Viktor Orban is one of those leaders whose speeches are instantly picked up by the world media, analysed by numerous experts, and become a “bone of discord” in the political environment. March in Hungary is a special month. Every year, the country widely celebrates the anniversary of the start of the revolution of 1848–1849, and against this background, political life usually revives sharply. Viktor Orban also “perked up.”

He announced a new attack on the European Union in his celebratory speech. He noted that if Hungarians want to maintain their freedom and independence, they must “occupy” Brussels in the European Parliament elections and change the European Union.

Orban’s harsh rhetoric towards the European Union is not news but rather a reason to mobilise his electorate as much as possible on the eve of the elections to the European Parliament, where he counts on the success of his Fidesz party. For many years, Viktor Orbán remained the main anti-hero of the European Union and, apparently, never objected to such a title. Many even call his conflict with the EU ideological. However, an analysis of his political activities demonstrates that this is not entirely true.

First, Hungary’s Prime Minister is a pragmatist who is only interested in power and extracting maximum political dividends here and now. This is confirmed by his political position, which fluctuated along with the political situation and public sentiment. Having started his career as an absolute democrat, the future leader of Hungary moved to the conservative camp and became one of the embodiments of the right-wing turn in European politics and a prominent leader of the “Eurosceptics”.

In this article, Ascolta studies the socio-political situation in Hungary and also studies the political transformations of Viktor Orban, thanks to which he managed not only to maintain his influence on internal political processes in Hungary but also to become one of those leaders of the European Union whose word remains decisive in many questions.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

Evolution of a leader: from ultra-liberalism to Euroscepticism

The day of June 16, 1989, is remembered by many in Hungary. Particularly impressive was the performance of the young and then unknown 25-year-old leader of the Fidesz party, Viktor Orban. The slogan of the seething Budapest street in the autumn of 1956 was “Russians – home!” it sounded again in the summer of 1989 in a speech by a young politician, especially boldly and loudly. The day after Viktor Orbán’s speech, his name first appeared on the pages of newspapers and, since then, has practically never left their front pages.

From the creation of the youth organisation FIDES as an alternative to the Hungarian Komsomol until the victory in the 1998 parliamentary elections, Viktor Orban and his political party had ten years. During this time, a youth organisation of 30 people, known only to a narrow circle of acquaintances, grew into the largest party in the country, which was able to win elections against the Socialist Party of Hungary, the heir of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party. Undoubtedly, this was the merit of the leader. In 1998, the year of his victory in the parliamentary elections, Orban was 35. He became the youngest Prime Minister of Hungary in the country’s entire history, but even then, he was a reasonably experienced politician.

However, the time for Fidesz did not come immediately. For some time, the party remained in the shadow of its senior comrades in the opposition movement, primarily the Hungarian Democratic Forum under the leadership of József Antall and the Union of Free Democrats under the leadership of János Kis. These two parties won the largest number of votes in the first free parliamentary elections in 1990 and formed a Christian liberal government. The results of Fidesz’s first free elections in 1990 were not very comforting – 8.95% of the vote, fifth place. And this is despite the help of American “PR people” working through the George Soros Foundation.

The excessive radicalism of young reformers scared off voters. Therefore, many preferred to give their votes to the “quiet force,” and Fidesz remained in the opposition. Orban himself and his entourage concluded that society no longer accepts radical anti-communist and anti-Soviet rhetoric and needs to move away from it. From this moment on, young liberals and Orbán, partly instinctively and partly consciously, began to move away from both radical anti-communism and radical liberalism.

The 1994 elections did not fare well for all the right-wingers, including the Fidesz party, which received only 7% of the vote (after 8.95% in 1990). After the failure of the right-wing forces, the pendulum of sympathy among Hungarian voters swung sharply to the left. Fidesz again found itself in opposition. The new defeat affected the party leader so strongly that he was ready to leave politics for business. Viktor Orban completely disappears from the public space and goes into the shadows for some time. However, after a few years, Orban returns and gradually demonstrates new political ambitions. The party is confidently gaining strength, uniting small right-wing parties and continuing to shift towards the political centre.

This time again, Orban himself is the initiator of the changes. An extraordinary polemicist-fighter, a politician who can rally a reliable team around himself, also has ebullient energy. Actual, many at this time begin to notice in the leader a tendency towards leadership and individual decision-making, rejection of criticism and alternative opinions. As a politician, he becomes tougher. Now it is FIDES – Hungarian Civil Union (FIDESZ – Magyar Polgári Szövetség). At first glance, a slight change in the name of the party, in fact, reflected a lot. And the departure from liberal ideology with the transition to the position of Christian democracy, the unification of right-wing parties, and simply the maturation of yesterday’s 20-year-old students, who, in turn, became fathers of families.

The massive disappointment of Hungarian voters, first in the right and then in the left parties, by and large, paved the way for the victory of Fidesz in the 1998 elections. By this time, the country was already heading towards joining NATO and the EU, receiving an invitation from these organisations in July 1997. In the spring of 1998, negotiations began between Budapest and Brussels, which lasted six years. At the turn of the century, the question of “returning to Europe” became the main topic of the day in Hungary. Hungarians expect a specific miracle from reunification with Europe, demonstrating almost the same sentiments that have existed for many years in Ukrainian society. Average Hungarian citizens were utterly confident that the standard of living in their country would approach the standard of living in Germany or France, that salaries and pensions would rise to European levels, and that they could buy a car and an apartment quickly rather than saving for them all their lives. Notably, in the wake of such expectations and an inflated level of populism, the Fidesz party had to lead the country into the European Union.

In the May 1998 elections, Hungarian voters again changed power in the country, voting not so much for the right as against the left and liberals, who did not live up to their hopes for a better life. For the next four years, FIDES headed the ruling coalition, and its leader, 35-year-old Viktor Orban, became the youngest prime minister in Hungarian history. The winners, however, were too early to rejoice. The economic situation has not gotten any easier. Despite the influx of foreign capital, including through the massive privatisation of Hungarian enterprises, stagnation continued. The 1989 level was not achieved either in terms of GDP or in terms of personal income. Complex negotiations on integration into the EU began. Reforms were needed in healthcare, education, infrastructure, and the budget. But, despite all the promises, the reforms were never carried out. Instead, there was a total change in the managerial elite at the top and middle levels; new, young, but not always competent people came to power. Management efficiency has noticeably decreased. The public debt increased again during the Fidesz government and, with it, the budget deficit.

Fidesz was defeated in the 2002 elections, and for the next eight years, power in Hungary was exercised by the socialists in an alliance with the free democrats. Fidesz will return to power only in 2010, and in many ways as a different party. Hungary has also become different in eight years.

In the right-wing camp, including Fidesz, a sense of urgency and determination was palpable even before their victory in the elections. They interpreted the political processes as a betrayal by the left and liberals, who they believed had sold the country to local and foreign oligarchs, driven it into debt, and handed it over to foreign capital and globalist structures. Fidesz’s agenda was then filled with messages about ‘restoring order,’ economic sovereignty, the priority of national capital, and strengthening the role of the church in public life. These were not just words but a call to action in the coordinate system of ‘national conservatism,’ from which all significant legislative innovations in Hungary in recent years originate, including those that cause criticism of the EU.

Fidesz’s victory in 2010 was predetermined, and for the first time in the history of independent Hungary, the party received a constitutional majority in parliament – and since then, power has not been given up to anyone. Viktor Orbán said, “Today, Hungarians made a revolution at the ballot box.”

Strengthening the “vertical of power” and a right turn

Such a “revolution” was made by constitutional methods only. Although the vote was primarily a protest, Orbán willingly presented himself as the saviour of the nation, who could eradicate corruption, revive the economy, rebuild Hungary and, finally, give the population a decent standard of living, which had not been achieved either by privatisation or by joining the European Union. Under these slogans, the Fidesz party began a large-scale reform of political institutions and, at the head of a coalition with the Christian Democratic People’s Party, tried to take control of all branches of government. Hungary’s executive, legislative and judicial branches have gradually strengthened ties between themselves and the ruling political force led by Viktor Orbán. Now, these branches of government, which should be independent, support each other and Fidesz – sometimes unobtrusively and sometimes openly.

The 2011 constitutional changes became the first crack in the relationship between Brussels and Budapest. First, Orbán’s team attacked the independence of the judiciary. Taking advantage of its majority in parliament, Fidesz increased the number of judges on the Constitutional Court from 11 to 15, appointing four of its own judges to new seats. Then, they lowered the mandatory retirement age for judges and prosecutors, freeing up hundreds of positions for her supporters. Later, a National Judicial Office under Orban’s classmate Tunde Hando was established. It can veto promotions and influence which judges hear which cases.

In 2013, the Constitutional Court rejected some of Fidesz’s new laws, including one that threatened various churches with the loss of official status. In response, so that the Constitutional Court “does not get in the way,” new amendments were made to the Constitution. These amendments withdrew the Constitutional Court from the political and legal field. Since then, the Court, like the country’s president who just signs the laws, cannot influence their content. Thus, almost unlimited authority is concentrated in the hands of the government and the parliamentary majority.

In addition, the new Constitution renamed the Republic of Hungary simply to Hungary. From then on, it declared that the Hungarian state would take responsibility for protecting Hungarian communities abroad and preserving their Hungarian identity. This was enough to worry some of the neighbours, especially Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Serbia, whose relations with Hungary were not too friendly anyway.

In addition, critics of the new Constitution remarked that it definitely established conditions for discrimination against various population groups. For example, one of the articles states that all residents of the country constitute a single Hungarian nation – thereby discriminating not only Roma but also other national minorities. Another example that infringes on the rights of the LBGT community is that it emphasises the sanctity of the family, which the document understands only as a union of a man and a woman. Finally, the Constitution guarantees child protection “from the moment of conception,” not from the moment of birth. According to some critics, this could call into question the legality of abortions, which currently are legally allowed in the country.

Viktor Orbán loves superlatives. In 2010, he called his victory “a revolution at the ballot box,” in 2014, it was “an epoch-making and incredible success, the significance of which is still impossible to assess today,” and in 2022, he declared that “his victory can be seen even from the moon, otherwise, which is in Brussels.” The secret of his electoral success lies, among other things, in his painstaking work with election legislation. It is no coincidence that since 2010, FIDES has won every election because it has always paid great attention to preparing a regulatory framework that “facilitates” the victorious electoral march of the party in power.

First, the new electoral law reformatted the constituencies towards their consolidation, the lower threshold for turnout was abolished, and the right to vote was granted to the approximately two million ethnic Hungarians who are citizens of Romania, Slovakia, Serbia and Ukraine and who are overwhelmingly Fidesz voters. They are allowed to vote by mail. At the same time, about 350 thousand Hungarian citizens living in the West and less willing to vote for the ruling party must vote in person at embassies or consulates. This explains how Fidesz won 67% of parliamentary seats in the 2018 elections, maintaining its majority despite receiving just under half the popular vote. Because the system is so well-designed, the party does not need to stoop to rigging elections, as crude autocracies do. Their “system of national cooperation” is extremely sophisticated. In 2018, the National Elections Office invalidated thousands of mail-in votes because the security tape on the envelopes had been tampered with. In response, the government repealed the law requiring protection from unauthorised access.

It seemed that in 2022, Viktor Orbán’s electoral triumphs would end. Moreover, on February 24, Russia invaded Ukraine, and many of the representatives of the Hungarian opposition saw this as an opportunity. It seemed that now, a person who had supported the autocratic leader of Russia who started the war for many years would not be able to win the elections. However, the war in Ukraine had the opposite effect on the opposition, which consolidated into a coalition of six parties. By using the “peace” agenda, Fidesz convinced the majority of Hungarians that it was for peace and the opposition was trying to drag Hungary into war. How this happened remains a question. Moreover, the ruling Fidesz party was not confident of its victory until the very end. Therefore, as experts note, administrative resources were widely used.

The government mandated additional payments: pensioners, married couples and children received subsidies; tax holidays and income tax refunds were provided for many people. “The state’s concern” was exhibited even through utility bills. They always indicate two amounts: the one that needs to be paid and the one that the government supposedly saved thanks to the decision to control prices. The essence of the government program, which the Fidesz party initiated in 2013 and called “rezsicsökkentés,” is that the government dictates to utility companies to reduce their prices.

Fidesz did not spare financial resources for the election campaign. As Transparency International notes, in March 2022 alone, Fidesz spent 3.1 billion forints (8.4 million euros) on an advertising campaign – this is three times the limit provided by law. Fidesz and the opposition also had unequal access to the media. Since the start of the election race, opposition prime minister candidate Peter Marki-Zay has received only five minutes of airtime on state television. At the same time, Prime Minister Viktor Orban was constantly on the information agenda on all government channels. Moreover, the media were the subject of particular “concern” of Viktor Orban. After losing the elections in 2002, he realised that he did not have a reliable “rear” in the form of the media. Orban and his associates began to create this “rear” while still in opposition, and when they came to power, they gradually took over the “lion’s share of the media.” Since coming to power in 2010, Orbán has begun “reforming” the “fourth estate.”

Using the majority, Fidesz passed through parliament a law on mass media. According to it, a special committee was created to control the activities of the press. This committee was composed exclusively of Orbán supporters. Orbán’s first serious attempt to establish control over the media also turned into the prime minister’s first grandiose humiliation. The European Union opposed the law, which had already been adopted by parliament, and changes had to be made. Next, the Orbán government began to turn state media into organs of its propaganda. This was the case with the MTI news agency, and regional newspapers, which lacked reporters, became channels for MTI’s pro-government messages, and it is from these newspapers that Orbán’s voters in small towns receive their news. Hungary’s television channels and radio stations are also almost entirely controlled by the government. Today, the ruling party is “served” by state resources and nearly 500 media outlets, which have been acquired by businessmen loyal to Fidesz over the years. Thus, the largest opposition newspaper in the country, Nepsabadshag, was bought out and closed in 2016. A company acquired it allegedly linked to Orbán’s childhood friend Lorinc Mészáros, who is the country’s second most prosperous businessman.

Independent media is currently limited to sites with a small readership in Budapest’s liberal bubble. In addition, Orban’s position was significantly strengthened by the fact that he again presented himself as the “defender” of the Hungarian people, and the controlled media successfully dispersed this message. In a word, the whole complex of reasons led to the fact that Fidesz received 135 out of 199 seats in parliament.

According to the election results, the united opposition had only 57 seats. This gap is even more comprehensive than four years ago when the opposition did not have a coalition. Summing up the election results, Viktor Orban said: “This victory will be remembered, perhaps, for the rest of our lives. Because in our battle, we were in the minority like never before: the Hungarian left and the international left on all sides, the bureaucrats of Brussels, all the money and organisations of the Soros empire, the leading international media and, in the end, even the president of Ukraine. Never before have we faced so many opponents at once. But despite their huge money and superiority, when we are together, we are unstoppable.”

The “Orbanomics” – salvation or disaster

Hungary’s economy, often referred to as “Orbanomics”, has also been a major concern in the EU. From the first days of his premiership in 2010, Viktor Orban announced the start of a new economic policy.

One of his first steps was adopting the Law on the National Bank, which provided for its nationalisation with reassignment from the IMF to national authorities. Other steps soon followed the quick parting with the IMF. Following the USD 1 bln bank tax imposed on Western financial and insurance institutions operating in the Hungarian market, the “Robin Hood tax” was imposed on major Western energy, telecommunications and trading companies. Speaking in parliament, Prime Minister Viktor Orban said that the government can no longer increase the tax pressure on ordinary citizens of the country and small businesses, which already bear a severe tax burden. Therefore, the time has come when big business must take on an additional share of social responsibility in solving the country’s problems. This includes large companies with foreign capital, which had large tax benefits in Hungary for a long time.

Following the bankers (70% of the Hungarian banking sector at that time was under the control of foreign capital), energy workers (Shell, BP, etc.), mobile operators and retailers – owners of large retail chains (Auchan) contributed their first billion dollars to the general anti-crisis basket. , IKEA, Metro, etc.). Energy companies have worked the hardest. Their plan for the year was 70 billion forints or USD 350 mln. Telecommunications companies were to contribute a little less – 61 billion (USD 300 mln). Half of this amount – 30 billion forints, or another USD 150 mln – fell to the share of network traders.

Naturally, there were some protests and grumbling about the new Hungarian taxes. There were also scandals, both with Brussels and with Washington. But Budapest, despite some adjustments, still stuck to its line. This also applied, by the way, to the national currency, the Hungarian forint. After coming to power, Viktor Orban stated that Hungary would switch to the euro when its public debt dropped to 50% of GDP, and then began to argue that to abandon the forint, Hungary’s GDP per capita would need to be brought to 90% of the eurozone average. For a country to join the eurozone, the approval of 2/3 of parliament members is required, that is, a vote from Fidesz. However, the Hungarian authorities deliberately preserve the forint to carry out devaluations if necessary, increasing the competitiveness of their economy. This policy has its own price – high inflation and growing external debt, but it allows Hungary to maintain a distance from the EU.

Orbanomics also fits nicely into the authoritarian toolkit. Sociologist and former Hungarian education minister Balint Magyar argues that the state under Fidesz is a means of capturing the economy and distributing flows and income among its own. He calls Hungary a “mafia state.” And some experts argue that Orban is akin to Putin in this regard. He created something like “Putinism-light” – a light version of Putinism. It is not as repressive as in Russia, perhaps precisely because Hungary is a member of the European Union: Orban is still unable to rampage to the extent of post-Soviet authoritarianism. The kinship is that Orbán and his clan, the businessmen and bureaucrats associated with him, have significant economic influence. These affiliated structures have taken over a significant part of the economy, all its more or less tidbits.

The scheme is approximately the same to the Russian one – capitalism with a very strong mafia-clientelist flavor. Six years after joining the European Union, when Hungary began to receive generous development subsidies from EU funds, the government carefully ensured that the money ended up with people close to it. As noted by the former deputy of the Hungarian Central Bank, Julia Kiraly, the Prime Minister and his entourage control enterprises and companies that make up about 30% of the country’s GDP. This is the service sector and tourism, catering, agriculture and so on. Orban himself, categorically rejecting accusations of corruption, calls the enrichment of people close to him “the creation of a national bourgeoisie in Hungary.” However, according to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, Hungary ranks last among EU countries.

Of course, it should also be noted that Hungary has achieved undeniable economic success. From 2010 to 2020, GDP grew by almost 30%, from $120 billion to $161 billion; The country’s exports increased by 47% to 104 billion euros. The rate of economic growth in 2018-2019 reached 5% per year; unemployment fell from 12.5% in 2010 to 3.3% in 2019. Over 10 years, 800 thousand new jobs have been created in the country, moreover, in innovative sectors of the economy.

German automobile giants BMW, Audi, and Mercedes-Benz came to Hungary and built their factories. Budapest could soon become a world centre for producing batteries for electric cars. In addition to Chinese investments, South Korean Samsung is already building its third plant in Hungary, which is expected to produce new 5th-generation prismatic batteries.

However, several economic problems associated first with the pandemic, then with rising energy prices, the war in Ukraine and the 2022 sanctions policy towards Russia brought serious financial problems to Hungary. Forint, the country’s national currency lost 13% of its value against the euro, more than in neighbouring Poland, Slovakia or Romania. At the end of the year, inflation in Hungary became one of the highest in Europe – 22%, and in January 2023, inflation in the country reached a 27-year record of 25.7%. The level of public debt again reached 75% of GDP. In 2023, the Hungarian economy went into recession. There are no final official data, but according to preliminary estimates, it decreased by 0.4%. This happened against the backdrop of the EU economy growing by 0.6%. The economies of other Central European countries also grew: Poland – by 0.2%, Slovakia – by 0.5%, and Romania – by 2.2%.

The reason for the fall of the Hungarian economy was the weak indicators of domestic consumption, which fell by 2%, and a reduction in industry and construction. The profits of the country’s citizens, based on the results of 2023, also decreased as inflation reached 17.6% and overtook the wage increase by 3.3%. Price growth in Hungary was the highest among all EU countries. Against this background, the relationship between the EU and Budapest continued to deteriorate. Hungary faced a severe financial blow after the pandemic. The EU has decided to create a new €750 billion recovery fund to reduce the economic damage in the hardest-hit member states. Donor countries, that is, those who contributed more to this fund than they received, in return put forward a demand to develop a new rule for the use of budgets in EU legislation – the “preconditions mechanism”. This mechanism would make it possible to limit the budgeting of a particular EU country from general funds if it violates the rules of the European Community. The decision on this may not be made unanimously; a vote of at least 15 EU countries, whose population totals at least 60% of the total population of the entire union, will be sufficient.

For the first time, the European Commission began to develop parameters for the actual use of this mechanism exclusively in relation to Hungary and not to Poland. As a result, this allowed the EU to freeze payments to Hungary from the general budget. For Hungary, the “losses” amounted to more than 20 billion euros: this is exactly the amount that was provided for it in the EU budget for 2021-2027. In addition, funds from the EU fund for economic recovery after coronavirus were actually frozen for Hungary. Budapest’s deprivation of more than €25 billion from these two sources alone was therefore significant: by comparison, Hungary’s nominal GDP in 2021 was €184 billion.

“The Gatherer of the Nation” or a national populist?

The European Union has often harshly accused Viktor Orban and his supporters of nationalism and populism. This is mainly due to the position of the Fidesz party on the situation of the Hungarian national minority living in countries neighbouring Hungary – Serbia, Romania, Slovakia, and Ukraine. According to the Treaty of Trianon of 1920, which became part of the Versailles system, Hungary lost approximately two-thirds of its former territories and a third of the population living in these lands. For a hundred years, the “Trianon trauma” – the syndrome of a divided nation – has remained a sore point in the Hungarian national consciousness. In the policy of the Fidesz party, the issue of the Hungarian minority in neighbouring countries is one of the critical areas of domestic and foreign policy.

Themes related to the “gathering of the nation” and the distribution of passports to ethnic Hungarians are closely intertwined with rhetoric dedicated to demographic processes and Budapest’s position regarding illegal migrants. Let us recall that in 2015, the influx of illegal migrants from Africa and Asia into EU countries caused an acute crisis. Then, the coalition government of German Christian Democrats and liberals decided to accept migrants from Asia and Africa and proclaimed an “open door” policy for the entire European Union. Orbán was the only European politician who spoke out strongly against uncontrolled migration to EU countries from the beginning. On this basis, he also had a personal conflict with George Soros, who supported Viktor Orban at the dawn of his political career. Since then, the Hungarian Prime Minister’s colleagues from Western European countries have constantly criticised the Fidesz leader, accusing him of nationalism.

Nevertheless, the position of the Hungarian Prime Minister during the migration crisis received support and approval in the region of Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. On his side were the leaders of the Visegrad Four countries, which, in addition to Hungary, includes the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia, as well as Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Serbia, and Croatia, who were forced day after day to hold back the onslaught of illegal migrants. Orban himself ordered the construction of a 175-kilometer barbed wire fence along the border with Serbia, and has since scorned the EU’s doomed attempts to deal with the chaos created by the continent’s immigration crisis.

In 2017, the European Parliament approved a resolution calling for Hungary to repeal laws preventing migrants from entering the country. The adopted resolution contained a warning that, in the event of Budapest’s failure to comply with Brussels’ conditions, Article 7 of the EU Treaty could be invoked concerning Hungary – i.e. internal restrictions have been introduced aimed at an EU member state that violates the fundamental rights of European citizens. As a punishment, such a country may be temporarily deprived of its voting rights in the Council of the EU; certain financial sanctions may be applied to it. Orbán remained unconvinced and said that the migration crisis of 2015–2018 was his “first disappointment” in the European Union since Hungary joined it in 2004.

Pragmatic multi-vectorism

Hungary’s foreign policy, like its domestic policy, is firmly subordinated to frank pragmatism. Viktor Orbán uses various techniques and tools to pursue his goals. “Image of the Enemy” is one of them. Over the years, Viktor Orban and his party pragmatically “defended” Hungarians from: “American billionaire and philanthropist George Soros”; “Roma and migrants”; “NGOs and LGBTQ+ representatives.” And finally, Brussels, which, at Orban’s suggestion, is perceived not as the European Union (many in the country welcomed its entry into it) but as a hostile force that is trying to subjugate the Hungarians.

Today, Orbán’s followers are looking for the origins of this confrontation in the history of Hungary, noting that in various periods, from the Great Hungary of Arpad and Matthias Corvinus to the periphery of the Ottoman Porte and the Austrian Habsburg Empire, the desire to maintain independence remained characteristic of Hungary: in judgments, ideas, foreign policy. The experience of an alliance with Hitler during the Horthy regime and then the Soviet occupation, which lasted until the early 1990s, made the Hungarian vision of the world and themselves in it similar to the Israeli one: “We don’t trust anyone when it’s profitable, we can deceive anyone, and this is justified because everyone is guilty of treating us unfairly.” Orban himself likes to answer his opponents from the EU in the same spirit: “… at one time Budapest did not allow either Vienna during the dualist Austro-Hungarian monarchy or Moscow during the existence of the “socialist camp” to interfere in its affairs, and now it will not allow Brussels either during the Eurocamp.

The aggravation of the EU-Hungarian relations had several peaks. The first occurred in 2015-2017 when Budapest adopted laws against illegal migration and held a referendum on mandatory EU quotas for the resettlement of migrants. After Orban’s victory in the 2018 parliamentary elections, the confrontation between Budapest and Brussels reached a new level. In 2019, Viktor Orban challenged the influential head of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, by linking his name with the name of George Soros, who funds public organisations that help migrants. That same year, “advertising” billboards appeared all over Hungary depicting Juncker alongside Soros with the caption: “Who knows what else Brussels is preparing?” and “They want to weaken EU states.” After this, the European Commission initiated legal proceedings against official Budapest due to the policy of the Hungarian authorities towards non-governmental organisations working with migrants. The European Court later ruled to repeal this law (as well as a package of legislative measures called “Stop Soros”, which criminalises assistance to migrants, including when filing an asylum request).

The reason for another round of tension between Budapest and Brussels was the coronavirus pandemic. At first, nothing foreshadowed a severe conflict. Still, at the end of March 2021, in an interview with the Kossuth radio station, Viktor Orban said that the “vaccine story” became his “second disappointment” in the European Union. At the start of the vaccination campaign, Budapest announced that it intended to pursue a “multi-pronged policy” in procuring vaccines. On January 21, 2021, Hungary, contrary to the recommendations of Brussels, was the first in the European Union to approve the use of the Russian Sputnik-V vaccine. Government media distributed pictures of Orban himself being vaccinated with a Chinese vaccine. The saga of Russian and Chinese vaccine purchases showed how the populist Orban demonstrated to the Hungarians his ability to find quick technocratic solutions to urgent problems against the backdrop of a slow response from Brussels bureaucrats.

However, all previous episodes of the confrontation between Budapest and Brussels faded against the backdrop of a powerful campaign that began in the European capital after, on June 15, 2021, the Hungarian parliament, at the instigation of the Prime Minister, overwhelmingly adopted the so-called “Law on the Prohibition of Gay Propaganda.” A few days after the law’s adoption – on June 25, 2021, at the EU summit in Brussels – Hungary and the prime minister who represented it were literally branded with disgrace. The head of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, said that the “disgusting law” adopted by the Hungarians contradicts the basic principles of the European Union and should either be immediately repealed or adjusted. She promised that if the Hungarian authorities did not back down, the body she headed would use all means available to it to “bring some sense” to Budapest.

Another peak in tensions came with the EU’s decision to introduce a new mechanism to control the distribution of pooling funds, which was a partial response to the pandemic. Brussels decided to link the allocation of money from the general budget to compliance with the principles of the rule of law. This caused protests from Warsaw and Budapest. The parties tried to block the approval of the EU budget, create a post-pandemic recovery fund and some other initiatives, and challenge the new measures in court. However, in February 2022, the EU Court sided with Brussels.

In his search for allies to oppose the EU, Viktor Orban looked for various configurations and combinations. Within the EU, he hatched plans to make the informal political union of Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Hungary, called the Visegrad Four, the bearer of new tendencies that are more sovereign, nationally conservative and critical of Brussels. Before the victory of democratic forces in Poland with Warsaw, it was indeed possible to plan some kind of unification, relying on the proximity of political regimes. Orban had an easier time with Poland because the leader of the Law and Justice party, Jaroslaw Kaczynski, made it his main principle to keep Poland as far away from the European Union as possible.

After forming a government led by Donald Tusk, such an alliance has become impossible. However, unexpectedly, after the victory of Smer-SD in the parliamentary elections in Slovakia, Viktor Orban had a new ally in the person of the country’s Prime Minister Robert Fico. If the Poles joined forces with Orban for ideological reasons, then in the situation with Fico, the willingness to cooperate is based on other factors. Fico’s first steps showed he was pursuing a much more cautious policy than his Hungarian colleague. In such a company, reviving the Visegrad group in the way Orban needs is impossible.

Therefore, it is absolutely no coincidence that Orban went to Florida for support, where the famous “Eurosceptic” and possible winner of the US presidential election, Donald Trump, lives. Viktor Orban has long had friendly relations with the Republican leader. The political views of the two leaders are also similar. The America First program is very close in spirit to the Hungarian Prime Minister, and Viktor Orban was the first European Prime Minister to support Trump during his first presidential campaign. He also called on Trump to return in 2024 and called the court cases against the former president a “witch hunt”, reflecting how Orban blames the EU for democratic backsliding in Hungary.

“Trump’s return is a prerequisite for strong and rapid peace on the European continent. From the Hungarian and the world’s point of view, Trump’s return is more than welcome,” Orban said at a diplomatic forum in Turkey.

And Trump did not spare epithets addressed to the Hungarian prime minister: “He’s the boss. No – he’s a great leader, a fantastic leader.” True, sometimes the “love” for the Hungarian politician overwhelms Trump so much that he does not remember the country in which Orban heads the government: “He is probably one of the most powerful leaders in the world. He is the leader of Turkey.”

Of course, the trip to see Trump in March 2024 showed that Orbán had gone for broke. He understood perfectly well that the democratic administration would not forgive him for such an act. Throughout the visit and after it, the Hungarian prime minister used every opportunity to emphasise that he had finally put an end to the possibility of cooperation with the current government in Washington and that he was ready for serious problems if Biden was able to be re-elected.

For Orban, a meeting with Trump is another opportunity to show the European Union that if the Republican leader wins, Hungary will replace Poland as Washington’s main strategic ally and become a kind of bridge between Europe and the United States. And while leaders from across Europe are trying to reconnect with Trump’s team, few have the direct line and air of bonhomie that Orbán has with the former president.

But the Hungarian authorities were not only looking overseas. Having initiated a turn in Hungarian foreign policy under the slogan “opening up the East,” Orban has done much to attract investment from China. Yet, at the same time, he has begun to court Moscow. We have already noted that Viktor Orban is a pragmatist who acts exclusively in his interests and only then in the interests of Hungary. Eventually, this determines his political course. Adapting to the situation or, in other words, changing his views is a common thing for Viktor Orban. Just as he evolved from a liberal to a conservative, in the same way, he turned from an enemy of Russia into her friend.

Suffice it to recall how, at the dawn of his political career, he harshly criticised Russia: he called the decision of the socialists, then in power, to support the South Stream project a betrayal of the country and called other European governments “Putin’s puppets.” “The younger generation that supports us must not allow Hungary to become the most fun barracks of Gazprom!” – Orbán said in 2007, paraphrasing a Soviet joke that Hungary is the most cheerful barracks of the socialist camp. However, in 2009, Orban radically changed his views. In December 2014, Hungary officially signed the first major contract with Russia to modernise the Paks nuclear power plant, which caused massive criticism in the European Union. By that time, Russia was already under economic sanctions after the annexation of Crimea and the crash of flight MH17.

Unlike other former socialist countries, Orban has never tried to find an alternative to Russian energy. Paks NPP and Hungarian oil refineries can only use Russian fuel for technical reasons. And, of course, gas… For Russia, it has long become a political weapon. And for every preferential cubic meter, Hungary pays by repeating Moscow’s theses even more diligently than before the full-scale aggression against Ukraine.

Viktor Orban often likes to say that thanks to his foreign policy strategy, he is achieving favourable prices for Russian gas for Hungary. In early February 2022, when the countries signed a new 15-year contract, Vladimir Putin claimed that the price for Hungary was five times lower than the average. But the Hungarians do not know whether this is so: the gas deals’ terms are not disclosed. “According to statistics, until recently, Russia did not provide cheap gas, and Hungary paid the market price. Thus, Russian gas received by Hungary under a long-term contract is one of the most expensive in Europe. From the beginning of 2021 to February 2022, Gazprom raised prices for Hungary approximately five times. For comparison, gas from Algeria received by Italy and gas from Azerbaijan received by Bulgaria are approximately 60% cheaper than Russian gas for Hungary. And even liquefied gas from the United States, which Spain receives under a long-term contract, is slightly more affordable than Russian gas for Hungary. The main reason for Hungary’s connection to Russian gas is the pipeline infrastructure that has developed historically and the lack of access to the sea, which allows for the rapid construction of a gas terminal.

Budapest is interested in cheap gas that can replace Russian gas, but implementing it is technically challenging, time-consuming and expensive. And the gas infrastructure of Europe has historically been built so that Hungarians will be the last to be connected to alternative gas. So, Russian “preferential prices” strongly resemble gas blackmail.

Does Orbán have options? It would be possible to appeal not to Moscow but to the EU, looking for relatively quick, albeit temporary, ways to solve logistics problems and money to solve them. However, until 2014, the EU hung on Russian gas pipelines without problems and increased consumption. Over the next seven years, from 2014 to February 2022, the European Union was in no hurry to reduce consumption of Russian gas, complaining about the selfish pressure of the United States. These factors ensured the gas connection between Budapest and Moscow, with all the political consequences. In addition, a sharp turn towards the EU would mean Orban’s surrender of many positions in his permanent bargaining conflict with Brussels, from which Budapest is seeking concessions for itself. In other words, Brussels and Washington are long-term partners for Budapest, with whom Orban needs to build relationships, ensuring a strong position for himself, including in the eyes of his voters.

Moscow is a temporary, situational and secondary partner, but currently necessary. It gives Orbán space for political bargaining, in which he prances in front of NATO and EU allies “riding Putin,” encouraging them to make concessions. And at the same time demonstrating to voters his inflexibility combined with pragmatism. An attempt to negotiate with Putin at the cost of concessions, including the surrender of Ukraine, from the point of view of Orban, a populist and autocrat based on extreme manifestations of Hungarian national egoism, is quite logical. However, Russia and Putin are only part of the labyrinth in which Orban is trying to pave the way for himself and Hungary.

Hungary is often called the “Trojan horse”, not only of Russia but also China. No other EU country has such close ties with China as Hungary. Budapest has become an essential gateway to the European Union for Beijing. Hungarian representatives in European structures have been opposing EU resolutions that criticise China for many years. For example, in 2021, Hungary blocked the adoption of a joint statement by EU countries that criticised China’s suppression of protests in Hong Kong. The rapprochement with Beijing is evidenced not only by the fact that Hungary is blocking EU resolutions regarding China but also by economic cooperation. Today, the trade turnover between Beijing and Budapest exceeds $10 billion, and Hungary consistently ranks high on the investment map of the largest Chinese companies.

China doesn’t spare any money on its European favourite—China’s annual investments in the country amount to about 3 billion euros annually. First, funds go to the chemical industry, banking sector and telecommunications. According to experts, Chinese investments in the country could soon grow four times and reach 13 billion euros. The improvement in Hungary’s relations with China occurs against the backdrop of their cooling with the EU – Chinese investments in Europe have fallen to their lowest level in a decade. Thanks to this and constructing a new battery gigafactory, Hungary will account for up to 20% of all Chinese investments in the EU in 2022.

True, as experts note, Beijing is pursuing a policy towards Budapest similar to that pursued concerning African countries – it is pouring money on infrastructure and industrial projects, for example, the first plant in Europe of the Chinese manufacturer of electric cars BYD or the railway connection between Budapest and Belgrade, which is being built Chinese companies. However, the real benefit of local businesses is questionable. When China invests, it distributes work among its own companies, while local companies get the remainder.

Thus, only one Hungarian company, RM International Zrt, is involved in the construction/renovation of the Budapest-Belgrade railway, which uses only 15% of these investments and within the framework of the Hungarian-Chinese consortium. The conditions under which the Chinese provide loans are also unfavourable, and “delays” in loan repayments have plunged more than one country into becoming an eternal debtor to China. Before the construction of the BYD plant, Tesla’s global competitor in the production of electric vehicles, China’s most significant direct investment in the Hungarian economy was purchasing the chemical concern BorsodChem in 2011 for 1.2 billion euros.

Hungary is also home to Huawei Technologies’ largest logistics and manufacturing base outside China, despite warnings from the European Commission that the telecoms giant poses a security risk to the EU. The same BYD already has a plant for producing electric buses in the Hungarian city of Komár, and the Chinese company CATL, the largest manufacturer of batteries for electric vehicles in the world, is building a plant in Hungary worth $7.6 billion.

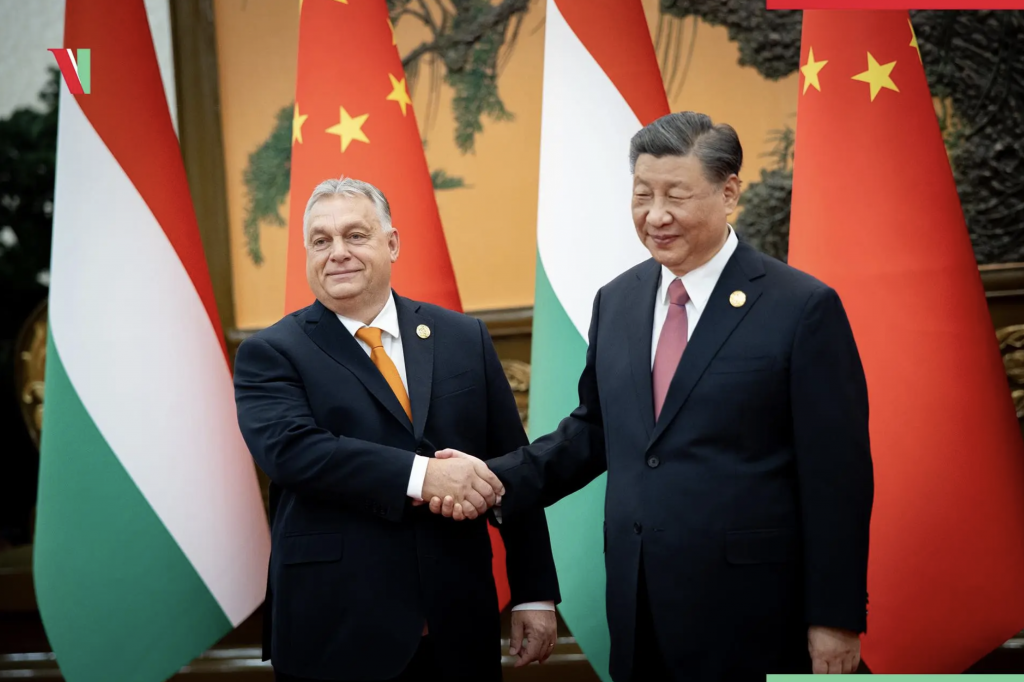

It may be noted that during the pandemic, Budapest became Europe’s largest buyer of Chinese breathing apparatus, masks and vaccines. But Hungary’s bet on China could play a cruel joke on the country, and it’s not just Beijing’s economic problems that threaten its foreign investments. The key issue is that the country is worsening relations with the EU and the US by relying on Chinese money. Another vital trend that worries the West is political. In October 2023, Viktor Orban became the only European leader to visit China as part of the Belt and Road Forum, where he met with Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin. Some saw Orbán’s friendly meeting with a man wanted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes as an insult. Luxembourg Prime Minister Xavier Bettel even said that with this, Orban showed “the middle finger to all the soldiers, all the Ukrainians who die every day and who are forced to suffer from Russian attacks.” Others saw this event as a characteristic example of how Orbán approaches government: ideology is perceived primarily as a political tool, but pragmatism prevails.

Despite the new round of tensions with the EU, China’s top diplomat Wang Yi visited Budapest in early 2024 and offered support to Hungary on public security issues, which definitely went beyond trade and investment relations. The security pact with Hungary was a diplomatic victory for China in its standoff with the European Union, and the Central European country’s growing proximity to Beijing has driven a further wedge into the EU’s collective front.

The Hungarian government’s foreign policy strategy is not difficult to understand: it is a realism in which Orbán wants to maximise the benefits of the relationship in both directions – despite increasingly clear signs that this is not possible in the current geopolitical reality. The Hungarian leadership makes it possible for foreign capital to receive high profits. As long as companies like Audi, Mercedes, Siemens, Deutsche Telekom, Gazprom, Rosatom, Huawei, Wanhua and Sichuan Bohong Group are happy, the Hungarian government can count on a favourable international atmosphere, regardless of the form of government. This is a “peacock dance” in which external support for their “illiberal” system is bought at the expense of the people. Orbán’s connections with the Kremlin and Beijing also fulfil his desire for world-stage recognition.

The influence of the Ukraine factor on internal relations in the EU

Russia’s full-scale aggression against Ukraine has once again raised the level of tension in Hungary’s relations with the European Union. Orban sees the importance of Ukraine to the EU. Therefore, he uses the “Ukrainian issue” in relations with the European Union, bargaining for receiving money from EU funds. Amidst the noise of scandals with Ukraine, Orban also seeks to deal with Brussels for something more to implement his political priorities, voiced during the election campaign. In particular, the abolition of the quota for accepting migrants from Hungary or obtaining additional funding for their settlement. The essence of Orban’s anti-Ukrainian rhetoric is not personal revenge against Ukraine; it is just business. His power is maintained by Russian money, oil and gas. Hungary depends on Russia for 85% of gas supplies, 65% for oil supplies, and 100% for nuclear fuel supplies. The company “Mol”, controlled by him, works on the Russian oil “Urals” and provides excess profits to finance the ruling Fidesz party.

Orban’s current position in Ukraine had a bad background. Relations between the two countries began to deteriorate in the spring of 2014, when, amid the annexation of Crimea and the ATO in Donbas, Orban demanded autonomy for the Hungarians of Transcarpathia. In 2017, Ukraine adopted the Law “On Education”, providing for education in Ukrainian from the fifth grade for national minorities. In 2019, the law on the state language came into force, assigning Ukrainian the status of the only state language in the country. This affected the interests of more than 150 thousand ethnic Hungarians in Transcarpathia. Hungary tried to put pressure on Ukraine and began to impede its relations with the EU and NATO. Hungarian pressure was not strong enough to force the Ukrainians to change their policy. Ukraine was not ready for a compromise, but Budapest did not give up either. The relationship has reached a dead end.

Then Russia invaded Ukraine. Officially, Hungary condemned Russia’s aggression. “Together with our allies in the European Union and NATO, we condemn Russia’s military attack,” Orban said on February 24 in a video posted on his Facebook page. At the same time, it emphasises that the Hungarian government should first think about the safety of the citizens of its country. Therefore, from the very beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Hungarian government spoke out against Western sanctions against Moscow, although Budapest unquestioningly supported all the first sanctions packages.

Orban repeatedly criticises arms supplies to Ukraine, arguing that the war is not ending because of this. Budapest not only does not provide weapons to Kyiv but also does not allow supplies from other EU countries to pass through its territory. Like other European countries, after the Russian invasion, Hungary agreed to accept Ukrainian refugees (unlike people from the Middle East who sought refuge in the country in 2015, the authorities call Ukrainians that way, and not migrants). Help for Ukrainians who fled the war is mainly provided not by the Hungarian authorities but by non-profit organisations and ordinary people. At the same time, unlike many European cities, Ukrainian flags are rarely seen in Budapest – there are none in the parliament building.

The government of Viktor Orban has done everything to ensure that Ukrainians perceive Hungary, if not as hostile, then certainly not as a friendly state. He can unconditionally make an enemy of anyone and anything if it is in his interests: refugees, Brussels, Soros, investors in private pension funds, private entrepreneurs on a single tax. And now Ukraine and the Ukrainian government have become enemies. In Ukraine, they often remember Hungary most positively. Ironically, it was in Budapest in 1994 that Ukraine gave up its nuclear arsenal, and today, Hungary is the main obstacle to European assistance to Ukraine.

At the beginning of December 2022, the conflict between the EU and Hungary reached its peak. Brussels once again sought to freeze funds from pan-European budgets for an EU member. Budapest, in response, used all possible tools to blackmail its colleagues in the European Union, including vetoing the next European package of financial assistance to Ukraine of 18 billion euros. On the eve of the December EU summit, the parties agreed on a big deal: Hungary refused to veto aid to Ukraine and, in return, received 1.25 billion euros from the 7.5 billion initially frozen in pan-European funds. Budapest will be able to obtain the remaining 6.25 billion, only if he carries out reforms that restore the rule of law in Hungary. However, even here, Orban understood the essence of the rule of law in his own way, and on the eve of the EU summit in December 2023, the country adopted a new law “on the protection of sovereignty.” Per his requirements, an exceptional service is being created that will investigate “foreign interference” in the political life of Hungary. The adopted bill has already been compared with the Russian law on “foreign agents.”

The EU summit, which took place in December 2023, was crucial for Ukraine. It discussed starting negotiations on the country’s accession to the EU and allocating the next tranche of financial assistance to Kyiv in the amount of 50 billion euros for the next four years.

After the European Commission recommended that the European Council begin negotiations on Ukraine’s accession to the European Union, Budapest threatened to block them unless Kyiv changed the Education Law. “Hungary’s position is apparent: as long as this law exists, there can be no discussions with Ukrainians about their integration into the EU,” said Balazs, head of the political department of the Prime Minister’s Office. Budapest was also against the EU providing Kyiv with 500 million euros in military assistance and 50 billion euros in macro-financial assistance. At the same time, the government of Viktor Orban unobtrusively hinted that the EU “owes Hungary 3–4–5 billion euros,” and Orban himself pompously assured: “Hungary’s disagreement with the start of negotiations on Ukraine’s membership in the EU is not a subject of bargaining. This cannot be linked to any money issues.”

However, the bargaining turned out to be appropriate. Ukraine has moved to the next stage, bringing it closer to joining the European Union. And the voting itself took place literally without him: on the question of Ukraine, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz invited Viktor Orban to “go out for coffee,” after which the 26 remaining participants in the meeting unanimously voted “for.” However, to make this “historic decision,” Brussels again had to make concessions. Before the summit, the volume of frozen funds intended for Hungary amounted to about 32 billion euros. Although the EU made a lot of efforts to achieve unity in the vote and even unfrozen 10.2 billion euros for Budapest on the eve of the summit, Hungary still vetoed the decision on financial assistance to Ukraine in the amount of 50 billion euros.

It was not possible to reach a compromise on this topic. It looked like this: Budapest was ready to withdraw its objections, but on the condition that the leadership of the European Union unfrozen all the €30 billion that Hungary was entitled to but was once blocked for “bad behaviour.” EU leaders considered this too much and did not give in to “Hungarian blackmail.” In response, Orban slammed the door and blocked the tranche for Ukraine. The issue was postponed until the next summit, which took place in February 2024. What happened in Brussels shocked many Europeans. Thus, the French Le Figaro quotes a European diplomat who believes: “This is a very bad calculation and a terrible signal.” And then another diplomat: “Orban will return to Budapest with money and will not move a single step in Ukraine.

In preparation for the extraordinary summit, the critical issue was financial assistance to Ukraine; the EU focused on finding leverage over Orban’s “democracy.” Brussels decided to change tactics in the new year after an unsuccessful attempt to “push” Hungary at the December 2023 summit. Personal connections of some European leaders with the Hungarian prime minister and symbolic concessions were used. On the morning of February 1 – immediately before the start of the summit – an informal meeting took place in which Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, European Council President Charles Michel and Viktor Orban himself took part. It was during this pre-main event meeting that an agreement was reached.

In addition, some symbolic honours were made to Orban. The EU has committed to holding annual discussions on how effectively Ukraine is spending its funds and, if necessary, reviewing the aid package after two years. Orban himself wanted the package to be reviewed annually and for decisions to be made unanimously, which meant he could block it. However, the EU disagreed with this. Finally, Orban said he had received guarantees that “Hungarian funds” would not be sent to Ukraine. As a result, all EU leaders finally agreed to provide Ukraine with financial assistance in the amount of 50 billion euros until 2027. At the same time, it cannot be said that everything went smoothly: European leaders are definitely looking for approaches to solving the “Hungarian” problem.

European leaders have many tools in their hands: financial pressure, political concessions, informal connections, and even the deprivation of Hungary’s voting rights in the European Council. The problem with these approaches is that they don’t work as a strategic solution. At the same time, approval of aid to Ukraine and similar decisions will require voting more than once. In general, the EU cannot always look for a new approach to Orban or any other leader who will block this or that initiative for his reasons.

In reality, the only long-term solution is the reform of the entire EU, which would eliminate the ability of one country to block decision-making. A project for such a reform already exists – it was developed in the European Parliament and has already been voted on. The scheme strengthens the European Parliament, reduces the use of veto power and turns the EU into something similar to a federal state. However, the process of adopting the reform is very long and complex – it will require changes to the fundamental agreements of the EU, and therefore, it is safe to say that it will take at least several years to solve this problem. The issue of supporting Ukraine will arise more than once during this time. At a minimum, it will be necessary to approve new aid packages for Kyiv, approve new sanctions against Russia, and coordinate the remaining stages of Ukraine’s accession to the EU. Each of these decisions will be made with the participation of Viktor Orban.

As long as the Hungarian Prime Minister feels that the European Union is ready to bargain with him, he will not change his domestic policy and will continue to use blackmail tactics on the foreign policy front. He will also wait for Donald Trump’s victory in the US presidential elections and prepare for revenge and the political “occupation” of Brussels in the upcoming elections to the European Parliament.