In March of this year, the European Council, following the EU summit, decided to begin negotiations on the accession of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BH) to the EU. This was announced by the President of the European Council, Charles Michel.

He named the decision a “key step forward” on BH’s path to the EU. According to him, work needs to continue so that “Bosnia and Herzegovina develops steadily, as its people want.” “Your place is in our European family,” Michel wrote on his X account.

Bosnia and Herzegovina received its candidate status from the EU in December 2022. Then, this surprised many. After all, one of the first associations that arise among European politicians and officials in connection with the mention of Bosnia and Herzegovina is a mix of endless conflicts – a failed state. According to European leaders, their decision should help accelerate governance reforms in the country so that Bosnia can finally break out of the endless cycle of government crises. But there was another reason: by “advancing” the rapprochement of Sarajevo with Europe, the leaders of Western countries also sought to block the actions of the Kremlin, which in recent years has been trying to destabilise the situation in the country, using the complex ethnic and political structure of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In this paper, Ascolta analyses the current political situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina and also examines integration trends in the Balkans, which are increasingly facing geopolitical challenges and threats.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

In December 2022, the European Union decided to begin accession negotiations only with Ukraine and Moldova. Bosnia only expressed its readiness for this “as soon as the necessary degree of compliance with the membership criteria is achieved.” Now, in Brussels, it seems they considered that this degree has been “reached”, and BiH can be connected to Ukraine and Moldova on their way to the European Union. The “forced” European integration of Bosnia and Herzegovina is taking place against the backdrop of a deep crisis and confrontation within the country.

On the eve of the EU decision to begin negotiations with Bosnia and Herzegovina, a report by the US National Intelligence Service on threats in the world was published. The Balkans have a relatively small place in it, but the authors predict that the region in 2024 “will likely face an increased risk of localised inter-ethnic violence.” At the same time, only one name is mentioned in the Balkan section – the name of Milorad Dodik, the President of the Republika Srpska (RS), which is part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. “He is taking provocative steps to neutralise international control in Bosnia and Herzegovina and ensure the de facto secession of Republika Srpska,” the document’s authors warn.

In this regard, the coincidence of the announcement of the EU decision to launch negotiations with Bosnia and the publication of the report of the US National Intelligence Service with the mention of only one name in the Balkan section – Milorad Dodik – may not be a coincidence. In any case, the signal to the Bosnia and Herzegovina authorities about what or who could prevent the republic’s further movement towards Europe turned out to be unambiguous.

It is worth noting that Milorad Dodik himself, not without reason, gives reasons to consider him the main threat to the integrity of BH and a barrier to the country’s European future. Thus, during a recent meeting with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Dodik threatened to declare the independence of the Republika Srpska if Sarajevo resorted to alienation of property. At the end of last year, he stated that if Donald Trump wins the US presidential election in November this year, he again intends to consider the issue of independence and the withdrawal of the Republika Srpska from BH.

However, it would be a simplification to reduce everything to the simple formula “Dodik against everyone.” Bosnia and Herzegovina is a tangle of ethnic and religious contradictions, where Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs have a lot of claims against each other caused by the historical past, the bloody war, as well as the cultural characteristics of each ethnic group. Nationalism has become, perhaps, the main problem of the country on the path to real progress since each of the ethnic groups puts its interests above the interests of a single state. Therefore, the road to the EU for BH does not promise to be strewn with rose petals. Regardless, Bosnia and Herzegovina is no stranger to this, and the historical experience of the people inhabiting BH is further confirmation of this.

Religion and history

Religion is the primary “ethnic marker” that divides groups on the Balkan Peninsula.

The Serbian population represents the Orthodox tradition, the Croats adhere to Catholicism, and the Bosniaks are Muslims. Although belonging to one of the faiths does not always mean the religiosity of each member of the group, it formed a different cultural heritage, and as a result, three separate nations united under the dome of one state—Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Originally, Islam was embraced, having consciously entered into an alliance with the Ottomans, by that part of the indigenous aristocracy of medieval Bosnia, whose ancestors, Bogumil Christians, opposed both the Catholic and Orthodox churches. Although linguistically and ethnically, they are almost identical groups, their choice of religion divided their followers into three different communities. Catholics were called “Latins”, Orthodox “Greeks”, and Muslims “Turks”, although they were all Yugoslav, linguistically and genetically.

When empires began to disintegrate, the ethnicisation of these communities began. Catholics, whose roots were in the Kingdom of Croatia, began to consolidate as Croats, and Orthodox, whose roots went back to the medieval “great župa” of Raška, began to consolidate around the Serbian Orthodox Church as Serbs. Muslims found themselves in a worse position at this moment. In the newly independent Serbia, as well as in many other countries that derived from the Ottoman Empire, they were subjected to outright genocide.

However, Croatia and Bosnia, in which the Slavic Muslims historically had the strongest positions, found themselves part of the Austrian Empire after the departure of the Ottoman Empire in 1878. At the same time, in Bosnia, along with local Muslims, there were also Catholics and Orthodox Christians who began to recognise themselves as Croats and Serbs, respectively. But if the Serbian view of Muslims was completely hostile, then the ideologists of the emerging Croatian nationalism tried to win local Muslims over to their side. Yet, Muslims themselves, for a long time, avoided national identification and identified themselves along religious and territorial lines. The latter manifested itself later in the royal First Yugoslavia that emerged after the First World War, whose authorities in 1939 decided to divide the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina between the Serbian and Croatian Banovinas, which caused a sharp protest from local Muslims. A few years later, when Yugoslavia collapsed under the blows of German tanks, Muslims found themselves between the hammer of Serbian and the anvil of Croatian nationalism.

In the second socialist Yugoslavia, formed after World War II, Bosnia and Herzegovina became a separate republic. But in terms of nationality, Muslims, for a long time, had to choose either Serbian or Croatian (or other theoretically recognised) nationalities or live as people without an exact nationality. Most of them were like this until a separate nationality, “Muslims,” was recognised in 1961. In the wake of Soviet perestroika, democratisation also affected Yugoslavia.

In 1990, Islamic revivalist Alija Izetbegovic, released after fourteen years in prison for promoting Islam, created the Democratic Action Party. Its goal was to fight for the rights of Bosnia and Herzegovina and its Muslim people. The emergence of national movements, which rapidly developed into interethnic antagonism, happened against this background throughout Yugoslavia. One can argue for a long time about the reasons for the collapse of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), which rests on a fragile interethnic balance. Still, one cannot fail to note the role of the Chairman of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Union of Communists of Serbia, Slobodan Milosevic, in this. He had his views on how to prevent the collapse of Yugoslavia. However, he acted in the spirit of “we wanted the best, it turned out as always.”

Milosevic decided to play the Serbian card to seize power in Serbia and, through it, throughout Yugoslavia. It was he who, instead of trying to reconcile the parties and search for a compromise in the autonomous province of Kosovo, where Albanian-Serbian contradictions were growing, unequivocally supported the local Serbian minority, abolished Albanian autonomy and introduced Serbian troops and direct Serbian rule there. In response to this, realising that Milosevic had begun the Serbization of multinational Yugoslavia, Slovenia announced its separation. And when Yugoslav troops were sent to it (from Serbia they could only pass through Croatia), the latter also rushed to leave Yugoslavia. In response, Milosevic supported the creation of the Republic of Serbian Krajina in the territories of Croatia with compact residence of Serbs, as well as the consolidation of Serbs in other republics where their positions were strong.

Thereon, the situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina was extremely difficult since its population consisted of 43% Muslims, 31% Serbs and 18% Croats. At the same time, Muslims had to deal with both Serbian parties, which demanded the preservation of Bosnia as part of Yugoslavia, and Croatian parties, which advocated leaving it after Croatia. In such a situation, Alija Izetbegovic, for some time, tried to fight for the interests of Bosnia and its Muslims within Yugoslavia, the preservation of which he advocated in the form of a renewed democratic confederation. The same course was pursued by the reformist government of Yugoslavia, headed by the Croatian Ante Markovic – the “Yugoslav Gorbachev”, who had the support of Europe.

Regardless, the situation was changed by Milosevic’s seizure of power in Yugoslavia, which became an “explosive mixture” of Yeltsin and the State Emergency Committee. The destruction of Croatian Vukovar by the Yugoslav army at the outbreak of the war had a shock effect on those who still harboured hopes for the preservation and revival of Yugoslavia. When what was happening was discussed in the parliament of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the leader of the Bosnian Serbs, Radovan Karadzic, decided to intimidate the Bosnian Muslims with the fact that if they repeated the Croatian and Slovenian scenario, “the Muslim people could disappear,” because, in the war that would inevitably follow, they would not be able to defend themselves. Immediately, Alija Izetbegovic took the floor and stated that Bosnia and Herzegovina’s exit from Yugoslavia is irreversible because non-Serbian people have no future in such a Yugoslavia. As for the threats made, he assured Karadzic that the Muslim people would stand.

On October 12, 1991, the Bosnian parliament, with the votes of Muslims and Croats, adopted a declaration of independence for Bosnia and Herzegovina. In February 1992, a referendum was held at which the independent Republic of BH was officially proclaimed. However, the Serbs, who comprised almost a third of the population, boycotted the vote and refused to accept its outcome. They announced the creation of their independent Republika Srpska, supported by the Serbian authorities with Slobodan Milosevic. Following this, the war began. The conflict involved the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA), which at that time consisted mainly of Serbs, the Croatian army, as well as mercenaries from all sides and NATO armed forces.

The war was especially fierce because Muslim Bosnian, Serb and Croat villages were sometimes located several kilometres apart. In large cities, representatives of different communities lived next to each other. Initially, the advantage in strength and weapons was with the Serbs, who made up the majority of the soldiers and officers of the former Yugoslav People’s Army stationed in Bosnia. But quite quickly, the Muslim Bosnians and Croats restored parity of power. BH was actively helped by the Islamic world, to which Alija Izetbegovic turned, and at various times, the Croats provided active assistance to her. However, as well as vice versa – in 1995, it was the offensive of the Bosnian army in the Bihac area, which drew back Serbian forces, that helped the Croatian military carry out the successful Operation Storm, during which it liquidated the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina.

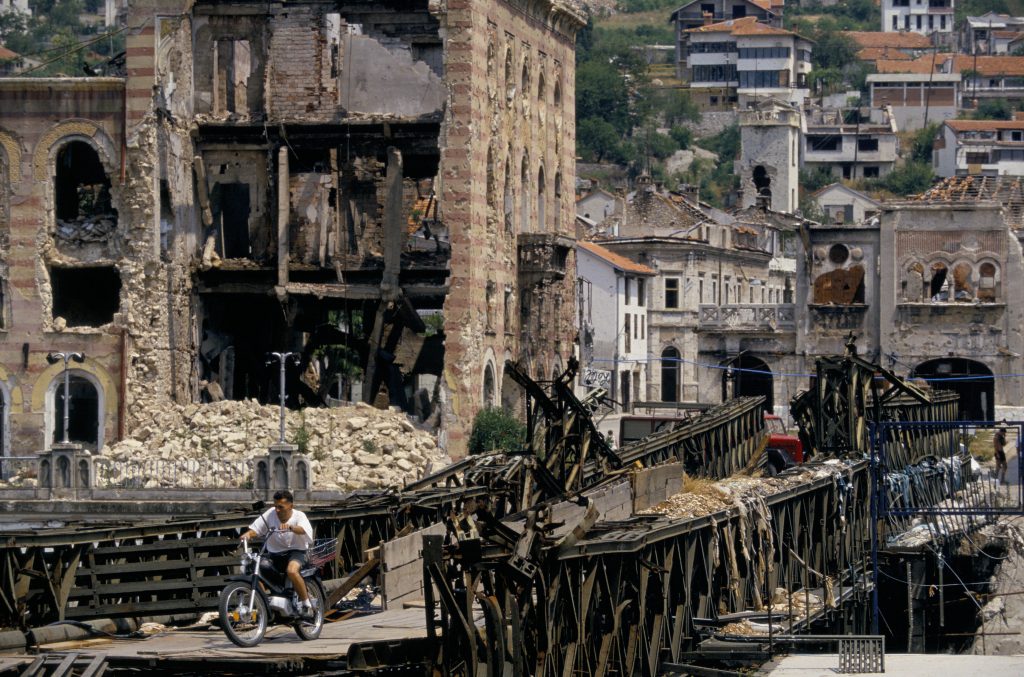

At the beginning of the war, the Serbs besieged the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo, which Bosnian Muslims defended. Artillery fire and sniper fire from the high ground around the city were almost constant. Over three years, more than nine thousand people died in the town, a third of whom were civilians (Serb losses are estimated at three thousand people, a third of them were civilians). The fighting primarily consisted of indiscriminate shelling of cities and villages, ethnic cleansing and genocide of civilians, which were carried out by all parties to the conflict without exception. UN attempts to stop the killings by creating “safe zones” guarded by peacekeepers have not always been successful. The final episode of the war was a series of artillery shell explosions in Sarajevo’s Markale market in August 1995, which killed more than 100 people. Having blamed Serbian troops for another massacre, NATO began intensively bombing Bosnian Serb positions. As a result, they agreed to negotiate.

The Bosnian War does not have a single history. There are only significantly different interpretations of the events of the 1990s, ingrained in the consciousness of the three main peoples of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BH) – Bosnian Muslims, Serbs and Croats. All three peoples were drawn into internecine fighting amid the collapse of the Yugoslav federation. All the warring parties claim that they were only defending themselves because they were threatened with extermination by the enemy.

The West, not unreasonably, puts the vast majority of responsibility for the conflict outbreak on the Serbians. The Serbs were subject to significant sanctions; it was their positions that were bombed by NATO aircraft. A special ad hoc tribunal was formed in The Hague to try war criminals of the highest rank – political leaders and generals of all warring parties. Most of those accused and convicted at this tribunal represented the Serbian side. It is no coincidence that this war is called the bloodiest in Europe after World War II and before Putin invaded Ukraine. Approximately 100 thousand people died during the war. Another 2 million became refugees (with the pre-war population of the republic being 4.4 million people). During the war, large-scale war crimes were committed that became known throughout the world, including the mass shooting of thousands of unarmed men in Srebrenica. Damage from the war amounted to tens of billions of US dollars. The economy and social sphere of Bosnia and Herzegovina were almost completely destroyed.

Eventually, although delayed, a ceasefire was reached through international intervention and two individual agreements were signed, ending the war between the parties. The first is the Washington Agreement, signed between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia on March 1, 1994. Under this agreement, the conflict between Bosnian Croats and Bosniaks ended, and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina was created, which was to be formed by the two peoples.

The second agreement was concluded at the initiative of the United States of America, on November 21, 1995, with the participation of the President of Bosnia and Herzegovina Alija Izetbegovic, the President of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Slobodan Milosevic and the former President of Croatia Franjo Tudjman. Indeed, the Dayton Peace Agreement or the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina was initialed on that date. The treaty was officially concluded at a ceremony in Paris on December 14, 1995, and therefore, the Bosnian War was considered to be completely ended.

The Dayton Accords: a life preserver or time bomb?

This year marks 29 years since the signing of the Dayton Peace Accords. They not only brought peace to Bosnia but also laid the foundation for its complex, multi-component political system. It is based on the division of the country along ethnic lines into two political entities (entities) – the Republika Srpska, which accounts for 48% of the country’s territory, and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which accounts for 51% of the territory. Republika Srpska (RS) has a more unitary structure, while the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is divided into ten regions, each with its own unique executive, judicial and legislative bodies. In addition, on 1% of the country’s territory there is the Brcko district, which is under an international mandate: it also has an autonomous government not associated with any entity, executive and judicial authorities and its own police.

This entire system is one of the most complex in the world. The central authorities in Sarajevo are formed through independent elections in each of the three ethnic parts of the state, and each leader thus elected has the right of veto. Ultimately, the heads of state are three elected representatives from three different nations who can veto each other’s decisions. They are elected for four years and alternate terms of eight months and terms.

It is not very difficult to paralyse such a complex system: it is enough for one of the leaders to constantly block the decisions of others, blackmailing them with separatism. The shortcomings of the Dayton model were already visible then. But to end the war, any price was considered acceptable. Over the years, Dayton’s flaws only became more apparent. And today, Bosnia and Herzegovina is a dysfunctional state that is close to paralysis of the central government and perhaps, God forbid, to collapse. It is saturated with fear and total distrust of ethnic groups towards each other. Bosniaks are afraid of Serbian and Croatian separatism, which will condemn them to life in a territorially small and economically unstable enclave. Serbs and Croats fear the centralisation of the state itself since Bosniaks outnumber them (according to the last census of 2013 – Bosniaks 50.12 %, Serbs 30.83%, and Croats 15.43%).

These fears explain the behaviour of a large part of the electorate in BH, which gives preference to ethnonationalist parties: the Union of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD) of Milorad Dodik in the Republika Srpska, the Croatian Democratic Commonwealth (HDZ-BH) of Dragan Covic in the Croatian part of the Bosniak-Muslim Federation and the Party of Democratic actions (SDA) of Bakir Izitbegovic of the Bosniak part of the Bosniak-Muslim Federation. In addition, today government positions in different political parts of BH are also held along ethnic lines. All these factors do not allow us to take a step forward to overcome contradictions. But the transition to a civilian matrix of political representation – when any Bosnian citizen of any nationality can occupy any government position and run for any office – would be a genuine step forward towards the peaceful “stitching” of the state and support for political reforms.

Theoretically, there are two ways to overcome the problem of the inoperability of the political system in BH. This is either centralisation or the victory of civil liberal parties in all parts of the country. In fact, the collapse of the state is not an option: the Dayton agreements do not provide for the process of secession of any part of BH; changing the Balkans borders will only lead to chaos. Any ethnic group living compactly in any state will seek independence or annexation to a neighbouring state.

Even though Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Western partners fully support the strengthening of the central government, the centralisation scenario is challenging to implement in practice because it also goes against the Dayton Agreement and would cause powerful resistance from the Bosnian Serbs, as well as the Bosnian Croats. Russia, by contrast, advocates greater autonomy and powers for the confederate units, fueling Bosnian Serb separatism for years. As we have already noted, the only feasible scenario for overcoming BH’s contradictions is the electorate’s transition from the ethno-nationalist paradigm to the civic-liberal one. The process has begun: Bosniak and Croat representatives are the leaders of moderate civil parties, but the Serbian part of BH continues to be dominated by Milorad Dodik.

Another “legacy” of Dayton was the institution of the High Representative. This international official plays the role of political oversight of the situation in the country and is elected not by the citizens of Bosnia but by other states that are part of the Council for the Implementation of the Dayton Peace Agreement. Russia is also among the members of the Council, but Western countries have a majority in it. Last year, Russia tried, through the UN Security Council, to block the election of a new High Representative, Christian Schmidt, taking advantage of the fact that it is the Security Council that must confirm with its resolution the decisions of the Council on the implementation of the Dayton Agreement.

The High Representative has fairly broad powers. For example, he can remove from office any person in the political system of Bosnia and Herzegovina, prohibit anyone from participating in elections at all levels, and also make decisions, albeit temporary, but binding on all authorities of the country. He has the power to change the structure of the political system itself. However, Christian Schmidt is not ready to break the entire state system but demonstrates a willingness to make targeted changes, especially in the electoral sphere, in order to ensure the functionality of the most important state institutions. After all, the reason for the existence of the institution of the High Representative in Bosnia is to prevent the country from experiencing a total paralysis of power, which would return the state to the path of civil war, the possibility of which still remains.

The need for significant changes is recognised by many, but the problem is that the Dayton model provides virtually no opportunities for legal adjustment. Therefore, the leader of the Republika Srpska (RS), Milorad Dodik, who constantly threatens to secede from Bosnia, presents himself as a “defender of the true Dayton,” and the day of signing the Dayton agreements is a public holiday and a day off in the RS. Today, it becomes clear that the Dayton model, which was thrown to Bosnia and Herzegovina 29 years ago as a life preserver, turned out to be something of a time bomb. And it is no longer only threatening Bosnia.

Confusing elections

The complexity of the political system of Bosnia and Herzegovina, generated by the Dayton Accords, is manifested not only in the functioning of state institutions but also in the electoral system. On October 2, 2022, general elections were held in Bosnia and Herzegovina. These elections were the ninth since the end of the war and the signing of the Dayton Accords. The uninitiated can easily get lost in the intricacies of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s electoral system. Citizens of this country elect five presidents and four vice presidents, speakers of three parliaments and ten local parliaments, and about 500 deputies of 14 parliaments.

It is important to immediately note the background of instability in which the elections occurred. Some observers said that such a situation had not happened since 1995, when the war ended. Russia’s full-scale aggression against Ukraine coloured the external background. An atmosphere of fear and hatred permeated all key participants in the election race. This was especially true of the leaders of the three main parties of the Bosniak SDA Bakir Izetbegovic, SNSD Milorad Dodik and HDZ Dragan Covic, whose rhetoric returned the citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina to bloody war memories. Each of the leaders built a campaign on protecting their ethnic groups from the threat of Bosniaks/Serbs/Croats: “We defended once (meaning the Bosnian war) – we’ll defend again.” In addition, the elections took place against the backdrop of unprecedented outside interference.

The Turkish President openly supported Izetbegovic during his visit to Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Croatian authorities openly supported the HDZ BH. Some analysts even noted that this party received information support from the Croatian intelligence services. But Russia had the biggest influence on the course of the elections. A few days before the elections, Republika Srpska leader Milorad Dodik travelled to Moscow and met with Vladimir Putin, where he wished him success in the elections. Apparently, in gratitude for the support, in his election speeches, Dodik supported Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, changed his attitude towards European integration from positive to negative and stated that by 2030, the RS will become an “independent state.” Russian diplomats pressured and threatened BH’s European and Euro-Atlantic options. In addition, appearances by foreign politicians at campaign events and media interviews have become a common feature of the campaign. If we talk about the campaign results, we can note changes that could be the beginning of future changes.

First of all, they concern the Presidium of BH. Despite Erdogan’s support, Izetbegovic “flew” in the fight for a place in the Presidium from the Bosniak people. Bakir Izetbegovic’s dream of a unitary state without any entities, a tripartite Presidium and Serbian and Croatian flags has turned out to be a fantasy. The victory in this battle was won by Denis Becirovic, a candidate from the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and a professor of political science. He supports the course of integration into the EU and NATO and is committed to changing the ethnic principle of BH’s formation to a civilian one.

Among Croatian candidates, Zeljko Komsic took first place with 54.21% of the votes. His position is similar in view to Becirovic. Košmic’s victory was a personal defeat not only for HDZ BH leader Dragan Covic, who at the last moment abandoned the fight for a seat in the Presidency of the Croatian people in favour of his “right hand” in the party of Borjana Kristo, but also for Croatian Prime Minister Andrej Plinković. Another interesting detail: Covic and Dodik, with the support of Croatia, actively fought against Kosmic because of his position on the future of Bosnia and Herzegovina since he opposed the ethnic nature of the electoral process and the state structure of the country.

But among the Serbian candidates, there were no surprises. From the Serbs, a place in the praesidium was taken by the candidate from the Union of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD), Zeljka Cvijanovic (52.65 per cent), who, before the election, was a president of the Serbian part of the country. She is a close ally and party member of Milorad Dodik and supports him in all his endeavours. For this, by the way, in July 2023, she came under US sanctions. Milorad Dodik himself changed his seat in the Presidium of BH to the Presidency in the Republika Srpska. True, he had a hard time in the elections. Dodik almost lost his victory: opposition candidate Elena Trivich was in the lead in the number of votes on voting day, but the next morning, the results changed in Dodik’s favour.

Elena Trivich from the Party of Democratic Progress took part in the presidential elections for the first time. She is a pro-European politician, and during her election campaign, she promised to focus on the fight against corruption. Like Milorad Dodik, Jelena Trivic also declared her victory. Supporters of the opposition (Serbian Democratic Party, Party of Democratic Progress and Movement for Justice) organised large-scale protests in the administrative centre of the Republic of Srpska, Banja Luka. In the end, after a recount of the ballots, the Central Electoral Commission declared Milorad Dodik the winner of the presidential race.

In turn, Dodik accused Sarajevo and the West of trying to remove him from power illegally. He organised a counter rally in Banja Luka, where director Emir Kusturica gave a speech. However, the very fact that the venerable politician surpassed the young opposition candidate by only 27 thousand votes sounded to him like a severe warning about his political future. The defeat was painful for the RS opposition as well, and it was followed by the resignation of the leader of the Serbian Democratic Party and a split in the leadership of the Party of Democratic Progress.

It must be said that in the elections to the People’s Assembly of the RS, Dodik’s party did not have a stunning advantage. SNSD received 35% of the votes and won 29 seats (out of 83), and if not for its coalition allies, it would have lost its parliamentary majority. As a result, together with their satellites, they received the coveted majority of 53 mandates. The opposition got only 25 seats, and another 5 mandates went to the association of Bosniak parties, “Movement for the State”.

As for the elections to the House of Representatives of the national parliament, the majority there, as before, belongs to the three “old” ethno-national parties: SDA, HDZ BH and SNSD.

The picture is similar in the House of Representatives of the Federation Parliament. Formally, here too, the SDA was in the lead – 26 mandates, plus 12 for Komsic’s Democratic Front (out of 98). The CDU bloc won 15 seats. The main rival of the SDA, the Social Democratic Party of Becirovic, has the same number. Those who formed the so-called “Troika” with her – “People and Justice” and “Our Party” received 7 and 6 mandates, respectively. The rest went mainly to small Bosniak parties, which were also not very friendly to the SDA, which had been in power for too long. Therefore, the Troika quickly turned into the Eight (“Social Democratic Party”, “People and Justice”, “Our Party”, “For Bosnia and Herzegovina”, “F. Kasumovic’s Bosnian-Herzegovina Initiative”, “Democratic Action Movement”, “People’s European Union”, “For New Generations”) and set a course for forming power together with the CDU, ignoring Izetbegovic’s desperate attempts to lure someone from their number.

In turn, the CDU already had an agreement with Dodik. Therefore, after short negotiations, an agreement was reached that the CDU would create the government of the Federation with its allies and the G8. At the national level, the SNSD would also join the Cabinet. As a result, the government of Bosnia and Herzegovina was headed by the representative of the Social Democratic Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Nermin Niksic. The chairman of the Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina was an ally of HDZ leader Dragan Covic and a “loser” in the fight for a seat in the Presidium of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the Croatian people, Borjana Kristo.

The confirmation of Cristo as head of the coalition government became a fragile compromise between the HDZ, G8 and SNSD and a separate element of the agreements between Covic and Dodik. One need only look at the contents of their agreement to understand that the government’s position will remain precarious. Thus, the Croatian and Bosniak parties (and especially the SDA) have always advocated joining NATO, while the Serbian ones are against it for maintaining military neutrality and coordination with Serbia on this issue. As a result, the clause on movement towards the North Atlantic Alliance in the agreement was passed over in silence. At the same time, unanimity was reached regarding “European integration” and the speedy implementation of the 14 conditions set by Brussels. In addition, Boryana Cristo achieved satisfaction with her key demand: the long-desired reform of the electoral law. The Serbian side was also pleased.

For a long time, the implementation of critical economic projects (including with the Russian Federation’s participation) on the RS’s territory was blocked from Sarajevo, and the Serbs responded symmetrically, not allowing their implementation in the Federation. Then, the partners agreed to remove these double-edged barriers and even actively practice joint investments. Moreover, the most significant participants in the coalition, the HDZ and SNSD, had sufficient political weight to push through the necessary decisions, threatening to deprive possible opponents of the Bosniak G8 of a place in the power structures. In the Bosnian political climate, minor political parties that are left out do not last long.

Another significant point supporting the unity of the Cabinet was the need to demonstrate to Brussels its “cooperativity” – readiness for dialogue, compromise and cooperation. Under these conditions, any “troublemaker” will lose not only Western support but also funding. Actually, it was for this reason that Bakir Izetbegovich and his SDA lost their former Western patronage. It is noteworthy that even Milorad Dodik, who, even after signing the agreement, did not consider it necessary to hide his Eurosceptic sentiments, changed his rhetoric. Instead of talking about the unviability of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the possible secession of the RS, which is what he used to tease his opponents with, he began to talk about the amount that should be asked from Brussels to implement his demands.

Then it seemed that in the emerging international situation (Russia was unwinnably “bogged down” in the war with Ukraine, and Serbia could hardly withstand the growing Western pressure and the aggravation of the situation in Kosovo), the experienced politician adapted to the new political realities. Generally, the focus of attention of the newly elected government has shifted from political and symbolic issues, which are very convenient for ethnopolitical mobilisation, to socio-economic problems, where it is easier to find mutually beneficial solutions that meet the interests of the population. However, as time has shown, something went wrong.

Schmidt’s game as a trap for Dodik

We have already mentioned the role of the institution of the High Representative in the political life of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Today, there is a real fight between the President of the Republika Srpska Milorad Dodik and the High Representative Christian Schmidt. This has never happened in almost 30 post-war years. This is despite the fact that, according to the Dayton Agreements, Schmidt can find justice for any politician in Bosnia and Herzegovina. With the adoption of an additional agreement, the so-called Bonn powers, in 1997, the office of the high representative de facto gained the ability to cancel decisions at any level and make legally binding instructions. However, the mechanism for the appointment of Christian Schmidt as UN High Representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2021 has been controversial. Milorad Dodik does not recognise the legality of Schmidt’s appointment to this position, explaining that Russia did not support his candidacy for the position in the UN Security Council.

Initially, the current leader of the Republika Srpska came to power with the support of the West and a rhetoric of reconciliation, opposing himself to the previous militant leaders. However, over time, he completely switched to their positions and began positioning himself as a continuation of their course.

Christian Schmidt knew who he was dealing with and began a careful game with Dodik, understanding that sharp movements towards the Republika Srpska and its leader would cause an extremely aggressive reaction in Banja Luka, which the Kremlin would support with all available resources. Schmidt began to act evolutionarily, seeking changes in the electoral legislation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to unlock the possibility of reform of the party system.

Schmidt began by flirting with the Croats, thereby setting traps for Dodik. Why with the Croats? – Schmidt’s proposed electoral reform deliberately favoured Croatian parties and reduced the degree of participation of Bosnian voters within the joint Bosniak-Croat federation. This decision, of course, caused discontent among the Bosniaks. Still, on the one hand, it guarantees the support of the Bosnian Croats and Croatia itself, a member of NATO and the EU. On the other hand, it does not follow the lead of the most radical Croatian forces insisting on creating a new (third) federal unit within Bosnia. The mosaic of interests has developed such that Milorad Dodik supports the desire of the Croats to find their own ethnic unit, which is likely to complicate the decision-making process further. In return, the Croatian minority in BH, through its channels of influence in Croatia, which is a full member of the EU, is blocking EU sanctions against Dodik himself.

Schmidt’s plan was probably to first play along with the Croatian minority and reduce Milorad Dodik’s influence over them. And then, having achieved a change in power in the Republika Srpska, for example, by removing Dodik from his post, push all parts of BH to other political reforms necessary for EU membership. To support this plan, Brussels granted candidate status to Bosnia and Herzegovina at the end of 2022. Most likely, the American sanctions imposed against Dodik and his entourage are working towards the same plan, making it possible to restrain the separatist aspirations of the leader of Republika Srpska and contrast him with the remaining two parts of BH.

To ensure that Croatia definitely stops supporting Dodik at the EU level, Schmidt must also help the Bosnian Croats achieve a new model for their representation in the Bosnian-Croat federation. Such a model should also suit fairly radical Croatian nationalists who dream of a third entity. Suffice it to recall how, in 1993, Croatian troops attacked Muslim units and territories and began to create on the lands they conquered a Croatian analogue of the Republika Srpska – the monoethnic Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia. Thanks to the rebuff of Muslim forces and the pressure of the West and the Islamic world on Croatia, the parties were able to reconcile. The Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia was dissolved, uniting Bosniaks and Croats in one entity – the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

For now, Schmidt’s strategy only satisfies the Croatian minority. Despite the dissatisfaction of the Bosniaks, Schmidt’s main task is to unite representatives of the Bosniaks and Croats and create a united front to counter the pro-Russian and separatist sentiments of Milorad Dodik. The Bosniak-Croat Front will, in the future, be interested in strengthening the central government in Sarajevo and weakening the autonomy of the Republika Srpska. Only after the nationalist and separatist forces of Milorad Dodik have been replaced by more moderate ones will Bosnia be able to begin the reforms necessary for its European future truly.

The stakes are rising

At the end of July 2023, the United States imposed sanctions against several high-ranking associates of Milorad Dodik: Prime Minister of the Republic Radovan Viskovic, Speaker of Parliament Nenad Stevandić, Minister of Justice Milos Bukejlovic, as well as against member of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina from Republika Srpska Zeljka Cvijanovic. These sanctions are already the second package of measures the United States is taking against Dodik and his circle. Earlier, on January 5, 2022, Washington imposed sanctions against Dodik. The justification for the sanctions notes that Washington imposed restrictions due to the law adopted by the Republika Srpska, which allows decisions of the Constitutional Court that are binding on all parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina not to be applied on its territory.

Let’s recall that in September 2022, the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina ruled that all state property of the confederation is in state ownership and cannot be appropriated by the authorities of either of the two entities. Despite this, on December 28, the RS Parliament adopted a law on real estate, which directly refuted the conclusion of the Constitutional Court. According to Dodik, all real estate in Bosnia and Herzegovina does not belong to the state but to entities. After the decision of the RS Parliament, the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina intervened again and took temporary measures that blocked the law. Then Dodik threatened to separate the Republika Srpska from Bosnia and Herzegovina and then personally initiated the RS law allowing the decisions of the Constitutional Court, which are binding on all parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, not to be applied on its territory.

The Prosecutor’s Office of Bosnia and Herzegovina brought formal charges against Dodik and initiated a trial against him. The Bosnian Serb leader is accused of failing to implement decisions of the Constitutional Court and ignoring high representative Christian Schmidt. The court intends to obtain a sentence for Dodik (up to five years in prison), followed by a ban on public office and engaging in politics in general.

Subsequently, the High Representative, Christian Schmidt, intervened in the matter and, based on his powers, repealed the RS law on disobedience to decisions of the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In addition, he introduced changes to the country’s Criminal Code, according to which actions to violate the constitutional order and failure to comply with the decisions of the high representative are now classified as criminal offences. “We will not accept any of his (Christian Schmidt’s) decisions. And suppose the prosecutor’s office and the court of BH begin to comply with them. In that case, the Republika Srpska will cease to recognise both the prosecutor’s office and the court,” announced RS President Milorad Dodik. And he threatened: “Before the end of the year, we may hold a referendum on an important issue.” Milorad Dodik has repeatedly called the issue of independence of the Republic of Serbia and reunification with Serbia the most important for the Bosnian Serbs.

Schmidt’s intervention only provoked Milorad Dodik and intensified the confrontation. Thus, Dodik ordered the RS police to establish control of the administrative borders with another part of the country – the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Then, he announced that he would soon ban the activities of the Prosecutor’s Office and the State Agency for Investigation and Protection of Bosnia and Herzegovina on the territory of Republika Srpska. And then he turned to the prosecutor’s office in Banja Luka to initiate a criminal case against the High Representative himself, Christian Schmidt. The conflict began to acquire a geopolitical character. The Russian Embassy in Sarajevo declared that this is a rational result of unlawful actions of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Constitutional Court and that the Court did not rule out some external influence on the judges. The West, following the central authorities of BH, regarded the actions of the Republika Srpska leadership as an attempt at a coup d’etat – more precisely, as “a blow to the Dayton Agreement and the country’s constitution.” In its special statement, the US State Department fully supported Christian Schmidt’s actions.

All these statements meant one thing: the geopolitical component of the crisis in Bosnia will only grow.

The degree of confrontation between the President of the Republic of Serbia and the central authorities and Western representatives in Bosnia was sharply increased by the celebration of Republika Srpska Day on January 9. The Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina declared this holiday illegal three times, and the Venice Commission called it discriminatory. On this day in 1992, the independent Republic of the Serbian people of BH was proclaimed, which local Muslim Bosniaks and Croats consider the prologue to the subsequent bloody Bosnian war, ethnic cleansing and genocide.

In December, Christian Schmidt warned the RS leadership that celebrating the Republic Day on January 9 is a criminal offence and called on law enforcement agencies to take appropriate measures. In response, Milorad Dodik announced that “there is no force that can disrupt the celebration.” It took place in a demonstrative way – with a parade and a procession of thousands in Banja Luka. In addition to the RS police units, the Russian “Night Wolves” bike group took part in the celebration. In addition to the symbols of the Republika Srpska itself, the demonstrators carried the flags of Serbia and Russia.

The United States also voiced its attitude towards the celebration of January 9 unambiguously. On the eve of its holding, two American Air Force F-16 fighters flew over the territory of Bosnia. Officially, the action took place as part of bilateral exercises with the Bosnian armed forces. The American Embassy in Sarajevo stated that the exercises “demonstrate the US commitment to the territorial integrity of Bosnia and Herzegovina amid anti-Dayton separate actions.”

On January 17, the day when the trial of Milorad Dodik was supposed to take place on the third attempt, a lawsuit was filed against him by Ramiz Salkic, a Republika Srpska parliament member from the Party of Democratic Action. He accused the RS president of “organising an illegal celebration of January 9.” “Since one trial is already underway against Dodik in the BH Court, all conditions have been created for pre-trial detention for the suspect to prevent him from committing new crimes and influencing witnesses,” the deputy suggested. However, this requires a separate court decision. The court will have to take into account the fact that at the end of last year, Banja Luka passed a law giving the leaders of the Republika Srpska and its representatives in the central government immunity from prosecution on charges by the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Increasing pressure prompted Dodik to make foreign policy trips, first to Minsk, where he met with Alexander Lukashenko, and then to Kazan to meet with Vladimir Putin. This was their fourth meeting in two years. Dodik was looking for political support in Moscow, and it seems he found it once again. Russia is also interested in supporting the RS President. His position on regional issues practically coincides with Russia’s. Most importantly, Russia needs to prevent the implementation of Western plans to integrate Bosnia into NATO and the EU, which will be impossible without the approval of the Republika Srpska.

Coincidence or not, a month after the meeting between Putin and Dodik at the EU summit, it was decided to begin negotiations with Bosnia and Herzegovina on accession to the European Union, and High Representative Christian Schmidt introduced changes to the country’s electoral legislation as a contribution to future EU membership. The changes include, among other things, the introduction of a pilot scheme for electronic vote counting, electronic identification and digital polling stations. In addition, convicted war criminals will be prohibited from participating in the elections. “I will do today what should have been done years ago. I will guarantee free and fair elections for all citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina,” Schmidt said.

In response, Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik threatened to block the work of the national government of Bosnia and Herzegovina unless changes to electoral legislation introduced by High Representative Christian Schmidt were reversed and Western ambassadors were not expelled from the country.

Another trump card up Milorad Dodik’s sleeve is the referendum on the independence of the RS, which has turned into a “scarecrow” for Bosnian and Western politicians. But as they say, there are questions about its legitimacy. Firstly, such issues are not the competence of the entities and contradict the Dayton Agreements. Secondly, there is a risk that in the event of a small turnout it will simply be recognised as failed. Therefore, the authorities of Banja Luka are trying to change the law on the referendum, in particular, to remove the rule according to which, in order to win, it is necessary to obtain a positive response from the majority from everyone who has the right to vote in the RS, replacing it with a simple majority.

Apparently, only Dodik himself knows what he will do next. His rhetoric concerning the independence of the RS and European integration has many “inconsistencies”. One day, he says that he is fighting for the expansion of the powers of the RS within BH; the next, he threatens with secession. As for secession, he perfectly understands there will be no international recognition, even from Serbia. Maybe only Lukashenko and Putin, who, being in international isolation, have nothing to lose. Generally, there is nothing new; Dodik behaves like a populist who operates all permitted and prohibited methods just to maintain his authority. And, as the experience and history of BH reveal, the “authority at any cost” principle leads to nothing but bloody conflicts and human tragedies.

The Balkans again resemble a “powder keg”, and indeed, no one wants local politicians and geopolitical actors to get the situation to new “shots in Sarajevo.”