Africa held its seventh parliamentary elections in modern history. The National Assembly is the country’s main legislative body. The first half of the 400 deputies of the National Assembly is elected by party lists, the second half – by electoral districts coinciding with the nine provinces of the country. The “provincial quota” allows not only party members but also independent candidates to enter the parliament. There are no separate presidential elections in the country: the parliament votes for the president, so the current head of South Africa Cyril Ramaphosa needed an unconditional victory of his party, the African National Congress, to stay for a second term. However, Ramaphosa was deeply disappointed. The outcome of the elections in South Africa, as in India, broke the long thread of one-party rule. The African National Congress (ANC), ruling since 1994, received 40.2% of the vote and lost its absolute majority in parliament for the first time in its 30 years in power. True, experts say, the ANC was decades too late with its electoral defeat and will now have to stop living off the former glory of the anti-apartheid struggle and recognize its failures in real time.

Compared to the results of the last vote in 2019, the party lost 17 percentage points of support at once – three times more than it lost on average during the 2009-2019 campaigns. Many experts cite accumulated problems in the economy and social sphere as the reason for the loss of voters’ trust. These include a high – 33% – level of unemployment, property inequality, crime and corruption, degradation of the energy system, social and public services. A democratic polity, freedom of movement and expression are the few things South Africans inherited from their first black leader, the legendary Nelson Mandela, the former ANC leader who ended apartheid and resigned after his first and only term as president.

It is well known that the ANC has a fairly stable electorate that would rather not show up at the ballot box at all than vote for another party, unless of course it is a party that has split from the ANC itself. Turnout in 2024 has indeed fallen to 59% compared to 66% in 2019, but voter absenteeism alone cannot explain such electoral failure. The main threats to the ANC continued to come from within the ANC itself: it is intra-party splits that provoke the greatest voter exodus.

Not surprisingly, a decisive blow to the ruling party’s position was dealt by the 82-year-old former South African president Jacob Zuma, who was sentenced to 15 months in prison in 2021 for failing to appear in court for a corruption trial during his years in power. In South Africa, he is also called the Rasputin of South African politics. In late 2023, he formed his own party, Umkonto ve Sizwe (translated in Zulu: “Spear of the Nation”; this was the name given to the militant wing of the ANC during the anti-apartheid period). The new party’s ratings began to rise rapidly. Zuma’s ideology and the key theses of his program have long been known and are not new: the fight against the “evil influence of the West”, in particular the United States, the fight against same-sex marriage, redistribution of assets, socialism for society and overconsumption for himself and his closest supporters, reliance on the Zulus – the largest ethnic group in the east of the country. As the politician remains popular among certain groups of voters, especially in his home province of KwaZulu-Natal, even the fact that on May 20 the Constitutional Court barred Jacob Zuma from standing for election because of an outstanding criminal record did not help to cool the fervor of his supporters. His party eventually won the KwaZulu-Natal election by a landslide (45.9% to the ANC’s 17.6%) and came third in the national vote with 14.6% support. This result came as a complete surprise to the ANC.

Fourth place with about 10% of voter support went to the ultra-leftist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party, led by 43-year-old Julius Malema. He has traditionally spoken with Bolshevik bluntness about solutions to key problems, suggesting simply building new power plants to get rid of power outages, and nationalizing businesses and banning layoffs to solve unemployment problems. Previously, he had repeatedly advocated confiscating land from white South Africans. However, the former leader of the ANC’s youth wing, twice convicted of hate speech, can only implement his program by joining forces with his former boss and current opponent Jacob Zuma, as well as with the current president.

John Steenhuisen, leader of the Democratic Alliance (DA) party, has vowed to his constituents not to allow a possible alliance between the ANC and its “youth league in exile” – the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party, as well as Zuma’s Umkonto ve Sizwe party, which the media have already dubbed a “doomsday coalition”. Such a coalition at the head of the country, according to the DA leadership, paves a direct path for South Africa to become a “second Zimbabwe” – a country that has effectively expelled whites and destroyed its own economy. “Today, our country suffers the unbearable burden of unemployment, crime and poverty. But these disasters were not inevitable. They were deliberately created by people. If we sit back and allow a coalition to be built between the ANC, EFF and MK, our tomorrow will be much, much worse than yesterday. Property will be expropriated without compensation, corruption will engulf us and the economy will collapse,” Steenhuisen warned during the election campaign. Therefore, despite significant contradictions with the ANC in the Democratic Alliance, the possibility of becoming a junior partner of the ANC was not ruled out. Such a coalition could potentially attract the Inkatha Freedom Party, a right-wing conservative party of the Zulu aristocracy, which has a pre-coalition agreement with the DA and has been moving closer to the ANC in recent years.

In the election results, the right-liberal Democratic Alliance (DA), finished second with 21.8% of the vote. For many years, the DA has been the official opposition in parliament. A party representing the interests of the white minority and big private business. “Democratic Alliance” is a classical liberal party, advocating the rule of law and market economy and showing good practical results. For example, the Western Cape, where the Alliance won the majority of leadership positions in the last election, is one of the richest and most developed provinces in the country. Anticipating future coalition bargaining, party leader John Steenhuisen said South Africa is now moving towards a “coalition country”.

An era of new hope

Believing that the ANC would rule forever, the election results shocked the leadership of the African National Congress. Never before has the ANC had to engage in shared governance. South Africa’s constitution states that the new parliament must convene and vote for a president within 14 days of the election results being announced.

Coalition governments are an unusual thing for South Africa; politicians simply lack experience in compromise and reaching sustainable agreements, and the legislation that would regulate the activities of such governments has simply not been developed yet. Therefore, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa recalled the historical past. He proposed a government of national unity, citing the 1994-1996 period when the ANC, the former liberation movement, governed the country with partners including the National Party, which governed South Africa during apartheid, and the Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party.

Given the time deadline, intensive negotiations with potential coalition partners began. The ANC first held talks with the far-left Economist Freedom Fighters (EFF). This force was also hurt by the ascendancy of Zuma’s party, so it softened its confrontational rhetoric and dropped its main demand, the resignation of President Ramaphosa. In addition, the ANC and the BEC have a history of coalition cooperation in the Gauteng metropolitan province. Nevertheless, it is known that on the eve of the elections, the party demanded the portfolio of Finance Minister as a condition of the coalition agreement. The party has given this post to its deputy chairman, the scandalous politician Floyd Shivamba. For the ANC, this option is unacceptable: surrendering such an important portfolio to a representative of the BEC, which advocates nationalization of banks and mines, would scare away big business. In the conditions of economic stagnation and acute energy crisis, this decision looks suicidal. Therefore, to save face EFF leader Julius Malema said he would not join a government with the “neo-colonial” DA, which he called “our enemy”. An ANC alliance with Zuma’s party was another possible option for South Africa’s coalition future. For the ANC, however, it looked disastrous, as it meant, if not a de facto return to power for former president Jacob Zuma, then a guarantee of his freedom and a “pass” into government for right-wing populist elements. Zuma’s party, however, made exorbitant demands for participation in a coalition with the ANC, namely Mr. Ramaphosa’s resignation.

The third option was a coalition with the Democratic Alliance (DA). For many politicians in the ANC’s national and regional bodies, this option was also unacceptable. Cooperation with the DA, which, in their opinion, represents the interests of “white monopoly capital”, looks like a betrayal of the ideals of the struggle against apartheid, for the interests of the black majority. The ANC is particularly at risk in the Eastern Cape, where the party’s position is traditionally strong (this year the party won 62.5% of the vote in this province – the second result after Limpopo with 74.2%). The ANC provincial leadership in this province is strongly opposed to an alliance with the DA.

The presidency at stake, disguised as Ramaphosa’s centrist preferences eventually won over the more left-wing factions of the ANC who wanted to strike an agreement with the breakaway parties. The ANC eventually announced the formation of a majority coalition with the Democratic Alliance and two other minor parties, the Zulu nationalist Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) and the Patriotic Alliance (PA), which wants to bring back the death penalty and deport illegal migrants. The inclusion of both parties, which scored 3.8% and 2% respectively, was seen by experts as a way to channel criticism for the ANC’s collaboration with the white DA party. The markets reacted positively to the creation of such a coalition, and it was supported by big business and international investors.

Despite the unsettled coalition agreement Cyril Ramaphosa was elected president of the country for the second time at a meeting of the National Assembly of the Republic of South Africa. 283 MPs voted in favor of his candidacy, 44 were against. “I declare the Honorable Cyril Ramaphosa as the duly elected president,” South Africa’s Chief Justice Raymond Zondo said at the sitting of the new National Assembly.

Ramofosa now faces the question of appointing a government. The coalition agreement requires the parties’ share of parliamentary members to be taken into account. The coalition currently has six members and 273 seats, with the coalition holding 159 seats and the DA 87.As The Guardian notes, negotiations on government positions will soon be finalized, a Ramaphosa spokesman told national broadcaster SABC. “The president does not want the country to go through a long period of uncertainty,” he said. And now a new, and in some places old, but now coalition government will be sorting out the “legacy” of the ANC’s one-party rule, which presents a long list of problems, from the need to create jobs to tackling violent crime and ensuring that power cuts, which have lasted up to 12 hours a day in recent years, do not resume.

In general, analysts are not particularly optimistic about the coalition future of South Africa in the current electoral cycle (2024-2029). Since 2016, all coalition governments in large municipalities (Tswane, Johannesburg, Nelson-Mandela Bay) have failed. One of the reasons is incompatibility of ideological positions.

Nevertheless, it is hoped that the end of the ANC’s one-party rule and the advent of an era of coalition politics in South Africa, despite a period of difficult compromises in policy and personnel decisions, will have more positive consequences for business and citizens. A coalition government will give the parties the opportunity to shape the previously absent system of checks and balances, and will also allow for the breathing of “fresh personnel blood” into the government that will infuse it with new ideas to develop effective policies on all key issues. And it is hard to imagine that what lies ahead for South Africa will be worse than the reasons for this political reset.