Back in 2014, when Ukraine faced open aggression from Russia, which annexed Crimea and partially occupied Donbas, a confident anti-Russian front began to form in the geopolitical arena, supporting Ukraine in every possible way. Among such a pro-Ukrainian coalition, one could single out several countries that provide the most active support to Kyiv and its aspirations to change the foreign policy vector.

Undoubtedly, Ukrainian-Georgian relations have become one of the most significant. The tiny South Caucasian country recently experienced all the “advantages” of having a common border with Russia: as a result of hostilities that lasted for a month, Russia sent troops into the territory of Georgia and later recognised the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, as a result of which Georgia de-facto lost 18% of the territories.

Already in 2014, Ukraine was covered by the “Georgian wave”. Georgian restaurants began to open en masse throughout the country, offering their visitors varied Georgian cuisine. Colourful Georgian outfits, songs, national identity and traditions were popularised on par with Ukrainian ones. So what to hide: after Poroshenko came to power, his former classmate and ex-President of Georgia Mikheil Saakashvili brought to the Ukrainian government part of his team of reformers who tried to implement in Ukraine the same strategy that was previously created for Georgian conditions.

So, by the end of 2014, Saakashvili was an adviser to President Poroshenko and was aiming in every possible way for the post of prime minister. Former Minister of Health of Georgia Alexander Kvitashvili and former Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs of Georgia Eka Zguladze received similar positions in the Cabinet of Ministers. Also, the Ukrainian government was advised by the former Prosecutor General and ex-Minister of Justice of Georgia Zurab Adeishvili, who, in April of the same year, was excluded from the list of persons wanted by Interpol. Economic reforms in Ukraine were carried out with the active assistance of the ex-Minister of the Economy of Georgia, Kakha Bendukidze. In addition to the names mentioned above, many Georgian ex-officials and entrepreneurs flooded Ukraine, forming a whole caste of “untouchable” reformers.

Eight years later, after the mass “Georgianization” of Ukrainian politics, Russia launched a full-scale war against Ukraine, as a result of which international support for Kyiv has increased significantly. At the same time, the list of Ukraine’s closest friends has noticeably changed, and Georgia certainly does not claim leadership positions in it.

In this article, Ascolta analyses Ukrainian-Georgian relations in an attempt to trace how a passionate friendship turned into a cold silence, accompanied by an unwillingness to notice the full scale of Russian aggression against Ukraine for fear of becoming a “party to the conflict” in fact creating a precedent in doing so to justify Russian actions.

Ukrainian-Georgian relations: historical aspect

Relations between the two states began to be built long before the collapse of the Soviet Union and the independence of both Georgia and Ukraine. The geographical location of the territories of the two states contributed to the development of trade relations. Historical references testify to trade between the ancient Georgian kingdom of Colchis and the ancient Greek policies in the northern Black Sea region, carried out as early as the XII century BC.

Speaking about the less distant past, it is worth noting close cultural ties: in the XVIII century, the famous Georgian poet David Guramishvili lived for a long time in the area of Poltava, where he died and was buried (the Guramishvili house museum in Myrhorod is still preserved), and the Ukrainian poetess Lesya Ukrainka moved to Tbilisi for a year in 1904. Her house is still preserved, and a street was named after the poetess (Lesya Ukrainka died in 1913 in the Georgian city of Surami). In 2007, the mutual opening of monuments took place: in March, the Taras Shevchenko’s one in Tbilisi and in May, Shota Rustaveli’s in Kyiv. In 2012, a translation of Ivan Kotlyarevsky’s poem “Aeneid” was published in Georgian. Additionally, many well-known Georgian militaries and politicians were associated with Ukraine throughout the XX century (General Zurab Natiev, Ivan Lordkipanidze, David Vacheishvili and others). Mikhail Grushevsky also spent his childhood and youth in Tbilisi.

Immediately after gaining independence, both states began economic and diplomatic relations that have developed over the past 30 years. In parallel, there was an increase in trade between the two countries. In 1999, the first agreements on the purchase of weapons were signed between Georgia and Ukraine. After 2005, this cooperation intensified at the initiative of Georgia, which increased purchases of various weapons against the background of the aggravation of the situation in South Ossetia.

Ukrainian-Georgian relations: political aspect

By 2012, Ukraine entered the top three of Georgia’s main trading partners. In the same year, seven visits of the top leadership of Georgia to Ukraine were made (in November, Mikhail Saakashvili flew to Kyiv to meet with Viktor Yanukovych).

After Petro Poroshenko came to power, several Georgian politicians, who were members of the inner circle of the ex-president of Georgia, arrived in Ukraine. Two factors caused this situation at once. Firstly, Bidzina Ivanishvili’s Georgian Dream-Democratic Georgia party won the 2012 parliamentary elections, while Saakashvili’s United National Movement party was forced to go into opposition. Almost immediately, an investigation into cases of torture in Georgian prisons was initiated, including reopening an investigation into the death of Georgian Prime Minister Zurab Zhvania (Mikhail Saakashvili was accused of being involved). Secondly, in October 2013, the second term of Saakashvili’s presidency expired. True, without waiting for the official date of completion of his term, he fled to Brussels and later moved to the United States, where he taught for some time.

In 2015, Poroshenko appointed his longtime friend and classmate (they studied together at the Kyiv Institute of International Relations (KIMO), though at different faculties) as head of the Odesa Regional State Administration. However, in 2016, Saakashvili resigned and succumbed to harsh criticism for the failure of all regional reforms. A year later, Saakashvili fiercely opposed Poroshenko, starting to make sharp accusations against him. In July of the same year, Poroshenko signed a decree depriving Saakashvili of Ukrainian citizenship, which was granted to him by a presidential decree in 2014. In 2018 he was deported to Poland. He returned to Ukraine after the victory in the elections of Vladimir Zelensky.

It is important to note that the Georgian authorities regularly criticised the active work of Georgian functionaries in Ukrainian politics. As of 2014, several criminal cases were opened in Georgia against Saakashvili, including:

- Abuse of power in connection with the January 2006 murder of bank clerk Sandro Girgvliani. Girgvliani, 28, was found dead on the outskirts of Tbilisi after an argument with senior Interior Ministry officials in a restaurant. Four employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs were convicted in this case, but two years later, they were pardoned by the president. The investigation believes that Saakashvili’s pardon was part of a preliminary conspiracy with the criminals.

- Abuse of authority during the dispersal of the rally on November 7, 2007, and the destruction of the Imedi television company.

- Abuse of power in connection with the beating of opposition deputy Valery Gelashvili. The attackers wore masks, and an investigation conducted under Saakashvili’s rule found no perpetrators.

- Waste of budgetary funds, so-called “jacket case”. The first details of this case, which became public, concerned the purchase of six jackets for the president at the state’s expense and lunch at a sushi bar. Later, vacations at state expense in fashionable hotels, visits to cosmetic clinics, massages and buying clothes were added to the matter. In general, the amount of embezzlement amounted to 8.8 million lari [about USD 3.3 million].

Of course, it is worth noting that in the cases in which Saakashvili was convicted, there is no direct evidence of his guilt. Still, at the same time, the dissatisfaction of the Georgian authorities accusing Ukraine of refusing to extradite Georgian criminals is quite understandable.

Moreover, as can be understood from the conflict between Poroshenko and Saakashvili, which occurred just two years after the granting of citizenship to the former president of Georgia, it can be assumed that Poroshenko was not very happy with such an undertaking either.

It is worth noting that according to Ascolta, the “Georgian landing” was once imposed on Poroshenko by Victoria Nuland (at that time – Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs) and Joe Biden (at that time – Vice President of the United States). Allegedly, they initiated a new stage in Saakashvili’s career, which allowed him to avoid extradition to Georgia (according to the well-known American principium, “he may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch”).

Georgian 2008 crisis: Ukrainian assistance

In 2008, Ukraine actively supported Georgia during the Russian aggression. Moreover, Russia has filed official accusations against Kyiv because of the alleged presence of data on the ongoing supply of Ukrainian weapons to Georgia, which were carried out after the start of the conflict in South Ossetia. In connection with such statements, a temporary investigative commission was created in the Ukrainian parliament to study the legality of arms sales to Georgia (headed by Valery Konovalyuk).

At the same time, according to Ascolta, in 2007-2008, the Ukrainian state enterprise Ukrspetsexport supplied Georgia with six self-propelled firing systems 9A310, three service vehicles 9V881E and three transport vehicles. We are talking about the supply of air defence systems “Buk”. Moreover, all deliveries were made before August 2008.

Moreover, even before the start of hostilities in Georgia, Ukrainian instructors conducted air defence training for the Georgian military, which also resulted during the Russian aggression in 2008.

Despite the fact that active attempts by the Russian side to accuse Ukraine of supplying weapons and military equipment to Georgia after the start of the conflict, as well as the participation of Ukrainian mercenaries and air defence crews on the Georgian side, no reliable data or direct evidence have been provided.

Internal political system of Georgia: neutrality or return to Russia

Over the past 15 years, Georgia has faced a number of political crises caused both by an attempt to change the foreign policy vector and by the struggle of internal clans for power. Due to its geographical location, the small country of the South Caucasus is an important regional player influencing the situation in the region. In this case, several parallels can be drawn with Ukraine, which for many years was perceived by Georgia as the closest partner and ally in its aspirations to join the EU and NATO.

After the 2008 war, Georgia announced several fundamental reforms, the implementation of which was supposed to demonstrate to the entire Western world Tbilisi’s desire for Europe. As a result, foreign media actively relayed stories about the glass offices of state bodies, zero corruption, the eradication of oligarchs and bandits, and most importantly, Georgia’s complete turn from Russia towards the West. True, a few years later, Saakashvili significantly softened his anti-Russian policy and was forced to make many compromises. In particular, in 2012, he signed a decree abolishing visas for Russians. As a result, Russian citizens could freely enter the territory of Georgia and stay there without a visa for 90 days.

In 2011, an oligarch of Georgian origin, Bidzina Ivanishvili (also commonly known as Boris Ivanishvili), appeared in the domestic political arena of Georgia. He declares his opposition to Saakashvili and defines the primary goal of preventing the current government from usurping all political processes. Ivanishvili also created the Georgian Dream – Democratic Georgia party, which won the 2012 parliamentary elections and formed a majority in Parliament. As a result, Ivanishvili himself receives the post of prime minister. After taking office, Ivanishvili gradually reduced Saakashvili’s influence, concentrating the main political tools in his hands.

Ivanishvili described his political position as neutral concerning all external players. For example, immediately after winning the parliamentary elections, he stated that the United States is Georgia’s leading strategic partner and friend. At the same time, already next year, during a forum in Davos, he held talks with Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and later announced his desire to meet with Putin. Ivanishvili tried to maintain a similar political balance throughout his political career, calling Georgia’s European integration a key priority. At the same time, the opposition media criticised him for being too pro-Russian, often quite justified.

In 2018, Salome Zurabishvili won the presidential election. Even though she was nominated as an independent candidate, Ivanishvili’s party, “Georgian Dream – Democratic Georgia”, made no secret of its support for Zurabishvili. Zurabishvili’s main competitor was Grigol Vashadze, a candidate from Saakashvili’s United National Movement party.

Moreover, Ivanishvili and Zurabishvili have many things in common in their biographies. At a minimum, both lived in France for a long time. Moreover, from 2003-2005, Zurabishvili was France’s Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Georgia. Finally, according to Ascolta, it was Zurabishvili who helped Ivanishvili obtain Georgian citizenship in 2004 (at that time, he was a citizen of France and Russia).

Although in 2021, Bidzina Ivanishvili announced his retirement from politics (officially due to his age), the political system of Georgia continues to be associated with his name.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine: Georgian “neutrality”

On February 24, 2022, most UN member states unequivocally condemned Russia’s actions against Ukraine and called on Putin to immediately stop military aggression against the civilian population. Belarus, Venezuela, Iran, Nicaragua, Myanmar and Syria were among those who supported Russia’s actions. As for Georgia, on the one hand, it voted for UN General Assembly resolution ES-11/1 condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (in fact, it supported several subsequent resolutions on Ukraine). But on the other hand, Georgia refused to provide any military assistance to Ukraine, impose any sanctions against Russia, and cancel the visa-free regime for Russian citizens.

Moreover, in early March, the leader of a group of Georgian volunteers, the head of the Anti-Occupation Movement of Georgia, David Katsarava, said that local authorities did not permit the plane to land, which was supposed to take them to Poland, from where they planned to go to war in Ukraine. According to open data, about 1,500 Georgians are currently fighting in Ukraine, many of whom are members of the “Georgian Legion”, created during the ATO.

The position of Georgia concerning Russian citizens (primarily men of military age), who fled en masse to the country after the announcement of partial mobilisation in October 2022, has become very indicative. According to Salome Zurabishvili, about 700,000 Russian men fled to Georgia as of mid-November, 600,000 of whom later left for European countries, Turkey or Armenia. Despite the appeals of Ukraine and several European states, Georgia did not close its borders to Russian citizens. At the same time, such “migration” has brought its fruits to Georgia. So, in December 2022 alone, Georgia received $535.5 million from abroad in December, 317 million of which were transferred from the Russian Federation. Also, over eight months of 2022, more than 12 thousand citizens of the Russian Federation purchased over 15 thousand buildings and structures in Georgia.

At the same time, in December 2022, another scandal broke out in relations between Ukraine and Georgia: Andriy Kasyanov, Chargé d’Affaires of Ukraine in Georgia, claims that Tbilisi has been ignoring Kyiv’s requests for help in supplying generators for a month now in the energy crisis after Russian shelling. In response, Mamuka Mdinaradze, head of the faction of the ruling Georgian Dream party, said that he had heard for the first time about the request of the Ukrainian side for the supply of generators and transformers. It is worth noting that as of January 2023, Georgia transferred to Ukraine about 25 industrial generators and about 470 domestic ones.

For objectivity, it should be noted that as of December 2022, Georgia has donated over $12 million worth of humanitarian aid. Also, about 25,000 Ukrainian refugees are on its territory, many of whom can use public transport for free and receive a daily allowance of $16.

Military assistance is the main stumbling block

But still, the most acute issue concerning the two states was the issue of providing certain types of weapons, which Georgia once received from Ukraine. Firstly, we are talking about the “Buk” anti-aircraft missile system.

This issue has already caused heated discussions, which once again called into question the pro-European position of Georgia and its desire to join the anti-Russian position.

On Tuesday, January 10, the Ministry of Defense of Georgia issued an official statement in which it refused to transfer the Buk air defence system and the Javelin anti-tank systems to Ukraine. The Georgian side explained the reason for the refusal by the fact that the information about the Buk air defence system transfer from Ukraine to Georgia in 2007 is untrue and, in fact, the Georgian side bought these systems under a secret contract. Also, in 2017, Georgia spent tens of millions of dollars on purchasing American Javelin anti-tank systems.

After active criticism of this position, the Georgian authorities tried to give a few more explanations. For example, they made a statement that the “Buk” air defence systems transferred by Ukraine were faulty back in 2008, respectively, after 13 years, they definitely cannot be used.

At the same time, the Georgian media began to actively debate the information that the transfer of such weapons to Ukraine would lead to a critical situation in the army and will expose the Georgian air defence system.

Moreover, the Georgian side has repeatedly argued its unwillingness to transfer any weapons to Ukraine for fear of being called a “party to the conflict”, which allegedly could lead to “the opening of another front of hostilities” – that is, a Russian attack on Georgia.

It is noteworthy that each argument contradicts the others, but no matter how strange it may look, each of them was voiced with a difference of several days.

Myths and reality

An analysis of the Georgian position regarding Ukraine and Russian aggression demonstrates the presence of several myths that have all the signs of a purposeful dissemination of certain theses to form the necessary public opinion. Of course, Ascolta does not make any accusations against Georgia, realising that in addition to economic and political interests, there may be a real threat of military aggression (we have a common neighbour and understand everything). Moreover, the experience of such aggression in 2008 forces us to carefully weigh the pros and cons when making such decisions.

But at the same time, our team offers its vision of the situation, which is entirely subjective, but still can help dispel a few myths:

Myth 1: The transfer of such weapons will make Georgia a party to the conflict.

It is important to note that since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Western coalition formed to support Ukraine has been regularly transferring various types of weapons to Kyiv, among which you can find more lethal specimens than the Buk air defence system. Moreover, back in April 2022, Slovakia handed over another Soviet-style air defence system to Ukraine: the S-300 air defence system. In general, the last Ramstein (international conference on military assistance to Ukraine) demonstrated that the transfer of the Buk air defence system is unlikely to become more dangerous than the “tank tranche” from Germany, the United States and Great Britain.

In any case, almost every agreement on the supply of new types of weapons to Ukraine was accompanied by statements by the Russian side about the most severe retaliatory measures, which, apparently, consist of the publication of new interviews of Dmitry Medvedev with a set of eloquent phrases addressed to the West.

Myth 2. The Buks provided by Ukraine were faulty.

The “Buk” air defence systems were so faulty that during the 2008 Five-Day War, at least six Russian combat aircraft were shot down by Georgian air defence, including one long-range Tu-22M3 bomber.

Of course, it can be assumed that over 13 years of operation, certain parts or systems could wear out. But it is not worth saying that Ukraine transferred the system in this form. Moreover, according to the Georgian side, the “Buk” air defence systems were bought, and to announce the purchase of faulty weapons was to sign of corruption.

Myth 3. The transfer of air defence systems to Ukraine will expose Georgia’s air defence system.

In this case, we will turn to both Georgian and Russian sources of information so that neither one nor the other accuses us of manipulation.

It is worth noting that after the military reform of Georgia in 2009, the provision of air defence was entrusted to the Georgian Air Force, reassigned to the ground forces as an aviation component.

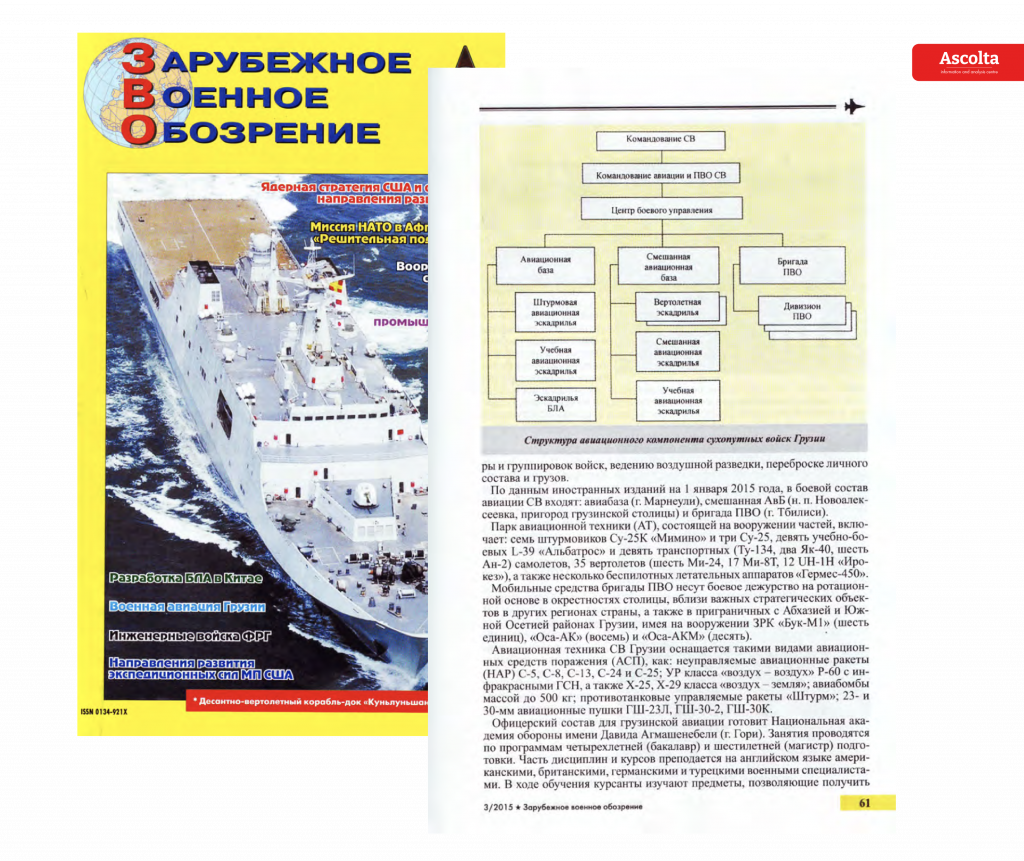

The air defence brigade (Tbilisi), which is part of this type of troops of Georgia, according to Russian data (the magazine “Foreign military review”, issue No. 3 of 2015, p. 61), only in 2015 was armed with six units. SAM “BUK M-1”, 8 units. SAM “Osa-AK” and 10 units. SAM “Osa-AKM”.

According to Ascolta, in 2007-2008, the Ukrainian SE “Ukrspetsexport” delivered the following equipment to Georgia in total:

– self-propelled artillery (SPA) 9A310 – 6 units;

– service vehicles (SV) 9V881E – 3 units;

– transport vehicles (TV) 9T229 – 3 units.

As a result of the fighting in 2008, 2 SOU, 2 AO and 2 TM were captured by Russian troops. Accordingly, Georgia has four units of Ukrainian self-propelled firing systems 9A310, service vehicles and transport vehicles – one unit each. According to Russian experts, Georgia began to restore air defence systems after the war by purchasing complexes in Israel, France, and Ukraine (Foreign Military Review magazine, issue No. 12, 2020, p. 82). After the signing on September 11, 2020, of an agreement on the modernisation of air defence between the Ministry of Defense of Georgia and the Israeli company Rafael Advanced Defense Systems, the reform of this type of troops reached a higher level of development, which caused some concern for the Russian military.

Based on this, it can be noted that the transfer of six pieces of equipment to Ukraine will not significantly affect the combat capability of the Georgian air defence component.

Conclusions and forecasts

Actively produced in an attempt to hide the true reason for the reluctance to transfer weapons to Ukraine, the arguments themselves demonstrate the presence of more serious reasons that make us once again analyse the “friendly” relations between the two countries.

Despite its “neutral” position, Georgia, as before, does not give up its ambitions to join the EU and NATO. Moreover, taking advantage of the wave of support for Ukraine’s European integration intentions, Georgia also applied for the status of a European Union member candidate. It is remarkable that Georgian Prime Minister Garibashvili even stated that his country deserved this status more than Ukraine and Moldova. However, unlike Ukraine and Moldova, Georgia was not given this status. On the other hand, this factor may help Tbilisi to maintain its neutrality in the future.